“After the Rebellion” — Hank Whittemore at the Shakespearean Authorship Trust (S.A.T.) conference at Shakespeare’s Globe – November 2019

Published in:

on March 11, 2020 at 6:57 pm

Comments (2)

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, Venus and Adonis, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, Venus and Adonis, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

The Legal Mind of “Shakespeare”: Re-posting No. 43 of 100 Reasons Why the Great Author was the Earl of Oxford

“In Shakespeare’s multiple personalities, there is none in which he appears more naturally and to better advantage than in the role of the lawyer. If true that all dramatic writing is but a form of autobiography, then the immortal Shakespeare must, at some time in his life, have studied law.” – Commentaries on the Law in Shakespeare, 1911, Edward J. White

There’s not a shred of evidence that Shakspere of Stratford ever went beyond grammar school (if he attended at all), much less to a university or law school.

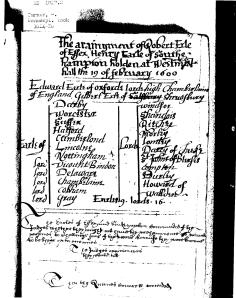

Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford served as highest-ranking nobleman on the tribunal at the February 19, 1601 treason trial of Essex and Southampton — as indicated by a contemporary notice of the event

Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford was seventeen in 1567 when he entered Gray’s Inn to study law. He was steeped in legal matters involving his earldom and the royal court; he sat on the juries at the treason trials of the duke of Norfolk (1572), Mary Queen of Scots (1586) and the earls of Essex and Southampton (1601).

A recent book, Shakespeare’s Legal Language (2000), contains a detailed discussion of Shakespeare’s legal terms and concepts. Authors B.J. Sokol and Mary Sokol point out that twenty-five of thirty-seven Shakespeare plays refer to a trial and that thirty-five contain the words “judge” and “justice.”

“Nothing adorns a king more than justice,” Oxford wrote to Robert Cecil in May 1603, referring to the newly proclaimed King James, “nor in anything doth a king more resemble God than in justice.”

Traditional scholars usually assert that Shakespeare didn’t really demonstrate an exceptional knowledge of the law, at the same time struggling to explain how he could have become so “law-obsessed,” as Sokol & Sokol put it.

Back in 1869, for example, Lord Penzance spoke of Shakespeare’s “perfect familiarity with not only the principles, axioms, and maxims, but the technicalities of English law, a knowledge so perfect and intimate that he was never incorrect and never at fault … At every turn and point at which the author required a metaphor, simile, or illustration, his mind ever turned first to the law. He seems almost to have thought in legal phrases…”

“Any intelligent writer can acquire knowledge of a subject and serve it up as required,” Charlton Ogburn Jr. writes in The Mysterious William Shakespeare, adding it is “something else to have been so immersed in a subject and to have assimilated it so thoroughly that it has become part of one’s nature, shaping one’s view of the world, coming forward spontaneously to prompt or complete a thought, supply and image or analogy.”

Oxford served on the jury at the trial of Mary Queen of Scots at Fotheringay Castle in October 1586 (drawing by Edouard Berveiller)

Mark Twain wrote in reference to Shakspere of Stratford that he “couldn’t have written Shakespeare’s works, for the reason that the man who wrote them was limitlessly familiar with the laws, and the law-courts, and law-proceedings, and lawyer-talk, and lawyer-ways—and if Shakespeare was possessed of the infinitely-divided star-dust that constituted this vast wealth, how did he get it, and where, and when? . . . A man can’t handle glibly and easily and comfortably and successfully the argot of a trade at which he has not personally served. He will make mistakes; he will not, and cannot, get the trade-phrasings precisely and exactly right; and the moment he departs, by even a shade, from a common trade-form, the reader who has served that trade will know the writer hasn’t.”

Following is a small sample of excerpts from Oxford’s letters showing his familiarity with the law and legal matters:

“But now the ground whereon I lay my suit being so just and reasonable … to conceive of the just desire I make of this suit … so by-fold that justice could not dispense any farther … The matter after it had received many crosses, many inventions of delay, yet at length hath been heard before all the Judges – judges I say both unlawful, and lawful … For counsel, I have such lawyers, and the best that I can get as are to be had in London, who have advised me for my best course … [to Queen Elizabeth]: And because your Majesty upon a bare information could not be so well satisfied of every particular as by lawful testimony & examination of credible witnesses upon oath … So that now, having lawfully proved unto your Majesty … “

Oxford attended at the House of Lords on forty-four days during the nine sessions held 1571 to 1601. In the sessions from 1585 onward he was appointed one of the “receivers and triers of petitions from Gascony and other lands beyond the seas and from the islands.” In November 1586 he was part of a committee appointed to address Elizabeth on the sentencing of Mary Queen of Scots.

In Sonnet 46, the poet describes a trial by jury:

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war

How to divide the conquest of thy sight;

Mine eye, my heart thy picture’s sight would bar

My heart, mine eye the freedom of that right;

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie

(A closet never pierced with crystal eyes),

But the defendant doth that plea deny,

And says in him thy fair appearance lies.

To ‘cide this title is impanelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart,

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eyes’ moiety, and thy dear heart’s part:

As thus, mine eyes’ due is thy outward part,

And my heart’s right, their inward love of heart.

Scholars of the Stratfordian tradition have often speculated that “Shakespeare” must have been a lawyer. The fact that Oxford himself was a lawyer does not prove that he was the great author, but it is an important piece of the accumulated evidence in his favor.

[Above is the version edited by Alex McNeil and now no. 56 of 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford.]

Published in:

on October 4, 2018 at 9:32 am

Leave a Comment

Tags: authorship, earl of oxford, edward de vere, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, earl of oxford, edward de vere, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Emmerich and “Shake-speare” and Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Earlier this month Kellvin Chavez at LATINO REVIEW asked filmmaker Roland Emmerich to discuss his movie project ANONYMOUS (formerly SOUL OF THE AGE) about Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford as “William Shakespeare” and he replied:

“Well, for me there was an incredible script that I bought eight years ago. It was called ‘Soul of the Age,’ which pretty much is the heart of the movie still. It’s three characters. It’s like Ben Jonson, who was a playwright then. William Shakespeare who was an actor. It’s like the 17th Earl of Oxford who is the true author of all these plays. We see how, through these three people, it happens that all of these plays get credited to Shakespeare. I kind of found it as too much like ‘Amadeus’ to me. It was about jealousy, about genius against end (sic?), so I proposed to make this a movie about political things, which is about succession. Succession, the monarchy, was absolute monarchy, and the most important political thing was who would be the next King. Then we incorporated that idea into that story line. It has all the elements of a Shakespeare play. It’s about Kings, Queens, and Princes. It’s about illegitimate children, it’s about incest, it’s about all of these elements which Shakespeare plays have. And it’s overall a tragedy. That was the way and I’m really excited to make this movie.”

“Well, for me there was an incredible script that I bought eight years ago. It was called ‘Soul of the Age,’ which pretty much is the heart of the movie still. It’s three characters. It’s like Ben Jonson, who was a playwright then. William Shakespeare who was an actor. It’s like the 17th Earl of Oxford who is the true author of all these plays. We see how, through these three people, it happens that all of these plays get credited to Shakespeare. I kind of found it as too much like ‘Amadeus’ to me. It was about jealousy, about genius against end (sic?), so I proposed to make this a movie about political things, which is about succession. Succession, the monarchy, was absolute monarchy, and the most important political thing was who would be the next King. Then we incorporated that idea into that story line. It has all the elements of a Shakespeare play. It’s about Kings, Queens, and Princes. It’s about illegitimate children, it’s about incest, it’s about all of these elements which Shakespeare plays have. And it’s overall a tragedy. That was the way and I’m really excited to make this movie.”

Last I heard, the cameras are expected to roll next March in Germany. Oh, Roland, you may have been controversial before, but just wait! As they say, you ain’t seen nuttin’ yet! What will the Folger do? How will the Stratford tourism industry react? The Birthplace Trust! How will teachers and professors handle the upcoming generation and its students who will be eager to investigate one of the great stories of history yet to be told?

I predict that once those floodgates open, there will be more material about this subject matter over the coming years, in print and on video or film, than on virtually any other topic. Why? Because much of the history of the modern world over the past four centuries will have to be re-written! Just think, for example, of all the biographies of other figures — such as Ben Jonson or Philip Sidney — that will have to be drastically revised to make room for the Earl of Oxford as the single greatest force behind the evolution of English literature and drama, not to mention the English language itself.

In the end, it’s not just the Literature and Drama departments that will need to change; even moreso, the History Department will be where the action is.

Onward with those floodgates!

Published in:

on November 20, 2009 at 6:29 pm

Comments (3)

Tags: Anonymous, authorship, Ben Jonson, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, mark anderson, monument, monument sonnets, Philip Sidney, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, roland emmerich, shake-speare's treason, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, Soul of the Age, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: Anonymous, authorship, Ben Jonson, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, mark anderson, monument, monument sonnets, Philip Sidney, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, roland emmerich, shake-speare's treason, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, Soul of the Age, who wrote shakespeare

“My Grief Lies Onward … From Where Thou Art … Up-Locked … Imprisoned” – Sonnets 51, 52, 53 – The Living Record, Chapter 47

I include Shakespeare’s Sonnets 50-51-52 all at once because of their obvious relationship to each other, like successive chapters of a novel — as set forth in my edition of the sonnets THE MONUMENT and dramatized in the 90-minute solo show SHAKE-SPEARE’S TREASON.

