“After the Rebellion” — Hank Whittemore at the Shakespearean Authorship Trust (S.A.T.) conference at Shakespeare’s Globe – November 2019

Published in:

on March 11, 2020 at 6:57 pm

Comments (2)

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, Venus and Adonis, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, Venus and Adonis, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

After the Rebellion: “Shakespeare’s” Final Tragedy and His Triumphant Rebirth

[Following is my talk at the Shakespearean Authorship Trust (S.A.T.) conference at Shakespeare’s Globe in London on 24 November 2019. The text has been adjusted for print and slightly expanded for greater clarity.]

Some years ago, I was on a train heading down to New York City and found myself sitting next to a distinguished looking gentleman who turned out to be an architect who also loved literature and drama. We began talking and he asked me about myself and, at some point, I mentioned I’m one of those folks looking for the “real” Shakespeare. He turned and looked at me with intensity and put up his finger, and I flinched. Who knows what this topic is going to bring out in people!

“Look,” he said, “there are two things you have to know about Shakespeare, whoever he was. One, he uses words to stimulate the muscle of your visual cortex, so it throws images on the screen of your mind.” He mentioned some examples, such as Horatio in Hamlet describing the dawn as a knight in rusted armour, climbing up “o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill.”

“The second thing you need to know,” he said, “is that Shakespeare is a storyteller. And his greatest stories are tragic. Therefore, just identifying the real author will not be good enough. What you need to do is find that tragic story.”

We talked a lot more … the authorship question was new for him and he thought the whole idea of this mystery must be deeply sad and tragic. He was thinking about how this great author’s identity could have been obliterated. He considered it would have been a form of murder, or suicide, in the face of some powerful force against him.

Well, as many of you know, I’m convinced the true voice of the author is that of Edward de Vere, Lord Oxford, and that he provided the unifying vision of the individual artist that we know as “Shakespeare.” And, too, that it’s in the Sonnets where we find his most directly personal voice.

Oxford’s death or disappearance in June 1604 was followed soon upon by publication of the full-length second quarto of Hamlet; and in that great tragedy, the protagonist, the most autobiographical of all Shakespearean characters, cries out to his friend: “O God, Horatio, what a wounded name! Things standing thus unknown shall I leave behind me!” Then he begs Horatio to “tell my story” — his tragic story that remains unknown to the world; and that sounds like what my friend on the train was talking about.

Well, the focus of our gathering here at Shakespeare’s Globe is the failed Essex Rebellion led by the earls of Essex and Southampton – an event which, I submit, is the inciting incident of the tragic story of the Shakespearean author’s posthumous loss of identity. In this view the rebellion is not the end of the story, but, rather, the beginning of de Vere’s final evaporation behind the pen name; and this perspective sheds light on a crucial legal story that I want to share with you.

I also hope to show that Oxford countered this loss of identity with a super-human effort to create, in the Sonnets, his final masterwork – to preserve his final story and prevail in death, thereby creating his own resurrection and ultimate triumph.

This final story takes place during the two years and two months following the failure of the so-called rebellion — a period which, I suggest, is the true historical time frame and all-important context for Oxford’s posthumous disappearance as the author. This was a dark time when Southampton languished in the Tower as a convicted traitor; when the condemned Earl of Essex wrote a long poem to Queen Elizabeth from his prison room, during the four days before his execution; and when Southampton also wrote a long poem to her Majesty from his Tower room, begging for mercy – a poem discovered less than a decade ago. (“Was Southampton a Poet? A Verse Letter to Queen Elizabeth” by Lara M. Crowley, English Literary Renaissance, 2011.)

I agree with Ms. Crowley that these poems by the earls are more accurately called “verse letters” of communication with the queen; and clearly the Sonnets are verse letters as well.

First the prologue: the Shakespeare pseudonym making its grand entrance just eight years before the rebellion, in 1593, when things are heating up to determine control of succession to Elizabeth – who, by refusing to name anyone, is putting the country in danger of civil war around the throne when she dies. The Essex faction is up against the entrenched power of William Cecil Lord Burghley and his rapidly rising son Robert Cecil, the cunning hunchback seething with resentment toward those nobles whom he views as so unfairly fortunate by their birth alone. The goal of the Essex faction is to prevent the Cecils from continuing their power into the next reign; but I don’t need to tell you that Robert Cecil is going to win this game. He is going to outwit and outmaneuver those spoiled, arrogant noblemen.

(Consider this strikingly blunt comment about Robert Cecil from the Dictionary of National Biography 1885-1900: “Life was to him a game which he was playing for high stakes, and men and women were only pieces upon the board, set there to be swept off by one side or the other or allowed to stand so long only as the risk of letting them remain there was not too great.”)

Now in 1593 the previously unknown author William Shakespeare (without any prior history of written work) suddenly appears on the dedication of Venus and Adonis to Southampton. “Shakespeare” is on the side of those same young lords heading toward their tragic end game, which is also the end game to determine the future course of England.

A year later, in the 1594 dedication of Lucrece to Southampton, the same author confirms where he stands with an extraordinary public promise: “The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end …What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours.” This from a great author with a vast storehouse of 25,000 words from which he can choose, who never needs to repeat any word twice, much less three times in a single sentence.

It’s a pen name, saying, in effect: “All the writings I have done so far (i.e., the two narrative poems), and all the writings I am going to do in the future, published under this name, are for you and in your support. These written works are, and will be, yours … yours … yours.”

Once Burghley dies in 1598 and Principal Secretary Cecil takes over, the gloves come off with the first issuance of plays under the pseudonym, among them Richard III with “Shake-speare” hyphenated as if to emphasize the image of a writer “shaking the spear” of his pen. This play of royal history contains a mirror image of the hunchbacked Cecil, an allegorical portrait of him as an evil monster, and a shockingly obvious attack on him that the secretary cannot, will not, ever forgive. He will bide his time, keeping a steady course, until he gets revenge.

In the next year, 1599, it appears that “Shakespeare” in the chorus of Henry V is publicly cheering for Essex’s success on the Irish military campaign, in which Southampton is also a leader. The playwright predicts that “the general of our gracious Empress” will return with “rebellion broached on his sword,” but the effort to crush the revolt is doomed – in no small part because Cecil has prevented the earls from receiving the needed assistance.

That fall back in London, Essex is in deep trouble with the queen and her council, under Cecil’s pressure against him. Meanwhile Southampton spends much of his time attending politically instructive plays at the Curtain such as Julius Caesar by “Shakespeare,” who, for the public audience, is creating an allegorical road map toward avoiding civil war and achieving a peaceful royal succession.

Events are moving fast, tensions are building, as the aging queen falls increasingly under Cecil’s influence. In January 1601 Southampton is attacked in the street by Lord Gray and his party on behalf of Cecil and Raleigh; the earl draws his sword and fights them off with the help of his houseboy, who joins in the fray and has one of his hands lopped off. As far as Essex and Southampton are concerned, they are in mortal danger and can no longer delay taking action.

In the first week of February, Southampton takes charge of planning to finally gain access to the queen at Whitehall. They plot to hold Cecil captive so Essex and Southampton can be in her Majesty’s presence and convince her to call a Parliament on succession – to finally name someone, even give up her crown, avoid civil war, and remove Cecil in the bargain.

Preparing for this confrontation with the queen, the conspirators on Sunday 7 February 1601 attend a special performance of Richard II with a deposition scene of the king handing over his crown. In this newly revised play, Oxford demonstrates to the Essex faction how it might be possible to confront Elizabeth with rational arguments and persuade her to do the same – without, most importantly, violating the laws of God or man.

Of course, the play is viewed allegorically, making it easy for Cecil to incite the queen’s fear and anger; and Elizabeth well understood, as she later exclaimed: “I am Richard Second, know ye not that!”

More immediately, however, the cunning Cecil uses this special performance to summon Essex to the palace that night for questioning; and his calculated move predictably causes the earl to panic. The next morning, at Essex House, his followers are clamoring in the courtyard amid an atmosphere of chaos. The subsequent events predictably end in disaster; that night, both Essex and Southampton surrender up their swords and are taken through Traitors Gate into the Tower of London, facing charges of high treason against the crown and virtually certain execution.

Eleven days later, at their joint trial in Westminster Hall, are two of the future leading candidates for the authorship of the “Shakespeare” works: Sir Francis Bacon, viciously prosecuting; and Lord Oxford, having come out of retirement to sit as highest ranking earl on the tribunal of peers sitting in judgment. The accused earls will both be found guilty and sentenced to death; Essex will be executed six days later, but Southampton will find himself in perpetual confinement.

Now all authorized publications of as-yet-unprinted Shakespeare plays have abruptly ceased; aside from the full Hamlet in 1604, there will be no more newly printed authorized plays for nearly two decades; but my theme here is that the rebellion is not the end of author’s tragic story, it’s the beginning.

In the normal telling it’s the conclusion: Southampton remains in the Tower while Cecil, under terrible tension, works desperately and even treasonously to communicate in secret with King James in Scotland. In that traditional history, Shakespeare writes few if any sonnets to Southampton all during the twenty-six months of his imprisonment. Then, upon Henry Wriothesley’s release from the Tower by King James on 10 April 1603, the author suddenly exclaims in Sonnet 107 that “my true love” had been “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom” but is now free; and, therefore, “my love looks fresh” – once again, offering the young earl his endless love, devotion and commitment.

Was Shakespeare a hypocrite? His true love in the prison and he writes maybe a few private sonnets to or about him, or none at all, only to jump back on the bandwagon when Southampton is liberated? Well, I don’t think he could have been hypocritical.

Thinking about my friend on the train describing Shakespeare as a masterful storyteller, I recall the diagram of the most basic structure of a story, the way my English teacher drew it on the blackboard. In that light, if Sonnet 107 at the climax celebrates Southampton getting out of the Tower, in 1603, how could we care about that event unless the author has already established when he was put in the Tower two years earlier, back in 1601? In the framework of such a story, certainly Southampton’s entrance into the prison fortress is the inciting incident that finally reaches the climactic turning point later, in 1603.

Why would we care about Southampton getting out of the Tower if we didn’t know, in the first place, that he was in there? Well, if we climb back down the consecutively numbered sonnets, we can see that the usual view is wrong. A journey “back down the ladder” of sonnets takes us through a long series of darkness, despair, prison, trial, legal words related to crime, guilt, death – all the way back down to where this great wave of darkness and suffering first appears; and then it becomes clear that literally dozens and dozens of sonnets have been leading up to the climax.

The author did not abandon Southampton; he never stopped writing to or about him; and in this context – the context of the prison years – those legal words are no longer metaphorical; rather, they are real, and carefully accurate: real words applied to real life, when the author is steeling himself against the worst outcome for the young earl.

Now I hope you’ll to indulge me for less than ninety seconds, as we take a quick “fly-over” to view these words from the high point of Sonnet 107 back downward; and this is just a sampling of those dark and legal words as we climb back down to where they begin at Sonnet 27:

(Sonnets 106-96): Confined doom, Wasted time, weak, mournful, despair, death, dark days, decease, fault;

(Sonnets 92-87): Term of life, thy revolt, sorrow, woe, fault, offence, night, attainted, misprision, judgment;

(Sonnets 86-77): Tomb, dead, confine, immured, attaint, decayed, waste, graves; (74-66): Fell arrest, bail, death, buried, blamed, suspect, died, dead, for restful death I cry;

(Sonnets 65-57): Plea, gates of steel, drained his blood, shadows, for thee watch I, imprisoned, pardon, crime, watch the clock for you;

(Sonnets 55-51): Death, judgment, die, deaths, shadows, shadow, up-locked, imprisoned, offence, excuse;

(Sonnets 50-46): Heavy, bloody, grief, lawful reasons, allege, bars, locked up, thyself away, defendant, plea deny, verdict;

(Sonnets 43-38): Shadow, grief, waiting, blame, forgive, grief, absence, torment, pain;

(Sonnets 37-33): Shadow, confess, guilt, trespass, fault, lawful plea, offender’s sorrow, ransom, basest clouds;

(Sonnets 32-27): If thou survive, dead, grieve, buried, death’s dateless night, disgrace, outcast, hung in ghastly night…

That’s just a sampling of the “dark” words and legal terminology in the eighty sonnets from the climax of Sonnet 107 all the way back down to number 27, in which the author tries to sleep that night in the darkness, but his mind travels instead to Southampton in the Tower. He can imagine the earl up there in a window, like “a jewel hung in ghastly night.” In the dictionary “ghastly” is “frightful, dreadful, horrible,” as in “a ghastly murder” – or, we can be sure, like the ghastly torture of being hanged, drawn and quartered.

SONNET 27 on the night of the failed Rebellion on the Eighth of February 1601, where the story begins:

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travail tired.

But then begins a journey in my head,

To work my mind, when body’s work’s expired.

For then my thoughts (from far where I abide),

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness, which the blind do see.

Save that my soul’s imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which like a jewel (hung in ghastly night)

Makes black night beauteous and her old face new.

Lo thus by day my limbs, by night my mind,

For thee, and for myself, no quiet find.

Southampton entering the Tower as a prisoner is the first of many recorded, factual events. The overall circumstance is that he’s accused of a crime; and sure enough, in this diary of verse letters, Oxford calls it by name:

“To you it doth belong yourself to pardon of self-doing crime” – Sonnet 58

“How much I suffered in your crime.” – Sonnet 120

In this case, the crime is that of treason, the most serious offence Southampton could have committed. It would almost cost him his life and cause the author of the Sonnets to descend into darkness and despair and finally to disappear. So, now, from Sonnet 27 forward, we have what might be called the “foundational tracks” of his personal story. These tracks during Southampton’s more than two years in prison are on the record; Oxford knows they are events that will be indelibly stamped upon English history.

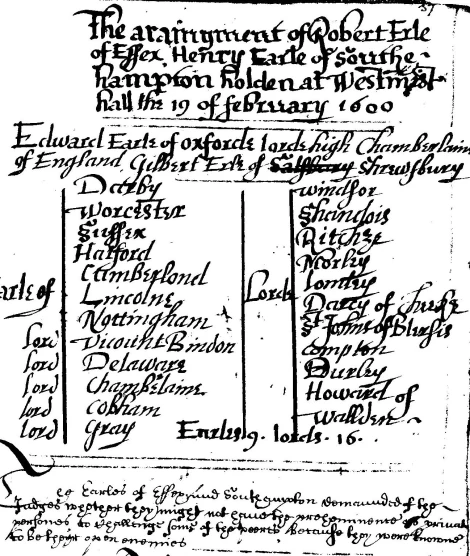

Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford served as highest-ranking nobleman on the tribunal at the February 19, 1601 treason trial of Essex and Southampton — as indicated by a contemporary notice of the event

FEBRUARY 11, 1601: The twenty-five peers, Oxford among them, are “summoned” to serve on the tribunal at the “sessions” or treason trial; and in Sonnet 30 the author writes: “When to the Sessions of sweet silent thought, I summon up remembrance of things past.” Yes, it’s poetry, but I suggest there’s a “second intention,” which is actually the primary context – and, as you have probably noticed, that’s the most important word of this talk: context.

FEBRUARY 19, 1601: The trial of Essex and Southampton is held on this day at Westminster Hall. Bacon prosecutes; Oxford sits with the peers, who come to a foregone unanimous conclusion: both earls are found guilty of treason and sentenced to be executed.

Oxford, reacting to the tragedy, addresses Southampton in Sonnet 38 and wonders in sorrow: “How can my Muse want subject to invent/ While thou dost breathe? … The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise.” In Sonnet 46 he glances back at the recent trial: “And by their verdict is determined…”

FEBRUARY 25, 1601: Essex is executed on the Tower Green by beheading; and the poet writes in Sonnet 44, referring to Southampton and himself, about their “heavy tears, badges of either’s woe.”

MARCH 5, 1601: The treason trial of five conspirators; all convicted and condemned to death; and Oxford writes to Southampton in Sonnet 57: “I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you.”

MARCH 13, 1601: Gelly Merrick & Henry Cuffe are hanged, drawn and quartered. “For thee watch I,” Oxford writes to Southampton in Sonnet 61; and in Sonnet 63 he sets down his fears that Wriothesley will face the executioner’s axe – using a double image that combines both universal time/age and specific words such as “knife” and “cut” and “life” related to beheading:

For such a time do I now fortify

Against confounding Age’s cruel knife,

That he shall never cut from memory

My sweet love’s beauty, though my lover’s life.

MARCH 18, 1601: Charles Danvers & Christopher Blount are publicly beheaded, leaving Southampton as the only one with the death sentence hanging over him; and the author writes Sonnet 66 as a virtual suicide note, listing reasons he wishes to die:

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry …

Tired with all these, from these I would be gone,

Save that to die, I leave my love alone.

He would prefer to kill himself, but will not commit suicide while Southampton remains alive and “alone” in the Tower. In that same virtual suicide note, he complains about “strength by limping sway disabled,” and John Dover Wilson (in his Cambridge edition of the Sonnets in 1969) finds it “tempting to suspect a glance at the control of the state by the limping Robert Cecil.” Well, as my friend on the train might say, it’s not only tempting, it “stimulates the muscle of our visual cortex” to create an image of Cecil swaying and limping toward his “disabling” or destruction of the earls.