THE PRISON YEARS

OXFORD VISITS SOUTHAMPTON IN PRISON

DAY TWENTY-FOUR IN THE TOWER

Southampton was lodged in the White Tower (1601-1603)

Sonnet 50

My Grief Lies Onward

3 March 1601

Oxford rides away from the Tower of London and back to his home in Hackney, knowing he will grieve over Southampton’s execution or, even if he lives, over his loss of the throne. His joy lies behind him, in past times, and literally in the prison. In this sonnet Oxford describes his five-mile journey on horseback from the Tower and from a crucial visit with Southampton, to whom he would have explained the “league” or agreement to spare him from execution, requiring a forfeiture of any claim as King Henry IX.

How heavy do I journey on the way

When what I seek (my weary travel’s end)

Doth teach that ease and that repose to say,

“Thus far the miles are measured from thy friend.”

The beast that bears me, tired with my woe,

Plods duly on to bear that weight in me,

As if by some instinct the wretch did know

His rider loved not speed being made from thee:

The bloody spur cannot provoke him on

That sometimes anger thrusts into his hide,

Which heavily he answers with a groan,

More sharp to me than spurring to his side;

For that same groan doth put this in my mind:

My grief lies onward and my joy behind.

Heavy … Woe … Bloody … Groan … Groan … Grief – Anticipating the death of Southampton, his royal son, by bloody execution. (Meanwhile the young earl is “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom” – Sonnet 107)

OXFORD RETURNS FROM THE PRISON

DAY TWENTY-FIVE IN THE TOWER

Oxford, as Lord Great Chamberlain, would have had access to Southampton in the Tower

Sonnet 51

From Where Thou Art

4 March 1601

Oxford again describes his return home, to King’s Place in Hackney, after visiting with Southampton in the Tower – undoubtedly to discuss details of the bargain he has been making for him, involving the “excuse” for his “offence” being argued on his behalf.

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer, when from thee I speed:

From where thou art, why should I haste me thence?

Till I return, of posting is no need.

O what excuse will my poor beast then find,

When swift extremity can seem but slow?

Then should I spur, though mounted on the wind;

In winged speed no motion shall I know;

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace;

Therefore desire (of perfect’st love being made)

Shall neigh no dull flesh in his fiery race,

But love, for love, thus shall excuse my jade:

Since from thee going he went willful slow,

Towards thee I’ll run, and give him leave to go.

Offence … Excuse … Excuse – legal terms echoing Oxford’s attempts behind the scenes to act as Southampton’s legal counsel

TRIAL OF OTHER CONSPIRATORS

DAY TWENTY-SIX IN THE TOWER

Robert Cecil would have wanted Oxford to visit Southampton, to persuade him to give up any royal claim in return for the promise of freedom once James of Scotland became King of England

Sonnet 52

“Up-Locked … Imprisoned”

5 March 1601

Oxford recalls his visit to Southampton in the Tower.

An Elizabethan Chronicle, March 5, 1601 – “Today Sir Christopher Blount, Sir Charles Danvers, Sir John Davis, Sir Gelly Merrick and Henry Cuffe were arraigned at Westminster for high treason before the commissioners … They pleaded not guilty to the indictment as a whole, and a substantial jury was impanelled which consisted of aldermen of London and other gentlemen of good credit. They confessed indeed that it was their design to come to the Queen with so strong a force that they might not be resisted, and to require of her divers conditions and alterations of government; nevertheless they intended no personal harm to the Queen herself … When all the evidence was done, the jury went out to agree upon their verdict, which after half an hour’s time and more they brought in and found every man of the five prisoners severally guilty of high treason.”

The “up-locked” treasure is his son’s royal blood, imprisoned.

So am I as the rich, whose blessed key

Can bring him to his sweet up-locked treasure,

The which he will not every hour survey,

For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure;

Therefore are feasts so solemn and so rare,

Since seldom coming in the long year set,

Like stones of worth they thinly placed are,

Or captain Jewels in the carcanet.

So is the time that keeps you as my chest,

Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide,

To make some special instant special blest

By new unfolding his imprisoned pride.

Blessed are you, whose worthiness gives scope,

Being had, to triumph; being lacked, to hope.

“Thus did I keep my person fresh and new,

My presence, like a robe pontifical,

Ne’er seen but wondered at, and so my state,

Seldom, but sumptuous, show’d like a feast,

And wan by rareness such solemnity“

– The King in 1 Henry IV, 3.2.53-59

Published in: Uncategorized

on November 10, 2009 at 10:00 pm

Comments (1)

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shake-speare's treason, shakesepeare's sonnets, Shakespeare, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 107, sonnet 50, sonnet 51, sonnet 52, sonnets, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shake-speare's treason, shakesepeare's sonnets, Shakespeare, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 107, sonnet 50, sonnet 51, sonnet 52, sonnets, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“To Guard the Lawful Reasons” – The Living Record – Chapter 46

Here’s my treatment of Sonnet 49 in The Monument:

SOUTHAMPTON IN THE TOWER

DAY TWENTY-THREE

Sonnet 49

To Guard the Lawful Reasons on Thy Part

2 March 1601

- Having made a bargain with [Robert] Cecil for the life of Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, Oxford knows his royal son will “frown on my defects” for also being forced to forfeit any claim to the throne. Their public separation as father and son now has “the strength of laws” – at least, it will have such strength if and when Elizabeth is persuaded to spare her son from execution.

Sonnet 49

Against that time (if ever that time come)

When I shall see thee frown on my defects,

When as thy love hath cast his utmost sum,

Called to that audit by advised respects;

Against that time when thou shalt strangely pass,

And scarcely greet me with that sunne thine eye;

When love converted from the thing it was

Shall reasons find of settled gravity;

Against that time do I ensconce me here,

Within the knowledge of mine own desert,

And this my hand against myself uprear,

To guard the lawful reasons on thy part:

To leave poor me, thou hast the strength of laws,

Since why to love, I can allege no cause.

1 AGAINST THAT TIME (IF EVER THAT TIME COME)

AGAINST THAT TIME = in anticipation of; fortifying for; EVER = E. Ver, Edward de Vere

2 WHEN I SHALL SEE THEE FROWN ON MY DEFECTS,

FROWN = the royal frown of his son, a prince; “Great Princes’ favorites their fair leaves spread,/ But as the Marigold at the sun’s eye,/ And in themselves their pride lies buried,/ For at a frown they in their glory die” – Sonnet 25, lines 5-8

MY DEFECTS = my inability to have made you king; defection from my purpose for you; (“The king … made a defect from his purpose” – OED, 1540; the word “defect” was “used like Latin defectus to mean ‘eclipse,’ ‘failure (of a heavenly body) to shine” – Booth); “That thou art blamed shall not be thy defect” – Sonnet 70, line 1, to his son; “When all my best doth worship thy defect,/ Commanded by the motion of thine eyes” – Sonnet 149, lines 11-12, to Queen Elizabeth, who commands with her imperial eyes or viewpoint and condemns with her frown; “Our will became the servant to defect” – Macbeth, 2.1.18

3 WHEN AS THY LOVE HATH CAST HIS UTMOST SUM,

THY LOVE = your royal blood; HATH CAST HIS UTMOST SUM = has reached its final accounting, with the determination as to whether you are to be a King of England; “has closed his account and cast up the sum total” – Dowden; “Profitless usurer, why dost thou use/ So great a sum of sums yet canst not live?” – Sonnet 4, lines 7-8, i.e., his abundant royal blood and right to claim to the throne; “To leave for nothing all thy sum of good” – Sonnet 109, line 12

4 CALLED TO THAT AUDIT BY ADVISED RESPECTS;

AUDIT = final accounting; “Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,/ What acceptable Audit canst thou leave?” – Sonnet 4, lines 11-12; “Her Audit (though delayed) answered must be,/ And her Quietus is to render thee” – Sonnet 126, lines 11-12

ADVISED RESPECTS = “Marks of deference for high rank” – Booth, citing Willen & Reed; “Deliberate, well-considered reasons” – Dowden;

The King:

And on the winking of authority

To understand a law, to know the meaning

Of dangerous majesty, when perchance it frowns

More upon humour than advised respect.

Hubert:

Here is your hand and seal for what I did.

The King:

O, when the last accompt ‘twixt heaven and earth

Is to be made, then shall this hand and seal

Witness against us to damnation!