“And captive good attending Captain Ill,” Oxford adds. Southampton, the captive prisoner, is at the mercy of Captain Ill, echoing Cecil, the captain in command of the situation.

Early the next morning, crowds wait on Tower Hill for the spectacle of Southampton being executed, but they’re disappointed because, without official explanation, the scaffold is taken down. The earl’s life has been spared. His sentence is quietly reduced to perpetual confinement. He becomes a nobody, stripped of all lands and titles, and is now “Mr. Henry Wriothesley,” a commoner, and even “the late earl” – a dead man in the eyes of the law; and therefore, in Sonnet 67: “Ah, wherefore with infection should he live … Why should he live …?” And in Sonnet 69: “Thou dost common grow…”

Is Cecil is holding him hostage in the Tower? If so, the key must be Oxford himself and Cecil’s need to remove all future trace of him as the author calling himself Shakespeare, the poet-dramatist who devoted his work to Southampton, and, too, who had depicted Cecil as the monstrous ruler Richard the Third.

In number 87 of this diary of verse letters, Oxford supplies the legal mechanism by which Southampton’s life was spared:

So thy great gift, upon misprision growing,

Comes home again, on better judgment making

“Misprision of Treason” is literally a “better judgment” or verdict, a reduction of the crime of treason. This special judgment is a kind of plea bargain, used by Tudor monarchs to gain information in exchange for a lesser verdict. It means Southampton was supposedly ignorant of the law; he knew about the plot but didn’t really participate and failed to report it; he expresses true sorrow or repentance; and it gives him the possibility of future liberation and even a royal pardon, so he cannot be retried for the same offence.

Oxford supplies a crucial account of how this better legal judgment for Southampton was obtained. Soon after Sonnet 27 on the night of the failed rebellion, anticipating the trial, he promises Southampton in Sonnet 35 that “Thy adverse party is thy Advocate,” or as editor Katherine Duncan-Jones reads the line: “Your legal opponent is also your legal defender.”

Oxford has no choice but to join the other peers on the tribunal, in effect acting as Southampton’s “adverse party,” forced to vote with them to condemn him to death; but he also vows to work (privately, behind the scenes) as the earl’s “Advocate” or defense attorney, trying to save his life.

He must make a deal with Cecil, his former brother-in-law; and as he records in the Sonnets, there is a kind of prisoner exchange, that is, Oxford offers his life in exchange for Southampton’s reprieve from execution and possible future liberation. The younger earl is in fact spared from execution, without any official word, but he must remain in confinement until the monarch decides to release him and perhaps grant him a pardon.

Oxford instructs him on the law (and the plea deal), adding in Sonnet 58, “To you it doth belong yourself to pardon of self-doing crime,” that is, “Your life is in your own hands, young man.”

The monarch who may give him a pardon, however, will not be Elizabeth, who is much too angry and fearful. Cecil must succeed in bringing James to the English throne; only then will Cecil can he continue in his position of power, and only then might Southampton get out alive. Therefore, to save Southampton, Oxford must agree to help Cecil make James the King of England. (And to that end, perhaps Edward de Vere is the unidentified “40” in the Secretary’s secret correspondence with the Scottish king).

Also in Sonnet 35, Oxford blames himself for “authorizing” the crime as author of Richard II and depicting Elizabeth “with compare” as that historical king; as Duncan-Jones explains, “authorizing” is “used here in a legal sense for sanctioning or justifying, with a further play on ‘author’ as composer or writer.”

All men make faults, and even I in this,

Authorizing thy trespass with compare…

Oxford is guilty not only for writing Richard II with its deposition scene, but, also, for allowing the Chamberlain’s Men to give the special performance of his play that Cecil then used to trigger the whole debacle. The actors are called in for questioning, but not the author, even though he had played a crucial role in the crime. In fact, he himself could possibly be charged with Treason by Words, if the queen chose to believe that Richard II depicts her as a tyrant. Oxford, too, could be executed.

More important to Cecil, however, was being able to ensure that Oxford, his former brother-in-law, could not be linked to the portrait of him in Richard Third (or, for example, that Oxford could not be linked to portraits of Burghley in the quartos of Hamlet). Instead of Oxford himself being physically executed, his identity could be obliterated beyond his death — forever — behind the Shakespeare pen name. Oxford could agree to that (and to ensuring that no one who know the truth will ever reveal it), if it means saving Southampton; and therefore, an essential part of the plea deal is his self-sacrifice.

In Sonnet 35 he records his acceptance of posthumous disappearance: “And ‘gainst myself a lawful plea commence” – a legal plea bargain, directed against himself. At the same time, Southampton must agree to his own guilt and confess that he never meant to commit treason; and so, for example, he writes to the Privy Council from his prison room: “My soul is heavy and troubled for my offences … My heart was free from any pre-meditate treason against my sovereign….”

Oxford refers in Sonnet 34 to the younger earl’s need to repent, while he himself must take on a Christlike role:

Though thou repent yet I have still the loss,

The offender’s sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offence’s cross …

In his poem to the queen, Southampton begs for mercy:

Vouchsafe unto me, and be moved by my groans,

For my tears have already worn these stones.

His tears of repentance are “riches” to be paid, the way other noble prisoners are able to use actual money to purchase their freedom. Oxford reminds him in Sonnet 34 that his tears of repentance are a form of “ransom” for his life and possible liberty:

Ah but those tears are pearl which thy love sheeds (sheds),

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

The price also includes total separation from each other – in life, on the record, in future history. Oxford had linked Southampton to the pen name; the earl and the famous pseudonym went together; therefore, now Oxford must agree to de-link himself from not only “Shakespeare,” but, also, from Southampton. The two of them must be “twain” or apart, one from the other, as Oxford tells Southampton in Sonnet 36:

Let me confess that we two must be twain …

I may not ever-more acknowledge thee…

The author, a legal expert, finds in Sonnet 49 another way to phrase the same legal bargain behind the scenes:

And this my hand against myself uprear,

To guard the lawful reasons on thy part.

To leave poor me, thou hast the strength of laws…

The dark time continues, no one knowing the outcome.

FEBRUARY 8, 1602: First anniversary of the failed Rebellion: Southampton has spent one full year in prison, as Oxford records in Sonnet 97:

How like a winter hath my absence been

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year!

“Fleeting” is a deliberate play on the Fleet Prison to emphasize Southampton’s continuing confinement.

FEBRUARY 8, 1603: Second anniversary, marking two years or “three winters cold” in the Tower as indicated in Sonnet 104, covering the three Februaries of 1601, 1602 and 1603.

MARCH 24, 1603: Queen Elizabeth, the “mortal Moon,” dies in her sleep and those “sad Augurs” who predicted civil war are proved wrong. Cecil quickly proclaims King James of Scotland as James I of England, and the new monarch, who uses “Olives” to symbolize peace, quickly sends ahead the order for Southampton’s release. On April 10, 1603, after all the uncertainties are crowned with assurance, and after Southampton was “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom,” he walks out of the Tower as a free man and Oxford records this amazing climax of his recorded story in Sonnet 107:

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul

Of the wide world dreaming on things to come

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Supposed as forfeit to a confined doom!

The mortal Moon hath her eclipse endured,

And the sad Augurs mock their own presage,

Incertainties now crown themselves assured,

And peace proclaims Olives of endless age.

Now with the drops of this most balmy time,

My love looks fresh, and death to me subscribes,

Since ‘spite of him I’ll live in this poor rhyme,

While he insults o’er dull and speechless tribes.

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent.

How very confident de Vere is that these “verse letters” are going to comprise a “monument” for Southampton that will outlive the crests of tyrants and the brass tombs of kings! As Oxford promised him in Sonnet 81:

Your monument shall be my gentle verse,

Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read…

And now, proceeding from the climax of number 107, the story’s resolution unfolds in nineteen days covered by exactly nineteen sonnets, advancing with increasing power and grandeur to the funeral procession bearing the coffin and effigy of Elizabeth under a canopy, on April 28, 1603, marked by Sonnet 125, the official end of the Tudor dynasty, followed immediately by the author’s envoy of farewell to “Oh thou my lovely Boy.”

The result is a self-contained series of the 80 prison sonnets plus the 20 sonnets of resolution, exactly 100 sonnets or a “century” of them – mirroring Hekatompathia, or the Passionate Century of Love (1582), the 100 consecutively numbered sonnets attributed to Thomas Watson and dedicated to Oxford. The “century” within SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS is the central sequence of his monument for Southampton.

The younger earl will live on, but the author will disappear. Oxford consistently expresses this sacrifice of one life for the other — the exchange of his life or identity as “Shakespeare” for Southampton’s life as a free man:

When I, perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse. (Sonnet 71)

(When I am dead, you will continue without acknowledging me.)

My name be buried where my body is

And live no more to shame nor me nor you. (Sonnet 72)

(My identity will disappear, leaving you to flourish)

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die. (Sonnet 81)

(You are forever tied to “Shakespeare,” while I must disappear.)

In effect, these lines of the Sonnets comprise Edward de Vere’s own version of Hamlet’s cry for his wounded name. It’s a tragic story, but also the basic answer to the Shakespeare Authorship Question, delivered to posterity by the author himself — as he talks about his “poor name” or “name” to be “buried” and stating that he himself must die – not just in the physical sense, of course, but to “all the world.” He disconnects himself from “Shakespeare” and, therefore, from Southampton, ensuring that his own identity will disappear … but not forever!

In fact, Oxford is counting on these very sonnets to “tell my story,” as Hamlet begs his friend Horatio. Back in Sonnet 55, when Southampton’s fate was by no means certain, Oxford vowed to create “the living record of your memory,” adding:

’Gainst death and all-oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth! Your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

In this way he will triumph over Time and defeat the false “registers” or “records” upon which the future writers of history will rely. He himself will prevail in these sonnets, which will be printed in 1609 only to be quickly suppressed and driven underground, until the quarto’s reappearance more than a full century later. And so he defeats Time and Cecil and even Death, as expressed in Sonnet 107: “I’ll live in this poor rhyme.”

He draws his breath in pain, to tell his story. The “monument” of the Sonnets is his ultimate triumph, as expressed in Sonnet 123:

No! Time, thou shalt not boast that I do change!

Thy pyramids built up with newer might

To me are nothing novel, nothing strange:

They are but dressings of a former sight.

Our dates are brief, and therefore we admire

What thou dost foist upon us that is old,

And rather make them borne to our desire

Than think that we before have heard them told.

Thy registers and thee I both defy –

Not wond’ring at the present, nor the past,

For thy records and what we see doth lie,

Made more or less by thy continual haste.

This I do vow, and this shall ever be:

I will be true, despite thy scythe and thee.

/////

Published in:

on December 5, 2019 at 11:21 am

Comments (7)

Tags: 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford, authorship, dover Wilson, Duncan-jones, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, Lara Crowley, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth 1, richard II, Richard III, robert cecil, shakespeare authorship, shakespeare's globe, shakespearean authorship trust, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare, William Cecil

Tags: 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford, authorship, dover Wilson, Duncan-jones, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, Lara Crowley, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth 1, richard II, Richard III, robert cecil, shakespeare authorship, shakespeare's globe, shakespearean authorship trust, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare, William Cecil

Second Edition (Revised Text) of “Hidden in Plain Sight” by Peter Rush

“Hidden in Plain Sight” is available here at Amazon.com…

“The Monument” is available here at Amazon.com…

Published in:

on May 19, 2016 at 10:02 am

Comments (3)

Tags: authorship, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, sonnet 107, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore

Tags: authorship, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, sonnet 107, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore

“The Two Most Noble Henries” – Henry de Vere & Henry Wriothesley – No. 89 of 100 Reasons why the 17th Earl of Oxford was “Shakespeare”

“The Portraicture of the right honorable Lords, the two most noble HENRIES revived the Earles of Oxford and Southampton” –

circa 1624

“There were some gallant spirits that aimed at the Public Liberty more than their own interest … among which the principal were Henry, Earl of Oxford, Henry, Earl of Southampton … and divers others, that supported the old English honor and would not let it fall to the ground.” – Arthur Wilson, History of Great Britain (1653), p. 161, referring to the earls’ opposition to the policies of King James in 1621

Venus and Adonis was recorded in the Stationer’s Register on April 18, 1593 and published soon after. No author’s name appeared on the title-page, but the dedication was signed “William Shakespeare” – the first appearance of that name in print.

The epistle was addressed to nineteen-year-old Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, to whom the poet bequeathed Lucrece the following year. Never again would this author dedicate anything to anyone else, thereby uniquely linking Southampton to “Shakespeare” for all time. In fact the poet was so confident of his ability to grant the young earl enduring fame (while paradoxically being certain his own identity would never be known) that he would tell him in Sonnet 81:

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I (once gone) to all the world must die.

On February 24, 1593, less than two months before the registry of Venus and Adonis, a son was born to Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford, forty-three, and his second wife Elizabeth Trentham, about thirty, a former Maid of Honor to Queen Elizabeth. The two had married in 1591 and had moved to the village of Stoke-Newington, just north of Shoreditch and the Curtain and Theater playhouses.

The boy, destined to become the eighteenth Earl of Oxford, was brought to the Parish Church on March 31, 1593 and christened Henry de Vere – not Edward, after his father, nor any of the great first names in the Vere lineage (such as John or Robert) all the way back to 1141, when Aubrey de Vere was created the first Earl of Oxford.

“It is curious that the name ‘Henry’ is unique in the de Vere, Cecil and Trentham families,” B.M. Ward commented in 1928. “There must have been some reason for his being given this name, but if so I have been unable to discover it.”

During this time Henry Wriothesley was being sought by William Cecil Lord Burghley for the hand of Oxford’s eldest daughter, Lady Elizabeth Vere. Oxford had become a royal ward in Burgley’s household in 1562; Southampton had followed in 1581; and now on April 18, 1593, little more than two weeks after the christening of Oxford’s male heir as Henry de Vere, the yet-unknown “Shakespeare” was dedicating “the first heir of my invention” to Henry Wriothesley.

“The metaphor of ‘the first heir’ would seem to echo the recent birth of Oxford’s only son and heir to his earldom,” J. Thomas Looney noted in 1920, “and as ‘Shakespeare’ speaks of Southampton as the ‘godfather’ of ‘the first heir of my invention,’ it would certainly be interesting to know whether Henry Wriothesley was godfather to Oxford’s heir, Henry de Vere.”

In the dedication of Lucrece in 1594, the author made a unique public promise to Southampton, indicating a close and caring relationship with its own past, coupled with an extraordinary vision of future commitment:

“The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end … What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours.”

Given that Henry Wriothesley is the only individual to whom “Shakespeare” is known to have written any letters of any kind, he must be the central contemporary individual within the biography of Shakespeare the poet and dramatist. (This is especially so if Southampton is the younger man or “fair youth” of the Sonnets.) The problem, however, is that scholars have never discovered any trace of a relationship between Southampton and William Shaksper of Stratford-upon-Avon, not even any evidence that they knew each other.

But if the poet was Edward de Vere, dedicating his first published work under the newly invented pen name “Shakespeare” to Henry Wriothesley, then his promise that “what I have to do is yours” demands a look into the future for evidence of continuing linkage.

Among the possible evidence is the performance of Richard II as by “Shakespeare” on the eve of the Essex Rebellion on February 8, 1601 led by Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex along with Southampton. If Oxford was the dramatist, had he given permission to use his play for such a dangerous and possibly treasonous motive? Had he given his approval personally to Southampton, to help him? These are among the many questions for which history has no answers.

Looney pointed to a “spontaneous affinity of Oxford with the younger Earls of Essex and Southampton, all three of whom, having been royal wards under the guardianship of Burghley, were most hostile to the Cecil influence at Court.” By the same token, many scholars have noted evidence in the “Shakespeare” plays that the author was sympathetic to the Essex faction – which makes sense if Oxford and “Shakespeare” were one and the same.

Notice of the trial of Essex and Southampton

1600 old style 1601 new

Oxford as highest ranking peer on tribunal

[Oxford was summoned from retirement to act as the senior of twenty-five noblemen on the tribunal at the joint treason trial of Essex and Southampton on February 19, 1601. The peers had no choice but to render a unanimous guilty verdict and to sentence both earls to death. It was “the veriest travesty of a trial,” Ward comments. Essex was beheaded six days later, but Southampton was spared; and after more than two years in prison, he was quickly released by the newly proclaimed King James. CLICK ON IMAGE FOR LARGER VIEW.]

Oxford is recorded as having died at fifty-four on June 24, 1604. That night agents of the Crown arrived at Southampton’s house in London, confiscating his papers and bringing him (and others who had supported Essex) back to the Tower, where he was interrogated before being released the next day. Whether the two events (Oxford’s death and Southampton’s arrest) were related remains a matter of conjecture.

In January 1605, Southampton hosted a performance of Love’s Labours Lost for Queen Anne. The earl apparently had not forgotten how, in the early 1590s, he and his university friends had enjoyed private performances of the play.