– King John, 4.2.211-218

5 AGAINST THAT TIME WHEN THOU SHALT STRANGELY PASS

AGAINST THAT TIME = (see line 1 above); STRANGELY PASS = walk by without acknowledging me, i.e., specifically without acknowledging me as your father; go past me as a stranger; (“I will acquaintance strangle and look strange” – Sonnet 89)

6 AND SCARCELY GREET ME WITH THAT SUNNE THINE EYE,

THAT SUNNE THINE EYE = that royal eye of yours, which is a star or sun; (“Seek the King. That sun, I pray, may never set” – Henry VIII, 3.2.414); “Full many a glorious morning have I seen/ Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye” – Sonnet 33, lines 1-2, when Oxford goes on to describe the birth of his royal son: “Even so my Sunne one early morn did shine” – line 9; “Lo in the Orient when the gracious light/ Lifts up his burning head, each under eye/ Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,/ Serving with looks his sacred majesty” – Sonnet 6, lines 1-4; “For as the Sun is daily new and old,/ So is my love still telling what is told” – Sonnet 76, lines 13-14, linking his royal son with “the sun” and “my love”; “Making a couplement of proud compare/ With Sunne and Moon” – Sonnet 21, lines 5-6, speaking of Southampton, the royal son, and Elizabeth, goddess of the Moon, as son and mother; “And truly not the morning Sun of Heaven” – Sonnet 132, line 5; “Roses have thorns, and silver fountains mud,/ Clouds and eclipses stain both Moone and Sunne” – Sonnet 35, lines 2-3; i.e., Elizabeth and her royal son (whose eye is a sun) are being eclipsed in terms of the inability of their Tudor Rose blood to continue on the throne: “Crooked eclipses ‘gainst his glory fight” – Sonnet 60, line 7; glancing at the hunched or crooked back of Robert Cecil, who has “eclipsed his glory.”

Robert Cecil had orchestrated the trial of Essex and Southampton, a travesty of justice that led to a unanimous verdict of guilt - high treason - and a sentence of death "at her Majesty's pleasure"

7 WHEN LOVE CONVERTED FROM THE THING IT WAS

LOVE = your royal blood; when royal blood, transformed from its golden time of hope for your succession to the throne; CONVERTED = a nod to Ver, E. Ver (“conVerted”) and as the “gaudy spring” (“Ver” in French) of Sonnet 1; turned away from, as the sun might turn from the planets and no longer shine

8 SHALL REASONS FIND OF SETTLED GRAVITY;

REASONS = echoing legal arguments; related to equity, fairness, justice; (see line 12); SETTLED GRAVITY = sober judgment; related to the grave; when your royal blood is converted from its right to the throne, for legal reasons that are agreed upon by those in power, with my help and consent

9 AGAINST THAT TIME DO I ENSCONCE ME HERE

AGAINST THAT TIME = (the third usage in this verse); ENSCONCE ME = fortify myself, as you are ensconced within the fortress of the Tower; “protect or cover as with a sconce or fort” – Dyce, cited by Dowden

10 WITHIN THE KNOWLEDGE OF MINE OWN DESERT,

Within the knowledge of the truth, i.e., of my fatherhood of you; knowing what I deserve as the father of a king; MINE OWN = related to his own son; “a son of mine own” – Oxford to Burghley, March 17, 1575; Sonnets 23, 39, 49, 61, 62, 72, 88, 107, 110; DESERT = “Who will believe my verse in time to come/ If it were filled with your most high deserts?” – Sonnet 17, line 1-2; in this case Oxford’s desert is his fatherhood, which he has only within his “knowledge” of it, but not in reality.

MINE OWN:

I am Launcelot, your boy that was, your son that is, your child that shall be…I’ll be sworn if thou be Launcelot, thou art mine own flesh and blood

– Merchant of Venice, 2.2.80-88

11 AND THIS MY HAND AGAINST MYSELF UPREAR

And for this I raise up my hand in court to testify against myself; go against my own guilty verdict at the trial; but more importantly, according to the bargain to save Southampton’s life, his willingness to raise his hand as witness to the lie that must be perpetrated, i.e., to pretend that Southampton should not be king; (by the same token, Oxford’s son must be a “suborned informer” against his own truth: “Hence, thou suborned Informer, a true soul/ When most impeached stands least in thy control” – Sonnet 125, lines 13-14, the final words to Southampton before the farewell envoy of Sonnet 126, ending the dynastic diary); HAND = “If this right hand would buy but two hours’ life” – 3 Henry VI, 2.6.80; “Or what strong hand can hold his (Time’s) swift book back” – Sonnet 65, the final verse before word arrives that Southampton’s life has been spared

12 TO GUARD THE LAWFUL REASONS ON THY PART.

To protect the legal reasons being put forth in order to save your life (the forthcoming answer is “misprision” of treason, Sonnet 87, line 11); GUARD = echoing the prison guards at the Tower; “To guard a title that was rich before” – King John, 4.2.10; “Ay, wherefore else guard we his royal tent but to defend his person from night-foes?” – 3 Henry VI, 4.3.21-22

l

Queen Elizabeth I had been trapped by her own image as the Virgin Queen

LAWFUL = “Let it be lawful” – King John, 3.1.112; “Edward’s son, the first-begotten, and the lawful heir of Edward king” – 1 Henry VI, 2.5.64-66; “And ‘gainst myself a lawful plea commence” – Sonnet 35, line 11; “lawful = rightful, legitimate” – Schmidt; “lays most lawful claim to this fair island and the territories” – King John, 1.1.9-10; “That thou hast underwrought his lawful king, cut off the sequence of posterity” – King John, 2.1.95-96

REASONS = playing off “reasons” in line 8; “And yet his trespass, in our common reason … is not, almost, a fault” – Othello, 3.3.64-66; ON THY PART = on your side, legally, to save you from the consequences of your treason, trespass, fault

13 TO LEAVE POOR ME THOU HAST THE STRENGTH OF LAWS,

TO LEAVE POOR ME = to separate from me as my son, leaving me empty; “Suppose by right and equity thou be king, think’st thou that I will leave my kingly throne, wherein my grandsire and my father sat?” – 1 Henry VI, 1.1.127-129

THOU HAST THE STRENGTH OF LAWS = you have a legal basis upon which to be saved, but that bargain forces you to abandon your claim to the throne; STRENGTH = royal power, Elizabeth’s and your own; “If thou wouldst use the strength of all thy state” – Sonnet 96, line 12; strength of legal argument on your behalf; “And strength by limping sway disabled” – Sonnet 66, line 8, referring to the limping, swaying Robert Cecil, Secretary of State, who disabled Southampton’s royal power; “In the very refuse of thy deeds/ There is such strength and warranties of skill” – Sonnet 150, lines 6-7, to Elizabeth as absolute monarch with royal power and authority

14 SINCE WHY TO LOVE I CAN ALLEGE NO CAUSE.

Since I cannot testify to why I love you; because I cannot reveal you are my son by the Queen; ALLEGE = echoing the allegations at the trial; CAUSE = motive, i.e., as your father (“allege” and “cause” are both legal terms; a “cause” is an adequate ground for action, as in “upon good cause shown to the court” – Tucker); “The cause of this fair gift in me is wanting,/ And so my patent back again is swerving” – Sonnet 87, lines 7-8; “The more I hear and see just cause of hate” – Sonnet 150, line 10

Published in: Uncategorized

on November 2, 2009 at 11:49 pm

Comments (2)

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, legal terms, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, Shakespeare, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 49, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, legal terms, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, Shakespeare, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 49, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“Locked Up” – Southampton in the Tower – “The Living Record” – Chapter 45

Here is my entry for Sonnet 48 in THE MONUMENT:

DAY TWENTY-TWO IN THE TOWER

“Locked Up”

1 March 1601

THE MONUMENT by Hank Whittemore

While working to save his son’s life, Oxford is concerned that other conspirators inside the prison are urging his royal son (Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton) to further revolt before the Crown has a chance to execute him.

Sonnet 48

How careful was I, when I took my way,

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust,

That to my use it might unused stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust?

But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are,

Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief,

Thou best of dearest, and mine only care,

Art left the prey of every vulgar thief.

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part;

And even thence thou wilt be stol’n, I fear;

For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear.

1 HOW CAREFUL WAS I WHEN I TOOK MY WAY,

CAREFUL = echoed by “care” in line 7; TOOK MY WAY = set out on the journey of my life; also, set out to write these sonnets to record my son’s royal progress in relation to the dwindling time of Elizabeth’s life; MY WAY = “Were I a man, a duke, and next of blood, I would remove these tedious stumbling-blocks and smooth my way upon their headless necks” – 2 Henry VI, 1.2.63-65; “Torment myself to catch the English crown: And from that torment I will free myself, or hew my way out with a bloody axe” – 3 Henry VI, 3.2.179-181; “I am amazed, methinks, and lose my way among the thorns and dangers of this world” – King John, 4.3.140-141

2 EACH TRIFLE UNDER TRUEST BARS TO THRUST,

EACH TRIFLE = each piece of writing (precious jewels or rings or tokens of bond: “And sweetest, fairest, as I my poor self did exchange for you to your so infinite loss; so in our trifles I still win of you” – Cymbeline, 1.2.49-52); TRUEST = Oxford’s motto (Nothing Truer than Truth); TRUEST BARS = (“most reliable locks or barricades” – Duncan-Jones); also, the image of the BARS or locks and barricades of the Tower, where Southampton is a prisoner; “Through a secret grate of iron bars in yonder Tower” – 1 Henry VI, 1.4.10-11; TO THRUST = the image of Oxford hiding his written work; also in these lines, Oxford may be referring to the care he took to keep his royal son hidden from view, protected from plots and so on.