In the latter years of James both Henry Wriothesley and Henry de Vere became increasingly opposed to the King’s favorite George Villiers, first Duke of Buckingham, and the projected Spanish match between the King’s son Prince Charles and Maria Ana of Spain – fearing that Spain would grow even stronger to the point of conquering England and turning it back into a repressive Catholic country.

On March 14, 1621, Henry Wriothesley, forty-eight, got into a sharp altercation with Buckingham in the House of Peers; that June he was confined (in the Dean of Westminster’s house and later in his own seat of Tichfield) on charges of “mischievous intrigues” with members of the Commons; and in July of the same year, Henry de Vere, twenty-eight, spent a few weeks in the Tower for expressing his anger toward the prospective Spanish match. Henry Wriothesley was set free on the first of September.

Then on April 20, 1622, after railing against Buckingham again, Henry de Vere was arrested for the second time and confined in the Tower for twenty months until December 1623 – just when the First Folio of Shakespeare plays became available for purchase.

[Whatever might have been the relationship between the imprisonment of Oxford and the publishing of the Folio is unclear; my own feeling is that the printing may well have been spurred by the prospect of Spanish control and the destruction of the Shakespeare plays, especially the eighteen yet to be printed. The Spanish marriage had collapsed in October 1623; but any opinions about whether the Folio printing was triggered by the prospect of the match, and/or the imprisonment of the eighteenth Earl of Oxford are welcome.]

When Henry de Vere volunteered for military service to the Protestant cause in the Low Countries in June 1624, as the colonel of a regiment of foot soldiers, he put forward a “claim of precedency” over his fellow colonel of another regiment, Henry Wriothesley. Eventually the Council of War struck a bargain between the two, with Oxford entitled to precedency in civil capacities and Southampton, “in respect of his former commands in the wars,” retaining precedence over military matters.

[The colonels of the other two regiments were Robert Devereux, third Earl of Essex, the son of Southampton’s great friend Essex, who was executed for the 1601 rebellion; and Robert Bertie, Lord Willoughby, son of Edward de Vere’s sister Mary Vere and his brother-in-law Peregrine Bertie, Lord Willoughby.]

“There seems to have been no ill will between Southampton and Oxford,” writes A.L. Rowse in his biography Shakespeare’s Southampton. “They were both imbued with conviction and fighting for a cause for which they had long fought politically. It was now a question of carrying their convictions into action, sacrificing their lives.”

Southampton and his elder son James (born in 1605) sailed for Holland in August 1624; in November, the earl’s regiment in its winter quarters at Roosendaal was afflicted by fever. Father and son both caught the contagion; the son died on November 5, 1624; and Southampton, having recovered, began the long sad journey with his son’s body back to England. Five days later, however, Southampton himself died at Bergen-op-Zoom at fifty-one. [A contemporary report was that agents of Buckingham had poisoned him to death.]

King James died on March 25, 1625 and Henry de Vere, eighteenth Earl of Oxford died at The Hague on July 25 that year, after receiving a shot wound on his left arm.

But why, after all, might the “Two Henries” be another reason to conclude that Edward de Vere was the real author of the Shakespeare works? Well, to begin with, in this story there is not a trace of the grain dealer and moneylender from Stratford; he is nowhere to be found. More important, however, is the obviously central role in the authorship story played by Henry Wriothesley, who went on to embody the spirit of the “Shakespeare” and the Elizabethan age – the great spirit of creative energy, of literature and drama, of romance and adventure, of invention and exploration, of curiosity and experimentation, of the Renaissance itself.

And, too, Southampton had become a kind of father figure to the sons of Oxford and Essex and Willoughby – the new generation of those “gallant spirits that aimed at the Public Liberty more than their own interest” and who “supported the old English honor and would not let it fall to the ground.”

How these men must have shared a love for “Shakespeare” and his stirring words! How they must have loved speeches such as the one spoken by the Bastard at the close of King John:

This England never did, nor never shall,

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror

But when it first did help to wound itself.

Now these her princes are come home again,

Come the three corners of the world in arms,

And we shall shock them. Nought shall make us rue

If England to itself do rest but true!

POSTSCRIPT

Oxfordian researcher and author Robert Brazil wrote the following on this topic in his book The True Story of the Shake-speare Publications: Edward de Vere and the Shakespeare Printers:

“In the 1600s Oxford’s son Henry became a very close friend to Henry Wriothesley. They shared a passion for politics, theater, and military adventure. The image of the Two Henries, which dates from 1624 or later, shows the earls of Oxford and Southampton riding horseback together in their co-command of the 6000 English troops in Holland that had joined with the Dutch forces in countering the continued attacks by Spain. The picture serves as a reminder that a close relationship between the Vere family and Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, lasted for decades, and that Southampton CAN be linked historically to the author Shake-speare, provided that said author was really Edward de Vere.”

Published in:

on March 1, 2014 at 11:00 pm

Comments (5)

Tags: Anonymous, authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, Henry de Vere, henry wriothesley, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: Anonymous, authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, Henry de Vere, henry wriothesley, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“And Your True Rights Be Termed a Poet’s Rage…”

Here’s the Front Cover, Back Cover and Table of Contents for an important new book just published (For a larger view, click on each image):

Published in:

on August 17, 2013 at 8:07 am

Leave a Comment

Tags: alex mcneil, authorship, charles beauclerk, charles boyle, daniel wright, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth 1, roland emmerich, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare, William Boyle, William Plumer Fowler

Tags: alex mcneil, authorship, charles beauclerk, charles boyle, daniel wright, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth 1, roland emmerich, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare, William Boyle, William Plumer Fowler

“To Play the Watchman Ever for Thy Sake” – Sonnet 61 of the Living Record of Southampton

THE PRISON YEARS

DAY THIRTY-FIVE IN THE TOWER

SOUTHAMPTON EXECUTION APPEARS IMMINENT

Sonnet 61

“To Play the Watchman Ever for Thy Sake”

14 March 1601

Oxford records his attempt to keep Southampton in his mind’s eye at all times, as events lead either to his son’s execution or to a reprieve. His royal son must wake each new day “elsewhere” — in the Tower — and yet Oxford continues to “play the watchman” and stand guard to protect Henry Wriothesley’s life.

1 – Is it thy will thy Image should keep open

2 – My heavy eyelids to the weary night?

3 – Dost thou desire my slumbers should be broken,

4 – While shadows like to thee do mock my sight?

5 – Is it thy spirit that thou send’s from thee

6 – So far from home into my deeds to pry.

7 – To find out shames and idle hours in me,

8 – The scope and tenure of thy jealousy?

9 – O no, thy love, though much, is not so great.

10 – It is my love that keeps mine eye awake,

11 – Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat,

12 – To play the watchman ever for thy sake.

13 – For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere,

14 – From me far off, with others all too near.

1 IS IT THY WILL THY IMAGE SHOULD KEEP OPEN

THY WILL = your royal will; is it your royal will that the image of you should keep open; IMAGE = your royal image; “if in the child the father’s image lies” – Lucrece, 1753; “our last king, whose image appeared to us” – Hamlet, 1.1.81

2 MY HEAVY EYELIDS TO THE WEARY NIGHT?

MY HEAVY EYELIDS = my weary, painful eyelids in the dark; “How heavy do I journey on the way” – Sonnet 50, line 1, Oxford recalling his sorrowful ride away from Southampton in the Tower, where he told his son of the bargain to save his life by giving up all claim to the throne; “And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,/ Looking on darkness which the blind do see” – Sonnet 27, lines 7-8; “And heavily from woe to woe” – Sonnet 30, line 10; “When in dead night thy fair imperfect shade/ Through heavy sleep on sightless eyes doth stay!” – Sonnet 43, lines 11-12; “But heavy tears, badges of either’s woe” – Sonnet 44, line 14

“And find our griefs heavier than our offences” – 2 Henry IV, 4.1.69

“A heavy reckoning for you, sir” – The Gaoler in Cymbeline, 5.4.157

WEARY = “Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed” – Sonnet 27, line 1, Oxford’s first response to the Rebellion, on the night of February 8, 1601, when Southampton was imprisoned with Essex in the Tower; “for to tell truth I am weary of an unsettled life, which is the very pestilence that happens unto courtiers that propound to themselves no end of their time therein bestowed” – Oxford to Burghley, May 18, 1591; NIGHT = opposite of the “day” of golden opportunity prior to the Rebellion

I still do toil and never am at rest,

Enjoying least when I do covet most;

With weary thoughts are my green years oppres’d

– Signed “Lo. Ox” in Harleian MS

3 DOST THOU DESIRE MY SLUMBERS SHOULD BE BROKEN,

DESIRE = royal command; “From fairest creatures we desire increase” – Sonnet 1, line 1, emphasizing the royal “we” of the monarch

4 WHILE SHADOWS LIKE TO THEE DO MOCK MY SIGHT?

SHADOWS LIKE TO THEE = the shadows that cover you, showing your likeness; “Save that my soul’s imaginary sight/ Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,/ Which like a jewel hung in ghastly night,/ Makes black night beauteous and her old face new” – Sonnet 27, lines 9-12; “What is your substance, whereof are you made,/ That millions of strange shadows on you tend?/ Since every one hath, every one, one shade,/ And you, but one, can every shadow lend” – Sonnet 53, lines 1-4; MOCK MY SIGHT = mock my eyesight, taunting me with this inner vision of you

5 IS IT THY SPIRIT THAT THOU SEND’ST FROM THEE

THY SPIRIT = your soul; your royal blood, which is spiritual; like a mystical vision; “and do not kill/ The spirit of love” – Sonnet 56, lines 7-8, i.e., the unseen essence of royal blood; “My spirit is thine, the better part of me” – Sonnet 74, line 8; SPIRIT = also Sonnets 80, 85, 86, 108, 129, 144; Essex wrote to Elizabeth in 1597 calling her “the Spirit of spirits” (Weir, 427); THAT THOU SEND’ST FROM THEE = Southampton sends his spirit and illuminates Oxford’s inner vision: “Save that my soul’s imaginary sight/ Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,/ Which like a jewel (hung in ghastly night)/ Makes black night beauteous, and her old face new” – Sonnet 27, lines 9-11

6 SO FAR FROM HOME INTO MY DEEDS TO PRY,

SO FAR FROM HOME = Southampton, in the Tower; INTO MY DEEDS TO PRY = to spy on my activities, carried out behind the scenes, on your behalf; “Or on my frailties why are frailer spies” – Sonnet 121, line 7; “Watch thou, and wake when others be asleep, to pry into the secrets of the state” – 2 Henry VI, 1.1.250-251

7 TO FIND OUT SHAMES AND IDLE HOURS IN ME,

TO FIND OUT SHAMES = to learn the disgraces that I suffer, by taking responsibility for your disgrace; “If thy offences were upon record, would it not shame thee, in so fair a troop, to read a lecture of them? If thou wouldst, there shouldst thou find one heinous article, containing the deposing of a king” – Richard II, 4.1.230-234); IDLE HOURS = time spent pleading for you in vain; “I … vow to take advantage of all idle hours, till I have honoured you with some graver labour” – dedication of Venus and Adonis in 1593 to the Earl of Southampton; “That never am less idle lo, than when I am alone” – Oxford poem, signed E.O., in The Paradise of Dainty Devices, 1576

Had he done so, himself had borne the crown,

Which waste of idle hours hath quite thrown down – Richard II, 3.4.65-66

8 THE SCOPE AND TENURE OF THY JEALOUSY?

SCOPE = “Three themes in one, which wondrous scope affords” – Sonnet 105, line 12; that to which the mind is directed; “shooting wide, do miss the marked scope” – Spenser, The Shepherd’s Calendar, November, 155; SCOPE AND TENURE = the purpose and “tenor” or meaning; Q has tenure, a common spelling of “tenor” at the time, but tenure is probably the intended word, as it relates to the “lease” of Southampton’s royal blood, i.e., tenure refers to the manner of holding lands and tenements, a subject with which Oxford was extremely familiar, having inherited no less than eighty-six estates; THY JEALOUSY = your curiosity; your apprehension; your state of being suspected as a traitor or being a “suspect traitor” in the eyes of the law; “Rumor is a pipe blown by surmises, jealousies, conjectures” – 2 Henry IV, Induction 16; concerned about; “So loving-jealous of his liberty” – Romeo and Juliet, 2.2.182

9 O NO! THY LOVE, THOUGH MUCH, IS NOT SO GREAT:

THY LOVE, THOUGH MUCH = your royal blood, though abundant; IS NOT SO GREAT = is not as great as it is within Oxford’s vision of him, as father

10 IT IS MY LOVE THAT KEEPS MINE EYE AWAKE,

MY LOVE = my royal son; i.e., it is the fact that you are my royal son that keeps me from taking my own life, keeps me awake; AWAKE = in a state of vigilance; alert, alive, attentive, watchful; “It is not Agamemnon’s sleeping hour: that thou shalt know, Trojan, he is awake, he tells thee so himself” – Agamemnon in Troilus and Cressida, 1.3.252-254; “I offered to awaken his regard for his private friends” – Coriolanus, 5.1.23; “The law hath not been dead, though it hath slept … Now ‘tis awake” – Measure for Measure, 2.2.91-94; “Watch thou, and wake when others be asleep, to pry into the secrets of the state” – 2 Henry VI, 1.1.250-251

11 MINE OWN TRUE LOVE THAT DOTH MY REST DEFEAT,

MINE OWN TRUE LOVE = my own true royal son; (“a son of mine own” – Oxford to Burghley, March 17, 1575; “Not mine own fears nor the prophetic soul/ Of the wide world dreaming on things to come/ Can yet the lease of my true love control” – Sonnet 107, lines 1-3); TRUE = Oxford, Nothing Truer than Truth; “you true rights” – Sonnet 17, line 11, to Southampton; MINE OWN: Sonnets 23, 39, 49, 61, 62, 72, 88, 107, 110; (“Rise, thou art my child … Mine own…” – Pericles, 5.1.213-214, the prince, realizing that Marina is his daughter); MY REST DEFEAT = destroy my inner peace; “His unkindness may defeat my life” – Othello, 4.2.150; “The dear repose for limbs with travail tired” – Sonnet 27, line 1; “That am debarred the benefit of rest” – Sonnet 28, line 2; “Now this ill-wresting world is grown so bad” – Sonnet 140, line 11, to Elizabeth in the Dark Lady series, with ill-wresting echoing ill-resting. s

12 TO PLAY THE WATCHMAN EVER FOR THY SAKE.

TO PLAY THE WATCHMAN EVER = to constantly keep guard and protect; EVER = E. Ver, Edward de Vere; Oxford used “ever” in the same glancing way in his plays, such as these instances in Hamlet, Prince of Denmark:

Horatio: The same, my lord, and your poor servant ever.

Hamlet: Sir, my good friend, I’ll change that name with you. (1.2.162-163)

FOR THY SAKE = for your royal life here and now; for your eternal life, recorded in these sonnets filled with your royal blood

13 FOR THEE WATCH I, WHILST THOU DOST WAKE ELSEWHERE,

FOR THEE WATCH I = for you I keep watch; “Whilst I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you” – Sonnet 57, line 6; “Therefore I have entreated him along with us to watch the minutes of the night, that if again this apparition come, he may approve our eyes and speak to it” – Hamlet, 1.1.29-32; WHILST THOU DOST WAKE ELSEWHERE = while you – Southampton – exist in the Tower; WAKE = echoing the “wake” related to a funeral; “There is no doubt that the poor, especially in the more remote counties of England, continued the old custom of the wake, or nightly feasting before and after a funeral. Shakespeare uses the word in connection with a night revel in Sonnet 61: ‘For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere.’” – Percy Macquoid in Shakespeare’s England, Vol. 2, 196, p. 151; Oxford knows Southampton is in the Tower, of course, but he cannot know exactly where or if, for example, Southampton has been taken to the Privy Council room in the Tower for questioning, to one of the torture rooms, or even to the place of execution; the situation is still volatile, with Cecil having the power of life or death and holding the threat of legal execution over him; so the echo of a “wake” preceding a funeral is quite apt.

14 FROM ME FAR OFF, WITH OTHERS ALL TOO NEAR.

FROM ME FAR OFF = Southampton, far from him, behind the high fortress walls; WITH OTHERS ALL TOO NEAR = with guards and other prisoners alike; with some of the latter, arrested for the Rebellion, who may urge you to escape or to attempt another revolt; those so physically near you that, despite their wakefulness, they are blind and cannot protect you (or save your life); but Oxford as his father is “nearer” to him than they are, and he is helping him more than they can help; “You twain, of all the rest, are nearest to Warwick by blood and by alliance” – 3 Henry VI, 4.1.133-134; “as we be knit near in alliance” – Oxford to Robert Cecil, his brother-in-law, February 2, 1601; “Whereby none is nearer allied than myself” – Oxford to Robert Cecil in May 1601; ALL = Southampton

Published in: Uncategorized

on June 6, 2013 at 11:15 pm

Comments (21)

Tags: authorship, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Sonnet 61, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Sonnet 61, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Execution of Southampton Draws Nearer — “The Living Record” of Southampton, Continued — Sonnet 60

(Note: This is a continuation of postings from “The Monument,” with excerpts of The Sonnets in numerical [and chronological] order with the first long series [1 to 126] focusing on the Earl of Southampton. In due time the previous postings will be shifted into the new separate category [at right] entitled “The Living Record of Southampton.”)