3 THAT TO MY USE IT MIGHT UN-USED STAY

STAY = remain under lock and key; be kept away from; “where thou dost stay” – Sonnet 44, line 4; also suggesting the hope for a “stay of execution”; “Retreat is made and execution stay’d” – 2 Henry IV, 4.3.72

4 FROM HANDS OF FALSEHOOD, IN SURE WARDS OF TRUST?

FROM HANDS OF FALSEHOOD = away from those who are “untrue” or who do not wish the truth ever to be written; from thieves or other conspirators; also the hands or hand of Elizabeth, who is also Time; “And by their hands this grace of kings must die, if hell and treason hold their promises” – Henry V, 2.0.Chorus.28-29; “With time’s injurious hand crushed and o’erworn” – Sonnet 63, line 2; “When I have seen by time’s fell hand defaced” – Sonnet 64, line 1; “Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?” – Sonnet 65, line 11; “And almost thence my nature is subdued,/ To what it works in, like the Dyer’s hand” – Sonnet 111, lines 6-7; “For since each hand hath put on Nature’s power” – Sonnet 127, line 5; “Was sleeping by a Virgin hand disarmed” – Sonnet 154, line 8, the latter in reference to Elizabeth, the so-called Virgin Queen, refusing to acknowledge her newborn son in 1574; FALSEHOOD = “The usual adverbs in legal records alongside the descriptions of particular treasons are ‘falsely’ and ‘traitorously’” – Bellamy, Tudor Law of Treason, p. 33; hands of falsehood = hands of traitors; WARDS = “Meaning ‘guards’ and used to describe places that can be locked for safekeeping; the range of its applications includes chests and prison cells” – Booth; “I am come to survey the Tower this day … where be these warders … Open the gates” – 1 Henry VI, 1.3.1-3; “prison … in which there are many confines, wards, and dungeons” – Hamlet, 2.2.260,262-263; prison guards; the “wards” of a lock; OF TRUST = of those who can be trusted

5 BUT THOU, TO WHOM MY JEWELS TRIFLES ARE,

BUT THOU = but you; TO WHOM = compared to whom; MY JEWELS = my writings, i.e., these private verses, which all involve Southampton, a prince who was “the world’s fresh ornament” in Sonnet 1 or the “jewel” whose life is being recorded here; “As for my sons, say I account of them as jewels” – Titus Andronicus, 3.1.198-199; “Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,/ Which like a jewel hung in ghastly night” – Sonnet 27, lines 10-11; “As on the finger of a throned Queen,/ The basest Jewel will be well esteemed” – Sonnet 96, lines 5-6

6 MOST WORTHY COMFORT, NOW MY GREATEST GRIEF,

MOST WORTHY = most royal or kingly; “a king of so much worth” – 1 Henry VI, 1.1. 7; “Most worthy brother England” – the King of France addressing Henry V of England, Henry V, 5.2.10; “That were I crown’d the most imperial monarch, thereof most worthy” – The Winter’s Tale, 4.4.374-375; “Most worthy prince” – Cymbeline, 5.5.359; COMFORT = “Warwick, my son, the comfort of my age” – 2 Henry VI, 1.1.189; “O my good lord, that comfort comes too late; ‘tis like a pardon after execution” – Henry VIII, 4.2.120-121; “As a decrepit father takes delight/ To see his active child do deeds of youth,/ So I, made lame by Fortune’s dearest spite,/ Take all my comfort of thy worth and truth” – Sonnet 37, lines 1-4; NOW MY GREATEST GRIEF = now you are the cause of the greatest grief in my life; “To me and to the state of my great grief let kings assemble; for my grief’s so great” – King John, 2.2.70-71; “Let every word weigh heavy of her worth that he does weigh too light: my greatest grief, though little do he feel it, set down sharply” – All’s Well That Ends Well, 3.4.31-33

This Sessions, to our great grief we pronounce The Winter’s Tale, 3.2.

(The king opens the Sessions or Treason Trial)

7 THOU BEST OF DEAREST, AND MINE ONLY CARE,

THOU BEST OF DEAREST = you, most royal of most royal, dear son; “My dear dear lord … dear my liege” – Richard II, 1.1.176, 184); BEST = “Richard hath best deserv’d of all my sons” – 3 Henry VI, 1.1.18; DEAREST = “Thou would’st have left thy dearest heart-blood there, rather than made that savage duke thine heir, and disinherited thine only son” – 3 Henry VI, 1.1.229-231; “And take deep traitors for thy dearest friends” – Richard III, 1.3.224

Too familiar is my dear son with such sour company

Romeo and Juliet, 3.3.7-8

ONLY = the “one” of Southampton’s motto; supreme; he is the “onlie begetter” of the 1609 dedication of the Sonnets; he was the “only herald to the gaudy spring” of Sonnet 1

MINE ONLY = “Ah, no, no, no, it is mine only son!” – 3 Henry VI, 2.5.83; “His name is Lucentio and he is mine only son” – The Taming of the Shrew, 5.1.77-78

O me, O me! My child, my only life

Romeo and Juliet, 4.5.19

MINE ONLY CARE = Southampton, my only concern; CARE = Bolinbroke: “Part of your cares you give me with your crown”; King Richard: “Your cares set up do not puck my cares down. My care is loss of care, by old care done; your care is gain of care, by new care won. The cares I give, I have, though given away, they ‘tend the crown, yet still with me they stay” – Richard II, 4.1.194-199

8 ART LEFT THE PREY OF EVERY VULGAR THIEF.

Are left in the Tower for every common thief to harm or steal; EVERY VULGAR THIEF = a passing glance at himself as E. Ver, Edward de Vere, who tries to steal looks at his son; every common or base criminal in the Tower with you, urging you to further rebellion

Southampton in the Tower

9 THEE I HAVE NOT LOCKED UP IN ANY CHEST,

LOCKED UP = It is not I who have locked you up in the Tower or anywhere else; “Lock up my doors” – The Merchant of Venice, 2.5.29; “You’re my prisoner, but your gaoler shall deliver the keys that lock up your restraint” – Cymbeline, 1.2.3-5

For treason is but trusted like the fox,

Who, never so tame, so cherished and locked up 1 Henry IV, 5.2.9-10

So am I as the rich whose blessed key

Can bring him to his sweet up-locked treasure Sonnet 52, lines 1-2

CHEST = coffer for valuables or jewels; IN ANY CHEST = in any prison; “A jewel in a ten-times-barr’d-up chest is a bold spirit in a loyal breast” – Richard II, 1.1.180-181; (to Southampton in the Sonnets as “ornament” or “jewel” or royal prince who is imprisoned and whose truth is hidden: “So is the time that keeps you as my chest” – Sonnet 52, line 9; “Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?” – Sonnet 65, line 10); “I thought myself to commit an unpardonable error to have murdered the same in waste-bottoms of my chests” – Oxford’s Prefatory Letter to Cardanus’ Comfort, 1573

10 SAVE WHERE THOU ART NOT, THOUGH I FEEL THOU ART

Except where you are not, i.e., except outside the high fortress walls, where you are free (in my mind and heart, within my breast)

11 WITHIN THE GENTLE CLOSURE OF MY BREAST,

GENTLE = suited for royalty; tender; CLOSURE = enclosure; the only place I keep you; i.e., the more loving “closure” of his breast or heart, as opposed to the fortress walls of the Tower prison where Southampton is confined:

O Pomfret, Pomfret! O thou bloody prison,

Fatal and ominous to noble peers!

Within the guilty closure of thy walls

Richard the Second here was hack’d to death! Richard III, 3.3.9-12

To Elizabeth about their son, contrasting the gentleness of his “jail” with the harshness or rigor of her Tower: “Prison my heart in thy steel bosom’s ward,/ But then my friend’s heart let my poor heart bail;/ Who ere keeps me, let my heart be his guard,/ Thou canst not then use rigor in my jail” – Sonnet 133, lines 9-12

Queen Elizabeth I never lifted a finger to help Southampton, who remained in the Tower until she died and King James succeeded her

12 FROM WHENCE AT PLEASURE THOU MAYST COME AND PART.

AT PLEASURE = at Your Majesty’s pleasure; at his royal son’s command; “She flatly said whether it were mine or hers she would bestow it at her pleasure” – Oxford to Robert Cecil, October 20, 1595, in reference to the Queen; THOU MAYST COME AND PART = you may come and go

13 AND EVEN THENCE THOU WILT BE STOL’N, I FEAR,

Even then I fear you will be stolen from me; THOU WILT BE STOL’N, I FEAR = “Thou hast stol’n that which after some few hours were thine without offence” – the king to his royal son, referring to the crown, in 1 Henry IV, 4.5.101-102; “And buds of marjoram had stol’n thy hair” – Sonnet 99, line 7, playing on “heir”

14 FOR TRUTH PROVES THIEVISH FOR A PRIZE SO DEAR.

TRUTH = Oxford, Nothing Truer than Truth; “your true rights” – Sonnet 17, line 11; FOR TRUTH PROVES THIEVISH FOR A PRIZE SO DEAR = because the truth, that you are a prince, proves a prize for those “thieves” who want to rebel against the Crown and put you on the throne; for even I, Oxford, might become a thief to steal you, my dear son, who are so royal a prize; (“The prey entices the thief” – Tilley, P570, adapted in Venus and Adonis: “Rich preys make true men thieves” – line 724); Southampton, having a claim to the throne, is indeed “a prize so dear” or so royal, with “dear” as in “my dear royal son”; “If my dear love were but the child of state,/ It might for fortune’s bastard be un-fathered” – Sonnet 124, lines 1-2

Published in: Uncategorized

on October 22, 2009 at 2:13 am

Comments (2)

Tags: authorship, confined doom, dark lady, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, legal terms, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shake-speare's treason, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, sonnet 48, sonnets, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, confined doom, dark lady, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, legal terms, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shake-speare's treason, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, sonnet 48, sonnets, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

A Bargain for Southampton’s Life – “The Living Record” – Chapter 44

Sonnet 47 – February 28, 1601

Three days after the execution of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, this sonnet resolves the struggle between Oxford’s eye (mind) and heart (emotions) described in the previous verse — the struggle between his duty to the state, having to vote for a guilty verdict against both Essex and Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton … and then to work behind the scenes for the latter, his son by the Queen, in order to hopefully save his life.

The Earl of Essex, beheaded at the Tower Green on February 25, 1601

Oxford records that a “league” or bargain with Secretary Robert Cecil has been struck in order to spare Southampton from execution. The ransom price, however, will be Southampton’s relinquishment of any claim to the throne. Meanwhile Oxford writes to record again that the image of his imprisoned royal son is always with him:\

Betwixt mine eye and heart a league is took,

(“You peers, continue this united league” – Richard III, 2.1.2)

And each doth good turns now unto the other;

When that mine eye is famished for a look,

Or heart in love with sighs himself doth smother,

With my love’s picture then my eye doth feast,

And to the painted banquet bids my heart:

An other time mine eye is my heart’s guest,

And in his thoughts of love doth share a part.

(“The pleasure that some fathers feed upon is my strict fast – I mean my children’s looks, and therein fasting hast thou made me gaunt” – Richard II, 2.1.79-81; “And so my state … show’d like a feast” – the king in 1 Henry IV, 3.2.53-59)

So either by thy picture or my love,

Thy self away, art present still with me:

For thou no further than my thoughts canst move,

And I am still with them, and they with thee;

Or if they sleep, thy picture in my sight

Awakes my heart to heart’s and eye’s delight.

Are these sonnets referring to Southampton being “away” in the Tower? Look at these references:

“Things removed” – Sonnet 31, line 8

“O absence” – Sonnet 39, line 9

“When I am sometime absent from thy heart” – Sonnet 41, line 2

“Where thou art” – Sonnet 41, line 12

“Injurious distance” – Sonnet 44, line 1

“Where thou dost stay” – Sonnet 44, line 4

“Removed from thee” – Sonnet 44, line 6

“Present-absent” – Sonnet 45, line 4

“Where thou art” – Sonnet 51, line 3

“The bitterness of absence” – Sonnet 57, line 6

“Where you may be” – Sonnet 57, line 10

“Where you are” – Sonnet 57, line 12

“The imprisoned absence of your liberty” – Sonnet 58, line 6

“Where you list” – Sonnet 58, line 9

“Thou dost wake elsewhere” – Sonnet 61, line 12

“All away” – Sonnet 75, line 14

“Be absent from thy walks” – Sonnet 89, line 9

“How like a Winter hath my absence been/ From thee” – Sonnet 97, line 1

“This time removed” – Sonnet 97, line 5

“And thou away” – Sonnet 97, line 12

“You away” – Sonnet 98, line 13

King James VI of Scotland, for whom Robert Cecil is now working, behind Queen Elizabeth's back, in order to engineer his succession (with Southampton being held hostage in the Tower until James can be proclaimed King of England)

To be continued…

Published in: Uncategorized

on October 12, 2009 at 2:12 am

Comments (2)

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, James VI of Scotland, King James, legal terms, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, robert devereux, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 107, sonnet 47, sonnets, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, James VI of Scotland, King James, legal terms, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, robert devereux, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 107, sonnet 47, sonnets, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“Building the Case for Edward de Vere as Shakespeare” – The Complete Tables of Contents Vols 1 – 5

Here are all Tables of Contents for the first five volumes of

BUILDING THE CASE FOR EDWARD DE VERE AS SHAKESPEARE

Series Editors: Paul Altrocchi & Hank Whittemore

NOW AVAILABLE AT

iUniverse Publishing (800-288-4677 x 5024)

iuniverse.com … amazon.com (search by volume title)

VOLUME 1: THE GREAT SHAKESPEARE HOAX

After Unmasking the Fraudulent Pretender,

Search for the True Genius Begins

Part 1: Growing Disbelief in the Stratford Man as Shakespeare

1. Preface

2. Elsie Greenwood: Obituary of G. G. Greenwood [1859-1928]

3. George Greenwood, 1916: Is There A Shakespeare Problem?

4. George Greenwood, 1916: Professor Dryasdust and “Genius”

5. George Greenwood, 1916: The Portraits of Shakespeare

6. George Greenwood, 1916: Shakespeare as a Lawyer

7. George Greenwood, 1921: Ben Jonson and Shakespeare

8. George Greenwood, 1925: Stratford Bust and the Droeshout

Part 2: The Breadth of Shakespeare’s Knowledge

1. Preface

2. James Harting, 1864: Ornithology of Shakespeare

3. Archibald Geikie, 1916: The Birds of Shakespeare

4. William Theobald, 1909: The Classical Element in the Shakespeare Plays.

5. Cumberland Clark, 1922: Astronomy in the Poets

6. St. ClairThomson, 1916: Shakespeare and Medicine

7. Eva Turner Clark, 1931: Singleton’s The Shakespeare Garden

8. C. Clark, 1929: Shakespeare and Science, including Astronomy

9. Richard Noble, 1935: Shakespeare’s Biblical Knowledge

Part 3: The Case for Francis Bacon

1. Preface

2. H. Crouch Batchelor, 1912: Advice to English Schoolboys

3. Georges Connes, 1927: The Shakespeare Mystery

4. J. Churton Collins, 1904: Studies in Shakespeare

5. Roderick Eagle, 1930: Shakespeare. New Views for Old

6. Harold Bayley, 1902: The Tragedy of Sir Francis Bacon

7. George Bompas, 1902: The Problem of Shakespeare Plays

8. Elizabeth Wells Gallup, 1910: The Bi-lateral Cipher of Sir Francis Bacon.

9. John H. Stotsenburg, 1904: An Impartial Study of the Shakespeare Title.

10. Granville Cuningham, 1911: Bacon’s Secrets Disclosed in Contemporary Books

11. Gilbert Slater, 1931: Seven Shakespeares

Part 4: Edward de Vere Bursts out of Anonymity

1. Preface

2. V. A. Demant, 1962: Obituary of J. Thomas Looney [1870-1944]

3. J. Thomas Looney, 1920: “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford

Part 5: A Sudden Eruption of Oxfordian Giants

1. Preface

2. Marjorie Bowen, 1933: Introduction to Percy Allen’s The Plays of Shakespeare and Chapman in Relation to French History

3. Obituary of Hubert Henry Holland [1873-1957]

4. Hubert H. Holland, 1923: Shakespeare through Oxford Glasses

5. Phyllis Carrington, 1962: Obituary of Bernard Rowland Ward

6. Colonel B. R. Ward, 1923: The Mystery of “Mr. W. H.”

7. Obituary of Bernard Mordaunt Ward [1893-1943]

8. B. M. Ward, 1928: The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford

9. Obituary of Mrs. Eva Turner Clark [1871-1947]

10. Eva Turner Clark, 1931: Hidden Allusions in Shakespeare’s Plays

11. Rev. Gerald Rendall, 1930: Shakespeare’s Sonnets

12. T. L. Adamson, 1959: Obituary of Percy AlIen [1875-1959]

13. Percy Allen, 1933: The Plays of Shakespeare and Chapman in Relation to French History

14. Percy Allen, 1930: The Case for Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford as “Shakespeare”

15. Percy Allen, 1931: The Oxford-Shakespeare Case Corroborated

16. F. Lingard Ranson, 1940: Death of Ernest Allen [1875-1940]

17. Percy Allen and Ernest Allen, 1933: Lord Oxford and “Shakespeare”: A Reply to John Drinkwater

VOLUME 2: NOTHING TRUER THAN TRUTH

Fact versus Fiction in the

Shakespeare Authorship Debate

Part 1: Authorship Articles from England in the 1930s

1. Preface

2. Percy Allen, 1937: Lord Oxford as Shakespeare

3. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1938: The Man Who Was Shakespeare by Eva Turner Clark

4. J. Thomas Looney, 1935: Lord Oxford and the Shrew Plays, Part 1

5. J. Thomas Looney, 1935: Lord Oxford and the Shrew Plays, Part 2

6. Gilbert Slater, 1934: Letter to Editor

7. Canon Gerald Rendall, 1935: Lord Oxford was “Shakespeare” by Montague Douglas

8. Editors, 1935: Elizabeth Trentham and Edward deVere

9. Ernest Allen, 1937: Shakespeare’s Sonnets

10. Bernard M. Ward, 1937: Shakespearean Notes

11. Bernard M. Ward, 1937: When Shakespeare Died by Ernest Allen

12. F. Lingard Ranson, 1937: Shakespeare: An East Anglian

13. Percy Allen, 1938: The De Vere Star

14. Editor, 1940: Ben Jonson and the First Folio by G. H. Rendall

15. Montague Douglas, 1940: Welcome to the American Branch

Part 2: Shakespeare Fellowship News-Letters from the American Branch, 1939-1943

1. Preface

2. Eva Turner Clark, 1939: Introduction to the ShakespeareFellowship, American Branch

3. Louis Benezet, 1939: The President’s Message

4. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1939: To Pluck the Heart of the Mystery

5. Editors, 1939: Origins and Achievements of the Shakespeare Fellowship

6. Editors, 1939: Noted Oxfordian Ernest Allen Dies

7. Editors, 1940: Scientific Proof that certain Shakesper Portraits are De Vere

8. Editors, 1940: Dean of Literary Detectives on the War

9. Louis Benezet, 1940: Organization of the Shakespeare Fellowship, American Branch

10. Eva Turner Clark, 1940: Shakespeare Read Books Written in Greek

11. Eva Turner Clark, 1940: Shakespeare’s Birthday

12. Editors, 1940: Editorial in The Argonaut of San Francisco

13. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1940: Mountainous Error

14. Eva Turner Clark, 1940: The Date of Hamlet’s Composition

15. Louis Benezet, 1940: Shakespeare and Ben Jonson

16. Editors, 1940: A Master of Double-Talk

17. Eva Turner Clark, 1940: He Must Build Churches Then

18. Esther Singleton, 1940: Was Edward de Vere Shakespeare?

19. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1940: Dr. Phelps and his Muddled Miracle

20. EvaTurner Clark, 1940: The Painting in Lucrece

21. Charles Wisner BarreD, 1940: Arthur Golding and Edward de Vere

22. Eva Turner Clark, 1940: Topicalities in the Plays

23. Eva Turner Clark, 1940: Anomos, or A. W.

24. Eva Turner Clark, 1940: Gabriel Harvey and Axiophilus

25. J. Thomas Looney, 1941:”Shakespeare”: A Missing Author, Part 1

26. J. Thomas Looney, 1941: “Shakespeare”: A Missing Author, Part 2

27. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1941: Shakespeare’s Irish Sympathies

28. Louis Benezet, 1941: A 19th Century Revolt against the Stratford Theory, Part 1

29. Louis Benezet, 1941: The Great Debate of 1892-1893: Bacon vs. Shakespeare, Part 2

30. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1941: Shakespeare’s “Fluellen” Identified as a Retainer of the Earl of Oxford

31. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1941: “Shake-speare’s” Own Secret Drama, Pt 1

32. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1941: “Shake-speare’s” Own Secret Drama, Pt 2

33. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1942: “Shake-speare’s” Own Secret Drama, Pt 3

34. Editors, 1942: Import of These Discoveries

35. Flodden W. Heron, 1942: Bacon Was Not Shakespeare

36. Eva Turner Clark, 1942: Lord Oxford as Shakespeare

37. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1942: “Shake-speare’s” Own Secret Drama, Pt 4

38. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1942: “Shake-speare’s” Own Secret Drama, Pt 5

39. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1942: “Shake-speare’s” Own Secret Drama, Pt 6

40. Louis Benezet, 1942: Shaksper, Shakespeare, and DeVere

41. Eva Turner Clark, 1942: The Red Rose

42. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1942: “Shake-speare’s” Unknown Home on the Avon

43. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1943: He Is Dead and Gone, Lady

44. Louis Benezet, 1943: Look at the Chronicles, Part 1

45. Louis Benezet, 1943: Look at the Chronicles, Part 2

46. Louis Benezet, 1943: Look in the Chronicles, Part 3

47. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1943: King of Shreds and Patches – Dyer as “Great Revisor” of the Shakespearean Works

48. Phyllis Carrington, 1943: Was Lord Oxford Buried in Westminster Abbey?

49. Editors, 1943: The Duke of Portland’s Welbeck Portrait

50. Eva Turner Clark, 1943: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres

51. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1943: Who Was John Soothern?

52. Eva Turner Clark, 1943: Cryptic Passages by Davies of Hereford

53. George Frisbee, 1943: Shame on the Professors

VOLUME 3: SHINE FORTH

Evidence Grows Rapidly in Favor of

Edward de Vere as Shakespeare

Part 1: Articles from the Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly (1943-1947)

1. Preface

2. Editors, 1943: The Quarterly, A Continuation of the News-Letter

3. Louis Benezet, 1944: The Frauds and Stealths of Injurious Impostors

4. Eva Turner Clark, 1944: Stolen and Surreptitious Copies

5. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1944: Documentary Notes on the Swan Theatre

6. Editors, 1944: Obituary of John Thomas Looney [1870-1944]

7. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1944: Newly Discovered Oxford- Shakespeare Pictorial Evidence

8. Eva Turner Clark, 1944: Some Character Names in Shakespeare’s Plays. Part 1

9. Eva Turner Clark, 1944: Some Character Names in Shakespeare’s Plays. Part 2

10. Eva Turner Clark, 1944: Some Character Names in Shakespeare’s Plays. Part 3

11. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1944: Lord Oxford as Supervising Patron of Shakespeare’s Theatrical Company

12. Louis Benezet, 1944: The Stratford Defendant Compromised His Own Advocates. Part 1

13. Louis Benezet, 1944: The Stratford Defendant Compromised His Own Advocates. Part 2

14. Louis Benezet, 1944: The Stratford Defendant Compromised His Own Advocates. Part 3

15. Louis Benezet, 1944: The Stratford Defendant Compromised His Own Advocates. Part 4

16. Louis Benezet, 1944: The Authorship of Othello

17. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1944: New Milestone in Shakespearean Research: “Gentle Master William”

18. Eva Turner Clark, 1945: Lord Oxford’s Shakespearean Travels

19. Charles W. Barrell, 1945: “The Sole Author of Renowned Victorie.” Gabriel Harvey Testifies in the Oxford-Shakespeare Case

20. Charles Wisner Barreil, 1945: Earliest Authenticated “Shakespeare” Transcript Found With Oxford’s Personal Poems

21. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1945: Rare Military Volume Sponsored by Lord Oxford Issued by “Shakespeare’s” First Publisher

22. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1945: The Wayward Water-Bearer Who Wrote “Shake-speare’s” Sonnet 109

23. Eva Turner Clark, 1945: Lord Oxford’s Letters Echoed in Shakespeare’s Plays. An Early Letter Examined. Part 1

24. Eva Turner Clark, 1945: Lord Oxford’s Letters Echoed in Shakespeare’s Plays. An Early Letter Examined. Part 2

25. Louis Benezet, 1945: The Remarkable Testimony of Henry Peacham.

26. Charles W. Barrell, 1945: “Creature of Their Own Creating.” An Answer to the Present School of Shakespeare Biography

27. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1945: Genesis of a Henry James Story

28. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1946: Exploding the Ancient Play Cobbler Fantasy

29. Lewis Hammond Webster, 1946: Those Authorities

30. Louis Benezet, 1946: Another Stratfordian Aids the Oxford Cause.

31. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1946: A Literary Pirate’s Attempt to Publish The Winter’s Tale in 1594

32. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1946: The Playwright Earl Publishes “Hamlet’s Book”

33. Louis Benezet, 1946: False Shakespeare Chronology Regarding the Date of King Henry VIII

34. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1946: Shakespeare’s Henry V Can Be Identified as Harry of Cornwall in Henslowe’s Diary

35, Eva Turner Clark, 1946: Shakespeare’s Strange Silence When James I Succeeded Elizabeth

36. Charles W. Barrell, 1946: Proof That Shakespeare’s Thought and Imagery Dominate Oxford’s Statement of Creative Principles

37. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1947: Queen Elizabeth’s Master Showman Shakes a Spear in Her Defense

38. James J. Dwyer, 1947: The Poet Earl of Oxford and Grays Inn

39. Louis Benezet, 1947: Dr. Smart’s Man of Stratford Outsmarts Credulity

40. Editors, 1947: Sir George Greenwood

41. Editors, 1947: Physician, Heal Thyself

Part 2: Bonus Selections

1. Preface

2. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1937: Elizabethan Mystery Man

3. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1940: Shakespearean Detective Story

4. Percy Allen & B.M. Ward, 1936: Relations between Lord Oxford as “Shakespeare,” Queen Elizabeth and the Fair Youth. Part 1

5. Percy Allen & B.M. Ward, 1936: Relations between Lord Oxford as “Shakespeare,” Queen Elizabeth and the Fair Youth. Part 2

VOLUME 4: MY NAME BE BURIED

A Coerced Pen Name Forces the

Real Shakespeare into Anonymity

Part 1: Articles from The Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly, 1947-1948

1. Preface

2. Louis Benezet, 1947: The Shakespeare Hoax: An Improbable Narrative

3. Editors, 1947: Tufts College Then and Now

4. Abraham Feldman, 1947: Shakespeare’s Jester: Oxford’s Servant

5. Editors, 1947: Revising Some Details of an Important Discovery in Oxford-Shakespeare Research: Peacham’s Minerva Britanna

6. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1947: Pictorial Clues and Key Initials

7. Editors, 1947: Historical Background of The Merchant of Venice Clarified

8. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1947: New Proof that Henry Vlll was Written Before the spring of 1606

9. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1947: Dr. John Dover Wilson’s “New” Macbeth is a Masterpiece without a Master

10. Louis Benezet, 1948: Oxford and the Professors

11. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1948: Rarest Contemporary Description of “Shakespeare” Proves Poet to Have Been a Nobleman

12. EvaTurner Clark, 1948: Alias

13. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1948: Oxford vs. Other “Claimants” of the Edwards Shakespearean Honors, 1593

14. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1948: “In deed as in name: Vere nobilis for he was W… (?)…”

15. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1948: John Lyly as Both Oxford’s and Shakespeare’s “Honest Steward”

Part 2: English Shakespeare Fellowship News-Letters after World War II

1. Preface

2. J.J. Dwyer, 1947: Queen Elizabeth and Her Turk

3. J. J. Dwyer, 1947: The Portraits of Shakespeare

4. Montague Douglas, 1948: Book Review of Shakespeare’s Sonnets and Edward de Vere by Canon Gerald Rendall

5. Percy Allen, 1951: King Lear in Relation to French History

6. H. Cutner, 1951: Provincial Dialect in Shakespeare’s Day

7. Percy Allen, 1952: Book Review of This Star of England by Dorothy and Charlton Ogburn

8. Kathleen Le Riche, 1953: A Portrait of Shake-speare?

9. Gwynneth Bowen, 1954: The Wounded Name

10. T. Adamson, 1955: Shakespeare and Oxford in the Lecture Room

11. J. Shera Atkinson, 1955: The Famous Victories of Henry V

12. John R. Metz, 1955: Gascoigne and De Vere

13. John R. Metz, 1955: The Poet with a Spear

14. Katherine Eggar, 1955: Brooke House, Hackney

15. Editors, 1956: The Aristocratic Look of Shakespeare

16. Rex Clements, 1957: Shakespeare as Mariner

Part 3: Excerpts from Books, 1920s to 1950s

1. Preface

2. B. M. Ward, 1928: The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford

3. Eva Turner Clark, 1937: The Man Who Was Shakespeare

4. Louis P. Benezet, 1937: Shakspere, Shakespeare, and De Vere

5. Alden Brooks, 1937: Factotem and Agent

6. Montague Douglas, 1952: Lord Oxford and the Shakespeare Group

7. Hilda Amphlett, 1955: Who Was Shakespeare? A New Enquiry

8. J. J. Dwyer, 1946: Italian Art in Poems and Plays of Shakespeare

9. Ernesto Grub, 1949: Shakespeare and Italy

10. Louis P. Benezet, 1958: The Six Loves of “Shakespeare”

11. Dorothy and Charlton Ogburn, 1955: The Renaissance Man of England

Part 4: Bonus Selections

1. Preface

2. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1946. Verifying the Secret History of Shake-speares Sonnets

3. Dorothy and Chariton Ogburn, 1959. The True Shakespeare: England’s Great and Complete Man

4. Dorothy and Chariton Ogburn, 1952: This Star of England

VOLUME 5: SO RICHLY SPUN

Four Hundred Years of Deceit are Enough.

Edward de Vere is Shakespeare

Part 1: Shakespearean Authorship Review 1959-1973

1. Preface

2. Julia Cooley Altrocchi, 1959: Ships and Spears in Genoa

3. Ruth Wainewright, 1959: Elizabethan Noblemen and the Literary Profession

4. Gwynneth Bowen, 1959: Debate at the Old Vic – The Shakespeare Mystery

5. Katharine Eggar, 1959: Review of G. Bowen paper: Hamlet, A Mirror of the Time

6. D.F., 1959: Review of Katharine Eggar paper: Lord Oxford and His Servants

7. Julia Cooley Altrocchi, 1959: Edward de Vere and the Commedia dell’Arte

8. Gwynneth Bowen, 1959: Book Review of Louis Benezet’s The Six Loves of Shakespeare

9. Editors, 1959: The Deiphic Oracle

10. Sir John Russell, 1960: Book Review of Joel Hurstfield’s The Queen’s Wards

11. Ruth Wainewright, 1960: Replies to Mr. Mendi’s Criticisms of Who Was Shakespeare?

12. Gwynneth Bowen, 1960: Oxford Did Go to Milan?

13. D.W.T. Vessey, 1961: Freud and the Authorship Question

14. Georges Lambin, 1961: Did Oxford Go North-East of Milan?

15. Gwynneth Bowen, 1961: Editorial Reply Regarding Spinola Letter

16. Gwynneth Bowen, 1961: The Incomparable Pair and “The Works of William Shakespeare”

17. R. Ridgill Trout, 1961: The Clifford Bax Portrait of W. Shakespeare

18. Ruth Wainewright, 1961: Book Review of Martin Holmes’ Shakespeare’s Public

19. Ruth Wainewright, 1961: Review of Prof. Penrose’s Lecture, “The Shakespeare Portraits”

20. Gwynneth Bowen, 1961: Review of Ruth Wainewright’s Lecture, “Macbeth and the Authorship Question”

21. J.H.D., 1961: Obituary of Professor Louis P. Benezet

22. T. Adamson, 1962: Obituary of Chariton Ogburn

23. Editors, 1962: A Backward Look

24. Phyllis Carrington, 1962: Obituary of B. R. Ward [1863-1933]

25. E. Greenwood, 1962: Obituary: George Greenwood [1850-1928]

26. V.A. Demant, 1962: Obituary of J. Thomas Looney [1870-1944]

27. Georges Lambin, 1962: Obituary of Abel Lefranc [1863-1952]

28. Ruth Wainewright, 1962: “Forty Winters”

29. William Kent, 1963: Professor Saintsbury and Shakespeare

30. Ruth Wainewright, 1963: Book Review of Dorothy and Charlton Ogburn, Jr.’s Shakespeare: The Real Man Behind the Name

31. Sir John Russell, 1963: Book Review of Georges Lambin’s Voyages de Shakespeare en France et en Italie

32. Editors, 1963: Review of H. Gibson’s Lecture, “The Case against the Claimants”

33. Editors, 1963: Debate with Orthodoxy, “The Authorship Question”

34. G. Bowen, 1963: Book Review of S. Pitcher’s The Case for Shakespeare’s Authorship of ‘The Famous Victories.’

35. H. Cutner, 1963: Obituary of William Kent

36. Gwynneth Bowen, 1963: Stratfordian Quarter-centenary

37. D.W. Vessey, 1964: Some Early References to Shakespeare

38. Ruth Wainewright, 1964: Review of G. Bowen’s Lecture: “New Evidence for Dating the Plays: Orthodox and Oxfordian”

39. Hilda Amphlett, 1964: Review of Lecture by G. Cimino, “The Golden Age of Padua”

40. Gwynneth Bowen, 1964: Reverberations

41. D.W. Vessey, 1964: After the Pageant: A Meditation for 1965

42. James Walker, 1965: The Pregnant Silence

43. W.A. Ferguson, 1965: The Sonnets of Shakespeare: The “Oxfordian” Solution

44. G. Bowen, 1965: Hackney, Harsnett, and the Devils in King Lear

45. H.W. Patience, 1965: Topical Allusions in King John

46. l.L. McGeoch, 1965: Book Review of A. Falconer’s Shakespeare and the Sea

47. Ruth Wainewright, 1965: Book Review of E. Brewster’s Oxford: Courtier to the Queen

48. Ruth Wainewright, 1965: Review of G. Bowen’s Lecture “The Merchant and the Jew”

49. Gwynneth Bowen, 1965: Review of Ruth Wainwright’s Lecture, “Conflicting Dates for Various Candidates”

50. Gerald Rendall, 1966: A 1930 Toast to Edward de Vere

51. G. Bowen, 1965: Sir Edward Vere and His Mother, Anne Vavasor

52. Frances Carr: Review of Lecture by Marlowe Society Members: “The Death of Kit Marlowe: A Reconstruction”

53. Frances Carr, 1966: Review of Lecture by G. Bowen: “Who Was Kyd’s and Marlowe’s Lord”?

54. Ruth Wainewright, 1966: On the Poems of Edward de Vere

55. Editors, 1966: Brief Note on the “Flower Portrait”

56. W.T. Patience, 1966: Shakespeare and “Authority”

57. Gwynneth Bowen, 1967: Oxford’s Letter to Bedingfield and “Shake-speare’s Sonnets”

58. R. Ridgill Trout, 1967: Edward de Vere to Robert Cecil

59. Editors, 1967: Review of T. Bokenham’s Lecture: “Ben Jonson, Shakespeare and the 1623 Folio”

60. Editors, 1967: Review of D.W. Vessey’s Lecture: “Shakespeare’s Classical Learning”

61. Editors, 1967: Review of Gwynneth Bowen’s Lecture: “The Shakespeare Portraits and the Earl of Oxford”

62. Gwynneth Bowen, 1967: Touching the Affray at the Blackfriers

63. Dorothy Ogburn, 1967: The Authorship of The True Tragedie of Edward the Second

64. Ruth Wainewright, 1967: Book Review of M. Dewar’s Sir Thomas Smith: A Tudor Intellectual in Office

65. Craig Huston, 1968: Edward de Vere

66. Hilda Amphlett, 1968: Titchfield Abbey

67. Ruth Wainewright, 1968: Book Review of Tresham Lever’s The Herberts of Wilton

68. Editors, 1968: Book Review of Christmas Humphreys’ A Cross-Examination of Oxfordians

69. Gwynneth Bowen, 1968: More Brabbles and Frays

70. H.W. Patience, 1968: Earls Come and Castle Hedingham

71. Ruth Wainewright, 1968: Book Review of B. Grebanier’s The Great Shakespeare Forgery

72. Gwynneth Bowen, 1970: What Happened at Hedingham and Earls Come? Part 1

73. Gwynneth Bowen, 1971: What Happened at Hedingham and EarlsColne? Part 2

74. H.W. Patience, 1970: Note on the 16th Earl of Oxford

75. Alexis Dawson, 1970: Master Apis Lapis

76. D.W. Vessey, 1970: Book Review of G. Akrigg’s Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton

77. D.W. Vessey, 1970: Review of Sir John Russell’s Lecture: “For and Against William of Stratford: A Barrister’s Evaluation”

78.Gwynneth Bowen, 1971. Review of Lecture by Ruth Wainewright “All’s Well That Ends Well and the Authorship Question”

79. Ruth Wainewright, 1971: Review of Alexis Dawson’s Lecture “They Tried to Tell Us”

80. Gwynneth Bowen, 1972: Purloined Plumes

81. Minos Miller, 1972: Address to the Shakespearean Authorship Society on its 50th Anniversary

82. Gwynneth Bowen, 1972: Book Review of C. Sisson’s The Boar’s Head Theatre: An Inn-Yard Theatre of the Elizabethan Age

83. Gwynneth Bowen, 1973: Oxford’s and Worcester’s Men and the “Boar’s Head”

84. Francis Edwards, 1973: Oxford and the Duke of Norfolk

Part 2: Bonus Selections

1. Preface

2. Gywnneth Bowen, 1951: Shakespeare’s Farewell

3. William Kent, 1947: Edward de Vere, the Real Shakespeare

4. Charles Wisner Barrell, 1940: Identifying Shakespeare by X-ray and Infrared Photography

5. Ruth Loyd Miller, 1975: The “Ashbourne” Goes To Court

6. Percy Allen, 1934: Anne Cecil, Elizabeth and Oxford

/////////

Quite a lineup, eh? All of us who feel it’s important to investigate the Shakespearean authorship can be proud of this amazingly rich body of research and writing — by extraordinary men and women — that stands as the foundation of more great work done up to, and including, the present.

Published in: Uncategorized

on October 4, 2009 at 12:55 am

Leave a Comment

Tags: altrocchi, authorship, building, case, earl of oxford, edward de vere, looney, mark anderson, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, shake-speare's treason, Shakespeare, shakespeare authorship, shakespeare by another name, Shakespeare's law, sonnet 107, sonnets, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: altrocchi, authorship, building, case, earl of oxford, edward de vere, looney, mark anderson, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, shake-speare's treason, Shakespeare, shakespeare authorship, shakespeare by another name, Shakespeare's law, sonnet 107, sonnets, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“The Plea Bargain for Southampton’s Life” – The Living Record, Chapter 43

One of the big questions about the Shakespeare sonnets is whether they are arranged by the author to create an ongoing chronicle, in the form of a diary of private letters; and the resounding answer of the Monument Theory is … Yes!

A Contemporary Report of the Essex-Southampton trial, showing Edward de Vere as highest-ranking earl on the tribunal

My aim is to demonstrate this answer until, at some point, it becomes self-evident.

The first forty sonnets of the 100-sonnet central sequence are within four chapters of ten sonnets each, covering forty days from the night of the failed Essex Rebellion of February 8, 1601. Oxford is writing to and about Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, who remains in his Tower prison room as a convicted traitor who is expected to die by execution:

THE CRIME – sonnets 27-36 – February 8 – 17, 1601

THE TRIAL – sonnets 37-46 – February 18 – 27, 1601

THE PLEA – sonnets 47-56 – February 28 – March 9, 1601

REPRIEVE – sonnets 57-66 – March 10 – 19, 1601

Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford

CHAPTER THREE – THE PLEA

(Oxford is trying to solidify a “league” or plea bargain with Secretary Robert Cecil on behalf of Southampton, his son by the Queen and her rightful successor by blood. The prince is “locked up” in the Tower while Oxford is desperately putting forth “the lawful reasons” for the Queen to excuse her son and spare his life. [His dealings are actually with Cecil, who needs to bring James of Scotland to the throne upon Elizabeth’s death; otherwise, he will lose all his power and most likely his life.] To that end Oxford visits the Tower and personally tries to persuade Southampton to forfeit any claim as Elizabeth’s natural heir. Oxford’s “grief lies onward” as he rides away from “where thou art” in the prison, while “strange shadows on you tend” — the shadows of disgrace and coming death, during “this sad interim” between the tragedy of the rebellion and whatever the outcome will be.)

Son 47 – Feb 28 – “A League is Took”

Son 48 – Mar 1 – “Locked Up”

Son 49 – Mar 2 – “Lawful Reasons”

Son 50 – Mar 3 – “My Grief Lies Onward”

Son 51 – Mar 4 – “Where Thou Art”

Son 52 – Mar 5 – “Up-Locked”

Son 53 – Mar 6 – “Strange Shadows on You”

Son 54 – Mar 7 – “Sweet Deaths”

Son 55 – Mar 8 – “‘Gainst Death”

Son 56 – Mar 9 – “This Sad Interim”

Tower of London

Has anyone had any other plausible explanation for the torrent of legal terms and “dark” imagery in these sonnets, along with the author’s emotional turmoil and insistence that the beloved younger man is “away” and “locked up”?

The ten sonnets of this chapter are packed with such images and expressions:

“Thy self away … bars [locks, barricades] … my greatest grief … locked up … closure [walls] … to guard the lawful reasons on thy part … the strength of laws … I can allege no cause … tired with my woe … my grief lies onward and my joy behind … excuse … offence … where thou art … excuse … excuse … key … up-locked … imprisoned … millions of strange shadows on you tend … die to themselves … sweet deaths … death and all-oblivious enmity … the ending doom … the judgment … perpetual dullness … this sad interim …”

We’ll take up the story as it proceeds through Sonnets 47-56, with Oxford desperately seeking a [legal] remedy for 27-year-old Southampton before it’s too late. These sonnets reflect the very real suspense that was building and building within 50-year-old Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, as he labored behind the scenes and set down this “living record” of his royal son for “the eyes of all posterity that wear this world out to the ending doom.” [Sonnet 55, lines 11-12]

Published in: Uncategorized

on October 3, 2009 at 2:28 am

Leave a Comment

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, legal terms, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shake-speare's treason, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 107, sonnet 47, sonnet 48, sonnet 49, sonnet 50, sonnet 51, sonnet 52, sonnet 53, sonnet 54, sonnet 55, sonnet 56, sonnets, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, legal terms, monument, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shake-speare's treason, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, shakespeare's treason, sonnet 107, sonnet 47, sonnet 48, sonnet 49, sonnet 50, sonnet 51, sonnet 52, sonnet 53, sonnet 54, sonnet 55, sonnet 56, sonnets, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“And By Their Verdict” – The Living Record – Chapter 41

Excerpts from The Monument for Sonnets 43-44-45-46

Waiting for the execution of Essex and attempting to save Southampton’s life, the Earl of Oxford returns to the theme of the first of the prison verses, Sonnet 27, when his royal son appeared to him as “a jewel hung in ghastly night.” In the daytime, he sees Southampton as “un-respected” (a convicted traitor in disgrace); at night, during sleep, he sees him in dreams as the true royal prince. The “Summer’s Day” of Southampton’s royal blood has turned to darkness, shadow, and night; reality itself has been turned inside out.

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Sonnet 43 – “In Dead Night” – 24 Feb 1601

When I most wink, then do mine eyes best see;

For all the day they view things un-respected,

But when I sleep, in dreams they look on thee,

And darkly bright, are bright in dark directed.

Then thou whose shadow shadows doth make bright,

How would thy shadow’s form form happy show

To the clear day with thy much clearer light,

When to unseeing eyes thy shade shines so?

How would (I say) mine eyes be blessed made

By looking on thee in the living day,

When in dead night thy fair imperfect shade

Through heavy sleep on sightless eyes doth stay?

All days are nights to see till I see thee,

And nights bright days when dreams do show thee me.

The Tower of London

The Execution of Essex – 25 Feb 1601

“The death of Essex left Sir Robert Cecil without a rival in the Court or cabinet, and he soon established himself as the all-powerful ruler of the realm.” – Agnes Strickland, Elizabeth, 1906, p. 675

“The fall of Essex may be said to date the end of the reign of Elizabeth in regard to her activities and glories. After that she was Queen only in name. She listened to her councilors, signed her papers, and tried to retrench in expenditure; but her policy was dependent on the decisions of Sir Robert Cecil.”- Charlotte Stopes, The Life of Henry, Third Earl of Southampton, 1922, p. 243

Sonnet 44 – “Heavy Tears” – 25 Feb 1601