THE PRISON YEARS

EXECUTIONS OF MERRICK & CUFFE

Southampton Execution Draws Nearer

Day Thirty-four in the Tower

Sonnet 60

“Our Minutes Hasten to their End”

“Crooked Eclipses ‘Gainst His Glory Fight”

13 March 1601

Essex-Southampton supporters Gelly Merrick and Henry Cuffe were taken today to Tyburn, where they were put through the horrible ordeal of being hanged, drawn and quartered. Oxford uses the royal imagery of the Ocean or Sea to envision the “changing place” or alteration of monarchs upon the royal succession. He refers to the crooked figure of hunchbacked Secretary Robert Cecil in citing the “crooked eclipses” fighting to deprive Southampton of being “crowned” with “glory” as a king. Oxford braces himself for the moment Southampton will come under the “scythe” or blade of the executioner as well as the “cruel hand” of Elizabeth — reminiscent of when their newly born royal son had been “by a Virgin hand disarmed” as put in Sonnet 154 of the Bath prologue.

1 – Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

2 – So do our minutes hasten to their end,

3 – Each changing place with that which goes before,

4 – In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

5 – Nativity, once in the main of light,

6 – Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned,

7 – Crooked eclipses ‘gainst his glory fight,

8 – And time that gave doth now his gift confound.

9 – Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth,

10 – And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow,

11 – Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth,

12 – And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow.

13 – And yet to time in hope my verse shall stand,

14 – Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

“At the gallows Cuffe declared that he hoped for salvation in the atonement of his Savior’s blood … and asking pardon of God and the Queen, he was despatched by the executioner. After him Sir Gelly Merrick suffered in the same way … and intreated those noblemen who stood by to intercede with the Queen that there might not be any further proceedings against such as had unwarily espoused this unhappy cause.”- An Elizabethan Chronicle

“As every wave drives others forth, and that comes behind/ Both thrusteth and is thrust himself; even so the time by kind/ Do fly and follow both at once and evermore renew” – Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” as translated by Oxford’s uncle Arthur Golding

1 LIKE AS THE WAVES MAKE TOWARDS THE PEBBLED SHORE,

WAVES = related to the “ocean” of royal blood; (“’Thou art,’ quoth she, ‘a sea, a sovereign king, and lo there falls into thy boundless flood black lust, dishonor, shame, misgoverning, who seek to stain the ocean of thy blood.’ – Lucrece, 652-654); image of King James succeeding Elizabeth

2 SO DO OUR MINUTES HASTEN TO THEIR END,

OUR MINUTES = the time we have left, the actual minutes racing onward; HASTEN = “How like a Winter hath my absence been/ From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year” – Sonnet 97, lines 1-2; “And all in war with Time for love of you” – Sonnet 15, line 13; THEIR END = the end of these minutes, ending your life or ending Elizabeth’s reign; the end of this diary, which is leading to the time of royal succession, when the fate of the Tudor dynasty will be determined; “Thy end is Truth’s and Beauty’s doom and date” – Sonnet 14, line 14

3 EACH CHANGING PLACE WITH THAT WHICH GOES BEFORE,

CHANGING PLACE = succeeding to the throne, replacing one monarch with another; the succession that will inevitably come, just as the tide inevitably rolls in; “And says that once more I shall interchange my waned state for Henry’s regal crown” – 3 Henry VI, 4.7.3-4; “Arise, and take place by us” – the King in Henry VIII, 1.2.13; “I fear there will a worse come in his place” – of Caesar in Julius Caesar, 3.2.112; “That then I scorn to change my state with Kings” – Sonnet 29, line 14; also echoing his royal son as a “changeling” who had been “placed” in the Southampton household, changing places with another boy; “placed it safely, the changeling never known” – Hamlet, 5.2.53; “Even so have places oftentimes exchanged their estate” – Ovid’s Metamorphoses of 1567, Book XV, 287, the translation attributed to Oxford’s uncle Arthur Golding

CHANGING = the change from one royal decree to another; “shifting change” – Sonnet 20, line 4, referring to Elizabeth’s change of attitude, the breaking of her vows; “Where wasteful time debateth with decay, /To change your day of youth to sullied night” – Sonnet 15, lines 11-12; exchanging, substituting; anticipating the death of Elizabeth, the downfall of his son, Southampton, as king and the accession of James; “the state government was changed from kings to consuls” – the “Argument” of Lucrece; ““When I have seen such interchange of state” – Sonnet 64, line 9; “Creep in ‘twixt vows, and change decrees of Kings” – Sonnet 115, line 6; “And lean-looked prophets whisper fearful change … These signs foretell the death or fall of kings” – Richard II, 2.4.11-15; “Comets, importing change of time and state” – 1 Henry VI, 1.1.2; “Why is my verse so barren of new pride,/ So far from variation or quick change” – Sonnet 76, lines 1-2; “And in this change is my invention spent” – Sonnet 105, line 11; “Just to the time, not with the time exchanged” – Sonnet 109, line 7, referring to the change from the time of Elizabeth to the time of James; “No! Time, thou shalt not boast that I do change!” – Sonnet 123, line 1

PLACE = echoing the “place” where Southampton is, i.e., the Tower: “As soon as think the place where he would be” – Sonnet 44, line 8; his “place” on the throne, as he tells Elizabeth: “Thy black is fairest in my judgment’s place” – Sonnet 131, line 12; “Finding yourself desired of such a person whose credit with the judge, or own great place, could fetch your brother from the manacles of the all-binding law” – Measure for Measure, 2.4.91-94

4 IN SEQUENT TOIL ALL FORWARDS DO CONTEND.

SEQUENT = “following, successive, consequent” – Schmidt; “Not merely successive, but in close succession” – Tucker; “Of six preceding ancestors, that gem conferred by testament to th’sequent issue” – All’s Well That Ends Well, 5.3.196-197; in sequence or royal succession; (“How art thou a king but by fair sequence and succession” – Richard II, 2.1.199); these private sonnets are numbered sequentially, reflecting the days that contain the onrushing hours and minutes leading to the succession; more immediately, leading to the still possible execution of Southampton

Then, good prince,

No longer session hold upon my shame,

But let my trial be mine own confession.

Immediate sentence, then, and sequent death

Is all the grace I beg. — Measure for Measure, 5.1.367-371

TOIL = labor, struggle; ALL = Southampton; ALL FORWARDS DO CONTEND = all new princes contend for the throne; “Time’s glory is to calm contending kings” – Lucrece, 939; “let his grace go forward” – Henry VIII, 3.2.281; “Friends that have been thus forward in my right” – Titus Andronicus, 1.1.59; “The forward violet thus did I chide” – Sonnet 99, line 1, referring to his royal son as flower; “When a man’s verses cannot be understood, nor a man’s good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room” – As You Like It, 3.3.11-14; CONTEND = to strive; to quarrel, combat, fight, make war ; vie with; “For never two such kingdoms did contend without much fall of blood, whose guiltless drops are every one a woe” – Henry V, 1.2.24-26; “The red rose and the white are on his face, the fatal colours of our striving houses … If you contend, a thousand lives must wither” – 3 Henry VI, 2.5.97-102

5 NATIVITY, ONCE IN THE MAIN OF LIGHT

NATIVITY = birth; the royal birth of Southampton (“the little Love-God” of Sonnet 154), echoing the Nativity of Christ; “To whom the heavens in thy nativity adjudged an olive branch and laurel crown” – 3 Henry VI, 4.6.33-34; “a god on earth thou art” – to Bolinbroke as King in Richard II, 5.3.134; ONCE = during his golden time up through the year 1600, prior to the Rebellion; echoing “one” for Southampton, One for All, All for One; similar to “first” as in “Even as when first I hallowed thy fair name” – Sonnet 108, line 8, carrying forward the Christ theme; MAIN = full might; the principal point; the ocean itself, the great (royal) sea: “When I have seen the hungry Ocean gain/ Advantage on the kingdom of the shore,/ And the firm soil win of the watery main” – Sonnet 64, lines 5-7; “But since your worth, wide as the Ocean is/ … On your broad main doth willfully appear” – Sonnet 80, lines 5, 8; “A substitute shines brightly as a king until a king be by, and then his state empties itself, as doth an inland brook into the main of waters” – The Merchant of Venice, 5.1.94-97; “by commission and main power” – Henry VIII, 2.2.7; IN THE MAIN OF LIGHT = filled with royal blood; (“the sun, suggested by main of light, of which it is the literal inhabitant” – Booth); echoing the birth of “my Sunne” recalled in Sonnet 33: “Full many a glorious morning have I seen/ Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye,/ Kissing with golden face the meadows green,/ Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy/ … Even so my Sunne one early morn did shine” – Sonnet 33, lines 1-4, 9; also indicating (in the next lines) that such glory (on earth) is no longer his; “When thou thyself dost give invention light” – Sonnet 38, line 8; “the entrance of a child into the world at birth is an entrance into the main or ocean of light” – Dowden, offering (without intending to) more evidence of Oxford writing as father to son; LIGHT = Oxford is attempting to shine the light of his son’s royalty into the darkness of his disgrace and loss of the throne; “to lend the world his light” – Venus to Adonis in Venus and Adonis, dedicated to Southampton, 1593, line 756; Southampton, godlike, is a royal star or sun, lending light to the world; he is also a jewel, emitting light, as do his eyes; “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light” – Genesis, 1.3; “In him was life; and the life was the light of men” – Gospel of John, 1.4; “Dark’ning thy power to lend base subjects light” – Sonnet 100, line 4, Oxford speaking of the power of his Muse to restore light to his royal son branded as a “base” criminal or traitor; “Lo, in the Orient when the gracious light/ Lifts up his burning head” – Sonnet 7, lines 1-2; “thy much clearer light” – Sonnet 43, line 7; “those suns of glory, those two lights of men” – Henry VIII, 1.1.6, referring to men as “suns” of light; “Yet looks he like a king; behold, his eye, as bright as is the eagle’s, lightens forth controlling majesty” – Richard II, 3.3.68-71; “That in black ink my love may still shine bright” – Sonnet 65, line 14

“I have engaged myself so far in Her Majesty’s service to bring the truth to light” – Oxford to Burghley, June 13, 1595

6 CRAWLS TO MATURITY, WHEREWITH BEING CROWNED,

CRAWLS TO MATURITY = Southampton, gaining full maturity; WHEREWITH BEING CROWNED = Whereupon, just when he should be crowned as king; “wherein I do not doubt she is crowned with glory” – Oxford to Robert Cecil, April 25/27, 1603, speaking of the deceased Elizabeth just before her funeral; (“Add an immortal title to your crown” – Richard II, 1.1.24; “Make claim and title to the crown” – Henry V, 1.2.68); “Incertainties now crown themselves assured” – Sonnet 107, line 7, after Elizabeth’s death, when James is proclaimed King of England

7 CROOKED ECLIPSES ‘GAINST HIS GLORY FIGHT,

CROOKED ECLIPSES= Evil eclipses of the sun; the Queen’s (and Robert Cecil’s) malignant eclipse of the royal son, whose brightness can no longer be seen; CROOKED = Cecil as hunchback or “crook-back”; (“malignant, perverse, contrary, devious” – Crystal & Crystal); “By what by-paths and indirect crooked ways I met this crown” – 2 Henry IV, 4.5.184; (“If crooked fortune had not thwarted me” – Deut. 32.5); ECLIPSES = “The mortal Moone hath her eclipse endured” – Sonnet 107, referring to Elizabeth, whose royal lineage as a sun had been eclipsed by her death; “Clouds and eclipses stain both Moone and Sunne” – Sonnet 35, line 3, referring to the stain of treason that now eclipses the blood of both Elizabeth, the Moon, and her son

(“Note that ‘E C L I’ begins the word ‘ECLIPSE,’ and those four letters are in ‘CECIL.’ [And ‘CECIL’ contains only those four letters.] Also, there’s really no such thing as a ‘crooked eclipse,’ so perhaps he’s punning on ‘Crooked ECLIpses’ = CECIL” – Alex McNeil, ed.)

‘GAINST HIS GLORY = against the glory of his kingship; “The king will in his glory hide thy shame” – Edward III, 2.1.399; “and although it hath pleased God after an earthly kingdom to take her up into a more permanent and heavenly state, wherein I do not doubt she is crowned with glory” – Oxford to Robert Cecil, April 25/27, 1603, about Elizabeth on the eve of her funeral; “For princes are a model which heaven likes to itself: as jewels lose their glory if neglected, so princes their renown if not respected” – Pericles, 2.2.10-13; “Even in the height and pride of all his glory” – Pericles, 2.4.6; “See, see, King Richard doth himself appear, as doth the blushing discontented sun from out the fiery portal of the East, when he perceives the envious clouds are bent to dim his glory and to stain the track of his bright passage to the occident” – Richard II, 3.3.62-67; “And threat the glory of my precious crown” – Richard II, 3.3.90; “That plotted thus our glory’s overthrow” – 1 Henry VI, 1.1.24

8 AND TIME THAT GAVE DOTH NOW HIS GIFT CONFOUND.

TIME THAT GAVE = time related to the life of Elizabeth, who gave birth to him; HIS GIFT = his inheritance of royal blood; his gift of royal life from Elizabeth; “So thy great gift, upon misprision growing” – Sonnet 87, line 11; DOTH NOW HIS GIFT CONFOUND = now destroys his gift of royalty and his claim to the throne; CONFOUND = to mingle, perplex, confuse, amaze, destroy, ruin, make away with, waste, wear away; i.e., the waste of time and royal life being recorded in this diary as “the Chronicle of wasted time” – Sonnet 106, line 1; “Against confounding age’s cruel knife” – Sonnet 63, line 10, referring to the executioner’s axe; “For never-resting time leads Summer on/ To hideous winter and confounds him there” – Sonnet 5, lines 5-6; “Or state itself confounded to decay” – Sonnet 64, line 10; “In other accents do this praise confound” – Sonnet 69, line 7

9 TIME DOTH TRANSFIX THE FLOURISH SET ON YOUTH

TIME = repeated from the previous line; TRANSFIX = destroy; “pierce [or chip] through” – Tucker; echoing the piercing of the executioner’s axe; THE FLOURISH SET ON YOUTH = the flourishing royal blood and claim that Southampton had possessed until the day of the Rebellion; “Then music is even as the flourish when true subjects bow to a new-crowned monarch” – The Merchant of Venice, 3.2.49-50

10 AND DELVES THE PARALLELS IN BEAUTY’S BROW,

PARALLELS IN BEAUTY’S BROW = wrinkles, signs of age, in Southampton’s brow, which reflects his “beauty” or blood from Elizabeth and its advancement toward death, i.e., toward execution, lack of succession; also the brow of Beauty herself, Elizabeth; Southampton had been born “with all triumphant splendor on my brow” – Sonnet 33, line 10

11 FEEDS ON THE RARITIES OF NATURE’S TRUTH,

FEEDS ON = eats up, devours; RARITIES = royal aspects; “Beauty, Truth, and Rarity” – The Phoenix and Turtle, 1601, line 53, signifying Elizabeth, Oxford, and Southampton; “With April’s first-born flowers, and all things rare” – Sonnet 21, line 7, referring to Southampton as flower of the Tudor Rose

NATURE’S TRUTH = Elizabeth’s true son by Oxford, who is Nothing Truer than Truth; “His head by nature framed to wear a crown” – 3 Henry VI, 4.6.72

12 AND NOTHING STANDS BUT FOR HIS SCYTHE TO MOW.

NOTHING = Southampton as a nobody, the opposite of “one” of his motto One for All, All for One; NOTHING STANDS = none of Southampton’s glory can withstand the ravages of real time; “Let this pernicious hour stand aye accursed in the calendar” – Macbeth, 4.1.133-134; “When peers thus knit, a kingdom ever stands” – Pericles, 2.4.58; SCYTHE = the blade of time, also the sharp blade of the executioner’s axe (“And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defence” – Sonnet 12, line 13)

13 AND YET TO TIME IN HOPE MY VERSE SHALL STAND

Nonetheless these sonnets, written according to time, hopefully will withstand – or stand against – all this destruction of his son; HOPE = “They call him Troilus, and on him erect a second hope” – Troilus and Cressida, 108-109; STAND = in counterpoint to “stands” of line 12 above; “if ought in me/ Worthy persusal stand against thy sight” – Sonnet 38, lines 5-6; “And the blots of Nature’s hand/ Shall not in their issue stand” – A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 5.1.403-404

14 PRAISING THY WORTH, DESPITE HIS CRUEL HAND.

PRAISING THY WORTH = recording your royalty; CRUEL HAND = the cruel hand of Time is the same as Elizabeth’s cruel hand, since Time represents her life; Southampton as an infant had been “by a Virgin hand disarmed” – Sonnet 154, line 8; “And shall I pray the gods to keep the pain from her, that is so cruel still … O cruel hap and hard estate … Whom I might well condemn, to be a cruel judge” – lines from three different Oxford poems, printed in The Paradise of Dainty Devices, 1576, each signed E. O.

Published in: Uncategorized

on June 1, 2013 at 8:14 am

Comments (9)

Tags: authorship, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare