“After the Rebellion” — Hank Whittemore at the Shakespearean Authorship Trust (S.A.T.) conference at Shakespeare’s Globe – November 2019

Published in:

on March 11, 2020 at 6:57 pm

Comments (2)

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, Venus and Adonis, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, confined doom, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, Shakespeare's law, southampton, The Monument, tower of london, Venus and Adonis, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

The Launch of the “Shakespeare” Pen Name (Who Knew What & When?) and Its Aftermath

Following is a talk I gave to the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Conference on 17 October 2019 at the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, CT:

Part One

Samuel Clemens drew upon a wealth of personal experience in his work; and in his later years, he made the remark: “I could never tell a lie that anybody would doubt, nor a truth that anybody would believe.” Imagine old Sam on his porch out there and Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, laughing along with him. And Oxford reminding him what Touchstone said in As You Like It: “The truest poetry is the most feigning” – in other words, pretending — telling truth by allegory and a “second intention.” Both men knew that more truth can be told and believed when dressed as fiction, whether it’s Huckleberry Finn or Hamlet. And, of course, both men wrote under pen names.

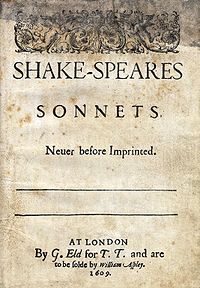

(Dedication of “Venus and Adonis” in 1593 to Southampton with first printing of the Shakespeare name)

I want to talk first about the launch of the pen name “Shakespeare” in 1593, on the dedication of Venus and Adonis to Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, asking, “Who Knew What and When?” – or – “What Did They Know and When Did They Know It?” The question is posed in relation to five individuals.

Queen Elizabeth – Did her Majesty see the letter to her from early reader William Reynolds, saying she was the subject of a crude parody in the character of Venus? Did she know who had written this scandalous, instant bestseller? If she did know, when did she know it?

William Cecil Lord Burghley – Reynolds also wrote to the chief minister, saying he was offended by this portrait of Elizabeth as a “lusty old” queen. Meanwhile, Burghley was Southampton’s legal guardian and still pressuring him to marry his granddaughter, Elizabeth Vere (who may or may not have been the natural daughter of Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford). Therefore anything involving Southampton would be of great interest to Burghley and his rapidly rising son Robert Cecil.

After the death in 1590 of Francis Walsingham, head of the secret service, William and Robert Cecil had taken over the crown’s network of spies and informants. They made it their business to know everything; and now they were gearing up for the inevitable power struggle to control the succession upon Elizabeth’s death.

The queen refused to name her successor, even though she was turning sixty and could die any moment. The Cecils were preparing for the fight with Robert Devereuex, second Earl of Essex, with whom Southampton was closely allied. Could they allow this “Shakespeare” to dedicate to Southampton such a popular, scandalous work and not know the author? What did Burghley know and when did he know it?

Henry Wriothesley Lord Southampton, nineteen, whom we can imagine arriving at the royal court, where folks had their copies of Venus and Adonis with its dedication to him. Might they be curious about “William Shakespeare”? And about his relationship to Southampton? What did the earl know and when did he know it?

John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, who issued the publishing license in his own hand. He had a large staff for that purpose and normally delegated readings of manuscripts and signings-off on licenses, but now he took it upon himself. This strict archbishop was in charge of all government censorship. Why would he give his personal approval of such salacious poetry? Why would he allow this possibly dangerous political allegory into the market? Would he have done so without prior authorization from the queen and Burghley?

Whitgift had been appointed archbishop in 1583 and had gained her Majesty’s full trust and admiration. In 1586 he was given the authority to peruse and license all manuscripts and the power to destroy the press of any printer. He suppressed the Puritans so harshly that in 1588 they began to publish pamphlets against him, led by a writer using the pen name “Martin Marprelate” (who was “marring the prelates”). The archbishop responded with a ruthless campaign of retaliation, using pamphlets turned out by members of Oxford’s writing circle such as Tom Nashe and John Lyly. Apparently, the earl himself wrote against “Marprelate” under the pen name “Pasquil Cavaliero.” (One pen name battling another!)

At the end of the 1590s, the archbishop will issue a decree ordering the burning of a long list of books, among them several based on works of Ovid. The condemned books will be publicly burned in the infamous Bishops’ Bonfire of 1599, but none will include works attributed to “Shakespeare” — not even Venus and Adonis or Lucrece, both based on Ovid. (“Shakespeare” never got into trouble for his writing.) Now in 1593, Whitgift personally authorizes Venus and Adonis for publication by Field.

Richard Field, Publisher-Printer, who entered Venus and Adonis at the Stationer’s Register in April 1593.

Field will print Love’s Martyr in 1601 with The Phoenix and Turtle as by “William Shake-speare” — hyphenated, as if to confirm that it’s a pen name. (Presumably he was the son of Henry Field, a tanner in Stratford-upon-Avon; but modern researchers are finding it difficult to verify that presumption.) Regardless of his background, by age seventeen in 1579 he was in London. He apprenticed for several years under the esteemed printer and French refugee Thomas Vautrollier, who died in 1587. A year later Field married Vautrollier’s widow and, at twenty-six, he took over the publishing business.

He was a dedicated Protestant, committed to the policies of Queen Elizabeth. It’s been said Field was “Burghley’s publisher.” Later he would issue Protestant books in Spanish, for sale in Catholic Spain, under “Ricardo del Campo” – another pen name.

In 1589 Field published The Arte of English Poesie, by a deeply knowledgeable writer choosing not to identify himself. Along with Richard Waugaman and others, I hold the view that The Arte was written (wholly or in part) by Oxford, whose own verse is cited for description and instruction, not to mention that he himself is fulsomely praised as chief poet of the Elizabethan court.

The anonymous author of The Arte addresses his entire tract to Elizabeth – with distinct echoes of Oxford’s own praise of the queen in his elegant Courtier preface of 1572. The invisible author also uses the kind of alliteration Oxford so enjoyed; for example, he tells her Majesty:

“You, Madam, my most Honored and Gracious, if I should seem to offer you this my desire for a discipline and not a delight … By your princely purse, favours and countenance, making in manner what ye list, the poor man rich, the lewd well learned, the coward courageous, and the vile both noble and valiant: then for imitation no less, your person as a most cunning counterfeit lively representing Venus…”

(Here is Richard Field, who will publish Venus and Adonis four years later, issuing an anonymous book in which the author likens Queen Elizabeth to Venus.)

“Venus and Adonis” by Titian, the painting that “Shakespeare” must have seen in Venice (showing Adonis wearing his bonnet)

There is strong evidence that Oxford wrote the first version of Venus and Adonis in the latter 1570s after returning from Italy, where he had made his home base in Venice. For example, the poem contains a lifelike portrait-in-words of Venus trying to seduce young Adonis, who, significantly, is wearing his bonnet. Without question this section of the narrative poem is a vivid description of the painting in Venice at Titian’s own house, which Oxford must have visited (as most traveling nobles did) – because in that house was Titian’s only painting of Venus and Adonis (among his many others of the same subject) in which the young god is wearing his bonnet.

It may also be that Oxford was creating an allegory of his own experience as a young man pursued by Elizabeth. Adonis is killed by the spear of a wild boar — perhaps the same boar of Oxford’s earldom, as though his own identity is officially killed by the spear of “Shakespeare,” his new pen name. From the blood of Adonis, a purple flower springs up, and Venus tells it: “Thou art next of blood and ‘tis thy right.” Then the lustful goddess flies off to Paphus, the city in Cyprus sacred to Venus, to hide from the world. Her silver doves are mounted through the empty skies, pulling her light chariot and “holding their course to Paphus, where their Queen means to immure herself and not be seen.”

Oxford had an extensive personal history of publicly likening Queen Elizabeth to Venus. In Euphues and his England, the novel of 1580 dedicated to the earl, she is portrayed as both the Queen of Love and Beauty and the Queen of Chastity: “Oh, fortunate England that hath such a Queen! … adorned with singular beauty and chastity, excelling in the one Venus, in the other Vesta ….” — the sexual goddess and the virginal goddess, both at once.

In the Paradise of Dainty Devices (1576), the scholar Steven May writes, Oxford definitely likens Elizabeth to Venus: “But who can leave to look on Venus’ face?” the poet asks, referring to “her alone, who yet on th’earth doth reign.”

In the final chapter of Arte, the author apologizes to the queen for this “tedious trifle” and fears she will think of him as “the Philosopher in Plato who failed to occupy his brain in matters of more consequence than poetry,” adding, “But when I consider how everything hath his estimation by opportunity, and that it was but the study of my younger years in which vanity reigned…”

(“When I consider how everything” will be echoed in sonnet 15, which begins, “When I consider everything…”)

The anonymous author tells Elizabeth that “experience” has taught him that “many times idleness is less harmful than profitable occupation.” He refers sarcastically, sounding like Hamlet, to “these great aspiring minds and ambitious heads of the world seriously searching to deal in matters of state” who become “so busy and earnest that they were better be occupied and peradventure altogether idle.”

(Who else would dare to write that description to her Majesty about members of her own government? Oxford had written similar thoughts in his own poetry such as, “Than never am less idle, lo, than when I am alone.” At the same time, he pledges his “service” to her, according to his “loyal and good intent always endeavoring to do your Majesty the best and greatest of those services I can.” Oxford always talks about serving the queen, as he wrote to Burghley, “I serve her Majesty, and I am that I am.”)

Richard Field publishes this work of 1589, written by an anonymous author sounding much like Oxford, and containing some of the earl’s own work, praising him to the skies – and then Field dedicates it to Burghley. “This book,” he tells the most powerful man in England, “coming to my hands with his bare title, without any Author’s name or any other ordinary address, I doubted how well it might become me to make you a present thereof.”

He was surprised and mystified to see this manuscript just flying over the transom into his hands; however, seeing that the book is written to “our Sovereign lady the Queen, for her recreation and service,” Field publishes the work and even dedicates it to Burghley. In his dedication, he also sounds as if Oxford helped him, as when he writes alliteratively of “your Lordship being learned and a lover of learning … and myself a printer always ready and desirous to be at your Honorable commandment.”

Four years later Field publishes Venus and Adonis dedicated to Southampton, whom Burghley, with the queen’s blessing, hopes to gather into his own family. Even orthodox commentators recognize that the high quality of the printing suggests Shakespeare’s direct involvement, as Frank Halliday writes in A Shakespeare Companion: “The two early poems, Venus and Adonis and Lucrece, both carefully printed by Field, are probably the only works the publication of which Shakespeare personally supervised.” (Imagine the Earl of Oxford working side by side with Richard Field at his shop in Blackfriars, to fine-tune the printing!) Now the manuscript goes to Whitgift, chief censor for everything published in England, and he signs off in his own hand – a fact that Field quickly advertises in the Stationers Register.

The question is posed in relation to Publisher Richard Field, Archbishop John Whitgift, Queen Elizabeth, Lord Burghley and the Earl of Southampton: Who knew what and when? What did they know and when did they know it?

My answer is that they all knew about the launch of Oxford’s new pen name and knew it before this work was published. They each knew who “Shakespeare” was and they allowed the earl to publish it and dedicate it to Southampton. The very individuals who were most closely involved, with the most at stake, and could make such decisions, must have worked directly, or indirectly, with each other – and with the author himself – to launch the famous pen name.

Part Two

There is another dimension to the pseudonym that I would like to describe. It begins back in 1583, when Protestant England and Catholic Spain were definitely at war; and gearing up to defend against this mighty enemy was the queen’s great Puritan spymaster, Francis Walsingham, who quickly organized a new company of players. The Puritans generally hated the public theater, but Walsingham knew its value in terms of propaganda.

The new company, approved by Burghley and patronized by Elizabeth, was called the Queen’s Men. It was comprised of two separate troupes touring the country to rouse patriotic fervor and unity. All existing companies – including Oxford’s — contributed their best actors – and de Vere collected his expanding group of writers at a mansion in London (nicknamed Fisher’s Folly) for scribes such as Nashe, Lyly, Watson, Greene, Munday, Churchyard, Lodge and many others.

(Imagine Michelangelo’s studio filled with artists working together under a single guiding hand.)

In the 1580s these writers turned out dozens, even hundreds of history plays. Among them were Oxford’s own early versions of Shakespeare histories, anonymous plays such as The Troublesome Reign of King John, The True Tragedy of Richard Third, The True Chronicle History of King Leir and The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth, the latter containing the entire framework for Henry Fourth Parts One and Two and Henry the Fifth as by Shakespeare.

Their weapons were not swords or guns or ships, but words, giving birth to an inspiring new English language and vision of national identity – a powerful weapon that de Vere was creating and guiding as well as helping to finance. And in 1586 the queen rewarded him with an extraordinary annual allowance of a thousand pounds, paid according to the same formula used to finance Walsingham for his wartime secret service. When the Spanish invasion by Armada arrived in 1588, volunteers from all parts of England responded – Protestants, Puritans, Catholics, speaking different dialects and often needing to be translated, all joining in the face of a common enemy.

Once the Great Enterprise of King Philip had been turned back, however, that same government had no more use for the writers. Having harnessed their talent and work to touch the minds and hearts of the queen’s subjects, the government now became wary of them, perhaps afraid of their freedom of expression and power to influence her Majesty’s subjects.

After defeating the enemy without, the government now focused upon its real or potential enemies within. The end game of internal power struggles was just beginning. Who would gain control of the inevitable succession to Elizabeth? Oxford had been the central sun from which the writers had drawn their light, and around which they had revolved; but now he was deliberately squeezed with old debts and could no longer support them, so they began to fly out of orbit and disappear.

By 1590, the year Walsingham died, Oxford’s secretary and stage manager John Lyly was out of a job; in 1591, Thomas Lodge escaped poverty by sailing to South America; in September 1592, Thomas Watson died and so did Robert Greene (if, in fact, Greene was a real person and not another pen name); on 30 May 1593, Christopher Marlowe was stabbed to death; later that year, Thomas Kyd was tortured on the rack, leading to his death.

Lyly, Lodge, Watson, Greene, Marlowe, Kyd: all gone. They disappeared in a kind of bloodbath, into a metaphorical graveyard of writers; and Oxford himself disappeared. He withdrew from court and vanished from London. He remarried (his first wife, Anne Cecil, had died in 1588) and became something of a recluse at Hackney – undoubtedly revising his previous plays.

As far as the general public knew, Oxford no longer existed; some people even thought he was dead; but in the spring of 1593, just when Marlowe was being murdered, something else was afoot. From below the graveyard of writers, without any paper trail or personal history, the heretofore unknown “William Shakespeare” – a disembodied pen name — suddenly rose in defiance, shaking the spear of his pen and asserting his power in the Latin epigraph from Ovid on the title page of Venus and Adonis, translated as: “Let the mob admire base things! May Golden Apollo serve me full goblets from the Castilian Spring!” Who is this Shakespeare? And which side is he on?

The sudden appearance of this name was not on the title page, but, rather, inside the book, and linked (directly, and uniquely) to nineteen-year-old Southampton. And in the very next year, 1594, the poet made himself even clearer, dedicating Lucrece to Southampton: “The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end … What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours, being all I have, devoted yours.” All that the pen name has is a multitude of written works to be published under that name – the two poems, plus any other writings that will use “Shakespeare” in the future.

A metamorphosis has taken place. In this second dedication, the pen name is speaking for itself and not, in the first place, for the Earl of Oxford, who has disappeared; the pen name is saying to young Lord Southampton: “ALL I HAVE – ANYTHING WRITTEN UNDER THIS NAME — IS NOW AND FOREVER DEVOTED TO YOU. THEY ARE YOURS, TO DO WITH WHAT YOU WILL.” It is all “YOURS … YOURS … YOURS.”

The disembodied pen name has declared itself on the side of the young nobility, in favor of the Essex faction of which Southampton is a prominent member. Soon that young earl firmly and finally rejects Burghley’s marriage plans for him. Essex has been in secret communication with James in Scotland – pledging his support for the King, in return for the promise of James’ help against Burghley and his son Robert Cecil.

So long as Elizabeth remains alive, she can still name her successor; meanwhile, a main goal of Essex and Southampton is to keep the Cecils from assuming even more power after she dies. We are now in the very short period spanning 1595 to 1600 – six years – in which the great issuance of Shakespeare plays occurs: earlier plays that are now revised for the printing press and the public playhouse.

Robert Cecil becomes Principle Secretary in 1596; in the following year, he tries to have all public playhouses shut down and nearly succeeds; in fact, he does succeed in destroying the Swan Playhouse as a venue for plays.

And upon the death of his father, Burghley, in August 1598, Secretary Cecil begins to gain the full trust of Her Majesty and the power to control her mind, emotions and decisions. Now the gloves come off and “Shakespeare” suddenly – for the first time — makes its appearance on printed plays. Over the next three years comes the historic rush of quartos. In 1598 and 1599, four plays are printed with “Shake-speare” hyphenated, emphasizing it’s a pen name: Love’s Labour’s Lost, Richard III, Richard II and 1 Henry IV. The playwright had “newly corrected” two of these plays, quite obviously having written them their first versions much earlier.

Four more plays are published in 1600, all using the pen name without any hyphen: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2 Henry IV, The Merchant of Venice and Much Ado About Nothing. And three others also appear in that time frame, but still anonymous: Romeo and Juliet, 3 Henry VI, and Henry V. Many of these plays – especially the histories – deal with issues of kingship, of what kind of monarch should or should not rule, the right and wrong ways to choose a successor, the consequences of deposing a rightful king. These issues are swirling on and off the stage, in allegory and in real life, all around the aging queen, who refuses to make a choice while she still has the strength to do so.

Edward, Earl of Oxford was summoned as a judge to the 1601 trial of Essex and Southampton — the same Southampton to whom “Shakespeare” had pledged his “love … without end.”

Southampton takes charge of planning an assault on Whitehall Palace, aiming to remove Cecil and confront Elizabeth without interference. If they gain entrance to her presence, they will beg the queen to fulfill her responsibility by choosing a successor.

Members of the Essex faction meet with the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, Shakespeare’s company, paying the actors to give a special performance of Richard II at their own playhouse, the Globe, on Sunday 7 February 1601. Southampton is in charge of the Shakespeare plays and, most likely, he himself pays for the performance – with its deposition scene of King Richard handing over his crown to Bolinbroke, who becomes Henry IV.

(The play is instructional. It’s also a cautionary tale: Richard is murdered in prison by Pierce of Exton, who mistakenly believes he’s carrying out the king’s wishes.)

Cecil uses this performance to summon Essex that night and trigger the chaotic events of the following day. By midnight of the Eighth of February, Essex and Southampton are both arrested and taken by river through Traitors Gate into the Tower, facing charges of high treason and almost certain execution. Of course, this play of royal history is another allegory, and Elizabeth will famously cry out six months later, “I am Richard the Second, know ye not that?”

So long as Southampton is in the prison, there will be no authorized printings of new Shakespeare plays. In effect, the pen name goes silent. The actors of Shakespeare’s company are summoned for questioning, but never the author … but why not? Well, he can’t be summoned, can he? He has no flesh and blood, because “Shakespeare” — after all – is but a pen name.

Postscript

While Southampton languishes in prison, another metamorphosis takes place, as recorded by Oxford in the Sonnets. First, his disappearance: “My name be buried where my body is” (72); and “I, once gone, to all the world must die” (81). Then his sacrifice to the pen name, in a sequence that traditional critics call the Rival Poet series. The true “rival,” however, is not a flesh-and-blood person; rather, it is Oxford’s own pseudonym on the printed page.

Oxford understood that “Shakespeare” would remain attached to Southampton, even as he himself, the true author, faded from the world’s view. The Sonnets would be suppressed upon their publication in 1609, and the quarto would remain underground for more than a century until it reappeared in 1711, like a message in a bottle, carrying Oxford’s true account for posterity. The story — of how Oxford sacrificed himself to save Southampton’s life and gain his freedom — remains within the “monument” of the Sonnets:

“Your monument shall be my gentle verse,/ Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read” (81); “And thou in this shalt find thy monument,/ When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent” (107).

Published in:

on December 2, 2019 at 2:48 pm

Comments (10)

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, s, shakespeare authorship, southampton, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare, William Cecil

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, robert cecil, s, shakespeare authorship, southampton, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare, William Cecil

The Earl of Southampton: Re-posting No. 28 of 100 Reasons Why Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford

One of the most compelling reasons to believe Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford was “Shakespeare” is the central role in the Shakespeare story played by Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton.

The grand entrance of “William Shakespeare” onto the published page took place in 1593, as the printed signature on the dedication to Southampton of Venus and Adonis, a 1200-line poem that the poet called “the first heir of my invention” in his dedication. The second appearance of “William Shakespeare” in print came a year later, with the publication of an 1800-line poem, Lucrece, again dedicated to Southampton.

The Lucrece dedication was an extraordinary declaration of personal commitment to the twenty-year-old earl:

“The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end … What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours … Your Lordship’s in all duty, William Shakespeare.”

“There is no other dedication like this in Elizabethan literature,” Nichol Smith wrote in 1916, and because the great author never dedicated another work to anyone else, he uniquely linked himself to Southampton for all time.

Most scholars agree that the Fair Youth of Shake-speares Sonnets, the sequence of 154 consecutively numbered poems printed in 1609, is also Southampton, even though he is not identified by name. Most further agree that, in the first seventeen sonnets, the poet is urging Southampton to beget a child to continue his bloodline – demanding it in a way that would ordinarily have been highly offensive: “Make thee another self, for love of me.”

“It is certain that the Earl of Southampton and the poet we know as Shakespeare were on intimate terms,” Charlton Ogburn Jr. wrote in 1984, “but Charlotte G. Stopes, Southampton’s pioneer biographer [1922] spent seven years or more combing the records of the Earl and his family without turning up a single indication that the fashionable young lord had ever had any contact with a Shakespeare, and for that reason deemed the great work of her life a failure.”

“Oxford was a nobleman of the same high rank as Southampton and just a generation older,” J. Thomas Looney wrote in 1920, adding that “the peculiar circumstances of the youth to whom the Sonnets were addressed were strikingly analogous to his own.”

- De Vere became the first royal ward of Queen Elizabeth in 1562, under the guardianship of William Cecil (later Lord Burghley), and in 1571 he entered into an arranged marriage with the chief minister’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Anne Cecil.

- Henry Wriothesley became the eighth and last child of state as a boy in 1581-82, also in the chief minister’s custody, and during 1590-91 he resisted intense pressure to enter into an arranged marriage with Cecil’s fifteen-year-old granddaughter, Elizabeth Vere.

The young lady was also Oxford’s daughter, making the elder earl, in fact, the prospective father-in-law. Scholars generally agree that in the seventeen “procreation” sonnets Shakespeare’s tone sounds much like that of a prospective father-in-law or father urging Southampton to accept Burghley’s choice of a wife for him, although the poet never identifies or describes any specific young woman.

J. Dover Wilson writes in 1964: “What man in the whole world, except a father or a potential father-in-law, cares whether any other man gets married?”

Obviously, de Vere and Wriothesley both had an extremely important personal stake in the outcome of this marriage proposal coming from the most powerful man in England, who must have had the full blessing of his sovereign Mistress.

Looney noted that both Oxford and Southampton “had been left orphans and royal wards at an early age, both had been brought up under the same guardian, both had the same kind of literary tastes and interests, and later the young man followed exactly the same course as the elder as a patron of literature and drama.”

The separate entries for Oxford and Southampton in the Dictionary of National Biography, written before the twentieth century, revealed that “in many of its leading features the life of the younger man is a reproduction of the life of the elder,” Looney noted, adding it was “difficult to resist the feeling that Wriothesley had made a hero of De Vere, and had attempted to model his life on that of his predecessor as royal ward.”

A Notice of the Essex-Southampton Trial of Feb. 19, 1600 (1601) with Edward de Vere given prominence as a judge on the tribunal

By the time Southampton came to court at age sixteen or seventeen, Oxford had removed himself from active attendance. It seems that the two shared some kind of hidden story that tied them together:

= As royal wards, both Oxford and Southampton had Queen Elizabeth as their official mother. Even though their respective biological mothers were alive when their fathers died, under English law they became wards of the state, and the queen became their mother in a legal sense.

= Tradition has it that Shakespeare wrote Love’s Labour’s Lost in the early 1590s for Southampton to entertain college friends at his country house; but given the sophisticated wordplay of this court comedy and its intended aristocratic audience, it is difficult to see how Will of Stratford would or could have written it.

= Oxford in the early 1590s was Southampton’s prospective father-in-law.

= After the failed Essex Rebellion in February 1601, Oxford sat as highest-ranking earl on the tribunal for the treason trial of Essex and Southampton.

= The peers had no choice but to render a unanimous guilty verdict; there is evidence that Oxford then worked behind the scenes to save Southampton’s life and gain his eventual liberation, as in Sonnet 35: “Thy adverse party is thy Advocate.”

= On the night of Oxford’s recorded death on 24 June 1604, agents of the Crown arrested Southampton and returned him to the Tower, where he was interrogated all night until his release the following day.

= Henry Wriothesley and Henry de Vere, eighteenth Earl of Oxford (born in February 1593 to Oxford and his second wife, Elizabeth Trentham) became close friends during the reign of James; the earls were known as the “Two Henries.” As members of the House of Lords, they often took sides against the king and were imprisoned for doing so.

On the eve of the failed rebellion led by Essex and Southampton in 1601, some of the conspirators engaged the Lord Chamberlain’s Company to perform Shakespeare’s royal history play Richard II at the Globe; many historians assume, perhaps correctly, that Southampton himself secured permission from “Shakespeare” to use the play with its scene of the deposing of the king. On the other hand, it is possible that Robert Cecil himself arranged for it, so he could then summon Essex to court and trigger the rebellion, which had actually been scheduled for a week later.

Once the rebellion failed and Southampton was imprisoned in the Tower on that night of 8 February 1601, all authorized printings of heretofore unpublished Shakespeare plays abruptly ceased for several years.

After Southampton was released on 10 April 1603, the poet “Shake-speare” wrote Sonnet 107 celebrating his liberation after being “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom,” that is, subjected to a sentence of life imprisonment.

Upon Oxford’s death in virtual obscurity, recorded as occurring on 24 June 1604, a complete text of Hamlet was published.

As part of Christmas and New Year’s celebrations surrounding the wedding of Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery and Oxford’s daughter Susan Vere in December of 1604, the Court of James held a veritable Shakespeare festival. In the days before and after the wedding, seven performances of the Bard’s plays were given. (The royal performances appear to be a memorial tribute to the playwright, rather than a tribute to a living author.) One performance was a revival of Love’s Labour’s Lost, for King James and Queen Anne, hosted by Southampton at his house in London.

After Hamlet in 1604 all publications again ceased, for four years. (King Lear was printed in 1608; Troilus and Cressida was issued in two editions during 1608-09; and Pericles appeared in 1609.) Then the silence resumed, for thirteen more years, until a quarto of Othello appeared in 1622; and finally the First Folio of thirty-six Shakespeare plays was published in 1623. Fully half of these stage works were printed for the first time; the folio included none of the Shakespeare poetry, nor any mention of Southampton or the Sonnets.

The connections between Oxford and Southampton are numerous and significant; the link between the two earls is crucial for the quest to determine the real Shakespeare.

[This post is now Reason 53 of 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford, edited by Alex McNeil with editorial assistance from Brian Bechtold.]

Published in:

on March 21, 2018 at 12:27 pm

Comments (3)

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, southampton, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, henry wriothesley, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, robert cecil, shakesepeare's sonnets, shakespeare authorship, southampton, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Queen Elizabeth as the Dark Lady: “Do I envy those Jacks that nimble leap to kiss the tender inward of thy hand”

“Prominent among these favorites was Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford … He was an agile and energetic dancer, the ideal partner for the queen, and he had a refined ear for music and was a dexterous performer on the virginals.” – Carolly Erickson, “The First Elizabeth” (1983)

How oft, when thou my music music play’st

Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds

With thy sweet fingers when thou gently sway’st

The wiry concord that mine ear confounds,

Do I envy those Jacks that nimble leap

To kiss the tender inward of thy hand…

(Emphasis added)

So begins Sonnet 128, the second verse of the Dark Lady series (127-152); and with Oxford viewed as the author, it is plainly about Elizabeth I, who was fond of playing on her virginals – a musical instrument of the harpsichord family, with “jacks” or wooden shafts that rest on the ends of the keys. The presumption here is that Oxford, an expert musician, composed pieces that he and the queen would play together:

Oxford had been jealous of Sir Walter Raleigh, a “jack” who had leaped into the court’s attention in 1580, when he went to Ireland to help suppress an uprising. He soon became a favorite of the queen, and in 1587 he was knighted and appointed Captain of the Queen’s Guard. Later he helped the government bring Essex to his tragic ending upon the failure of the Essex Rebellion and was said to gloat at the time of the earl’s execution.

“When the news was officially announced that the tragedy was over, there was a dead silence in the Privy Chamber, but the queen continued to play, and the Earl of Oxford, casting a significant glance at Raleigh, observed, as if in reference to the effect of Her Majesty’s fingers on the instrument, which was a sort of open spinet, ‘When Jacks start up, then heads go down.’ Everyone understood the bitter pun contained in this allusion.” – Agnes Strickland, “The Life of Queen Elizabeth” (1910), p. 674, citing “Fragmenta Regalia: Observations on the late Q. Elizabeth, her times and favorites,” Sir Robert Naughton (1641)

[The Monument views the chronological arrangement of the Dark Lady series as beginning with Sonnet 127 on the night of the Rebellion on February 8, 1601; in this context, Sonnet 128 would follow upon the execution of Essex a little more than two weeks later on February 25, 1601. The placement is a perfect fit within that context of the contemporary history.]

The lines about “those Jacks that nimble leap/ To kiss the tender inward of thy hand” recall a letter from Essex to Elizabeth in 1597: “And so wishing Your Majesty to be Mistress of all that you wish most, I humbly kiss your fair hands.”

Francis Bacon apparently recalled the same incident with the virginals (or perhaps one that occurred much earlier) in “Apophthegemes New and Old” (1625): “When Queen Elizabeth had advanced Raleigh, she was one day playing on the virginals, and my Lord of Oxford, & another Noble-man, stood by. It fell out so that the Ledge, before the Jacks, was taken away, so the Jacks were seen [i.e., making them visible]; My Lord of Oxford and the other Noble-man smiled, and a little whispered. The Queen marked it, and would needs know what the matter was? My Lord of Oxford answered that they smiled to see that ‘when Jacks went up, Heads went down.’”

The actual occasion of the incident matters little in terms of its placement in the Dark Lady series or its relationship to Sonnet 128. The point is that there is, in fact, documentary evidence that the Queen and Oxford were together while she played on the virginals and he came up with his now-famous, spontaneous quip about the leaping jacks being like Raleigh, an upstart “jack” at the royal court. To express his bitterness at Raleigh in relation to the execution of Essex, there was no better allusion than this one. [In addition, all recollections of the quip have the same rather obvious allusion to an execution-by-beheading.]

Sonnet 128

How oft, when thou my music music play’st

Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds

With thy sweet fingers when thou gently sway’st

The wiry concord that mine ear confounds,

Do I envy those Jacks that nimble leap

To kiss the tender inward of thy hand…

Whilst my poor lips, which should that harvest reap,

At the wood’s boldness by thee blushing stand.

To be so tickled they would change their state

And situation with those dancing chips,

O’er whom thy fingers walk with gentle gait,

Making dead wood more blest than living lips.

Since saucy Jacks so happy are in this,

Give them thy fingers, me thy lips to kiss.

The list of ways in which Queen Elizabeth permeates the Sonnets of Shakespeare continues to grow:

1 – Sonnet 76: “Ever the Same” – the Queen’s motto in English

2 – Sonnet 25: “The Marigold” – the Queen’s flower

3 – Sonnet 131: “Commanded by the Motion of Thine Eyes” – to a monarch

4 – Sonnet 1: “Beauty’s Rose” – the Queen’s dynasty of the Tudor Rose

5 – Sonnet 107: “the Mortal Moon” – Queen Elizabeth as Diana, the chaste moon goddess

6 – Sonnet 19: “The Phoenix” – the Queen’s emblem

7 – Sonnet 151: “I Rise and Fall” – the courtier as sexual slave to his Queen

8 – Sonnet 128: “Those Jacks that Nimble Leap” – recalling the Queen at her virginals

Published in:

on February 3, 2016 at 1:29 pm

Comments (3)

Tags: authorship, dark lady, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, jacks, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, shakespeare authorship, sonnet 128, virginals, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, dark lady, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, essex rebellion, jacks, monument sonnets, queen elizabeth, queen elizabeth 1, shakespeare authorship, sonnet 128, virginals, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“The Two Most Noble Henries” – Henry de Vere & Henry Wriothesley – No. 89 of 100 Reasons why the 17th Earl of Oxford was “Shakespeare”

“The Portraicture of the right honorable Lords, the two most noble HENRIES revived the Earles of Oxford and Southampton” –

circa 1624

“There were some gallant spirits that aimed at the Public Liberty more than their own interest … among which the principal were Henry, Earl of Oxford, Henry, Earl of Southampton … and divers others, that supported the old English honor and would not let it fall to the ground.” – Arthur Wilson, History of Great Britain (1653), p. 161, referring to the earls’ opposition to the policies of King James in 1621

Venus and Adonis was recorded in the Stationer’s Register on April 18, 1593 and published soon after. No author’s name appeared on the title-page, but the dedication was signed “William Shakespeare” – the first appearance of that name in print.

The epistle was addressed to nineteen-year-old Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, to whom the poet bequeathed Lucrece the following year. Never again would this author dedicate anything to anyone else, thereby uniquely linking Southampton to “Shakespeare” for all time. In fact the poet was so confident of his ability to grant the young earl enduring fame (while paradoxically being certain his own identity would never be known) that he would tell him in Sonnet 81:

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I (once gone) to all the world must die.

On February 24, 1593, less than two months before the registry of Venus and Adonis, a son was born to Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford, forty-three, and his second wife Elizabeth Trentham, about thirty, a former Maid of Honor to Queen Elizabeth. The two had married in 1591 and had moved to the village of Stoke-Newington, just north of Shoreditch and the Curtain and Theater playhouses.

The boy, destined to become the eighteenth Earl of Oxford, was brought to the Parish Church on March 31, 1593 and christened Henry de Vere – not Edward, after his father, nor any of the great first names in the Vere lineage (such as John or Robert) all the way back to 1141, when Aubrey de Vere was created the first Earl of Oxford.

“It is curious that the name ‘Henry’ is unique in the de Vere, Cecil and Trentham families,” B.M. Ward commented in 1928. “There must have been some reason for his being given this name, but if so I have been unable to discover it.”

During this time Henry Wriothesley was being sought by William Cecil Lord Burghley for the hand of Oxford’s eldest daughter, Lady Elizabeth Vere. Oxford had become a royal ward in Burgley’s household in 1562; Southampton had followed in 1581; and now on April 18, 1593, little more than two weeks after the christening of Oxford’s male heir as Henry de Vere, the yet-unknown “Shakespeare” was dedicating “the first heir of my invention” to Henry Wriothesley.

“The metaphor of ‘the first heir’ would seem to echo the recent birth of Oxford’s only son and heir to his earldom,” J. Thomas Looney noted in 1920, “and as ‘Shakespeare’ speaks of Southampton as the ‘godfather’ of ‘the first heir of my invention,’ it would certainly be interesting to know whether Henry Wriothesley was godfather to Oxford’s heir, Henry de Vere.”

In the dedication of Lucrece in 1594, the author made a unique public promise to Southampton, indicating a close and caring relationship with its own past, coupled with an extraordinary vision of future commitment:

“The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end … What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours.”

Given that Henry Wriothesley is the only individual to whom “Shakespeare” is known to have written any letters of any kind, he must be the central contemporary individual within the biography of Shakespeare the poet and dramatist. (This is especially so if Southampton is the younger man or “fair youth” of the Sonnets.) The problem, however, is that scholars have never discovered any trace of a relationship between Southampton and William Shaksper of Stratford-upon-Avon, not even any evidence that they knew each other.

But if the poet was Edward de Vere, dedicating his first published work under the newly invented pen name “Shakespeare” to Henry Wriothesley, then his promise that “what I have to do is yours” demands a look into the future for evidence of continuing linkage.

Among the possible evidence is the performance of Richard II as by “Shakespeare” on the eve of the Essex Rebellion on February 8, 1601 led by Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex along with Southampton. If Oxford was the dramatist, had he given permission to use his play for such a dangerous and possibly treasonous motive? Had he given his approval personally to Southampton, to help him? These are among the many questions for which history has no answers.

Looney pointed to a “spontaneous affinity of Oxford with the younger Earls of Essex and Southampton, all three of whom, having been royal wards under the guardianship of Burghley, were most hostile to the Cecil influence at Court.” By the same token, many scholars have noted evidence in the “Shakespeare” plays that the author was sympathetic to the Essex faction – which makes sense if Oxford and “Shakespeare” were one and the same.

Notice of the trial of Essex and Southampton

1600 old style 1601 new

Oxford as highest ranking peer on tribunal

[Oxford was summoned from retirement to act as the senior of twenty-five noblemen on the tribunal at the joint treason trial of Essex and Southampton on February 19, 1601. The peers had no choice but to render a unanimous guilty verdict and to sentence both earls to death. It was “the veriest travesty of a trial,” Ward comments. Essex was beheaded six days later, but Southampton was spared; and after more than two years in prison, he was quickly released by the newly proclaimed King James. CLICK ON IMAGE FOR LARGER VIEW.]

Oxford is recorded as having died at fifty-four on June 24, 1604. That night agents of the Crown arrived at Southampton’s house in London, confiscating his papers and bringing him (and others who had supported Essex) back to the Tower, where he was interrogated before being released the next day. Whether the two events (Oxford’s death and Southampton’s arrest) were related remains a matter of conjecture.

In January 1605, Southampton hosted a performance of Love’s Labours Lost for Queen Anne. The earl apparently had not forgotten how, in the early 1590s, he and his university friends had enjoyed private performances of the play.

In the latter years of James both Henry Wriothesley and Henry de Vere became increasingly opposed to the King’s favorite George Villiers, first Duke of Buckingham, and the projected Spanish match between the King’s son Prince Charles and Maria Ana of Spain – fearing that Spain would grow even stronger to the point of conquering England and turning it back into a repressive Catholic country.

On March 14, 1621, Henry Wriothesley, forty-eight, got into a sharp altercation with Buckingham in the House of Peers; that June he was confined (in the Dean of Westminster’s house and later in his own seat of Tichfield) on charges of “mischievous intrigues” with members of the Commons; and in July of the same year, Henry de Vere, twenty-eight, spent a few weeks in the Tower for expressing his anger toward the prospective Spanish match. Henry Wriothesley was set free on the first of September.

Then on April 20, 1622, after railing against Buckingham again, Henry de Vere was arrested for the second time and confined in the Tower for twenty months until December 1623 – just when the First Folio of Shakespeare plays became available for purchase.

[Whatever might have been the relationship between the imprisonment of Oxford and the publishing of the Folio is unclear; my own feeling is that the printing may well have been spurred by the prospect of Spanish control and the destruction of the Shakespeare plays, especially the eighteen yet to be printed. The Spanish marriage had collapsed in October 1623; but any opinions about whether the Folio printing was triggered by the prospect of the match, and/or the imprisonment of the eighteenth Earl of Oxford are welcome.]

When Henry de Vere volunteered for military service to the Protestant cause in the Low Countries in June 1624, as the colonel of a regiment of foot soldiers, he put forward a “claim of precedency” over his fellow colonel of another regiment, Henry Wriothesley. Eventually the Council of War struck a bargain between the two, with Oxford entitled to precedency in civil capacities and Southampton, “in respect of his former commands in the wars,” retaining precedence over military matters.

[The colonels of the other two regiments were Robert Devereux, third Earl of Essex, the son of Southampton’s great friend Essex, who was executed for the 1601 rebellion; and Robert Bertie, Lord Willoughby, son of Edward de Vere’s sister Mary Vere and his brother-in-law Peregrine Bertie, Lord Willoughby.]

“There seems to have been no ill will between Southampton and Oxford,” writes A.L. Rowse in his biography Shakespeare’s Southampton. “They were both imbued with conviction and fighting for a cause for which they had long fought politically. It was now a question of carrying their convictions into action, sacrificing their lives.”

Southampton and his elder son James (born in 1605) sailed for Holland in August 1624; in November, the earl’s regiment in its winter quarters at Roosendaal was afflicted by fever. Father and son both caught the contagion; the son died on November 5, 1624; and Southampton, having recovered, began the long sad journey with his son’s body back to England. Five days later, however, Southampton himself died at Bergen-op-Zoom at fifty-one. [A contemporary report was that agents of Buckingham had poisoned him to death.]

King James died on March 25, 1625 and Henry de Vere, eighteenth Earl of Oxford died at The Hague on July 25 that year, after receiving a shot wound on his left arm.

But why, after all, might the “Two Henries” be another reason to conclude that Edward de Vere was the real author of the Shakespeare works? Well, to begin with, in this story there is not a trace of the grain dealer and moneylender from Stratford; he is nowhere to be found. More important, however, is the obviously central role in the authorship story played by Henry Wriothesley, who went on to embody the spirit of the “Shakespeare” and the Elizabethan age – the great spirit of creative energy, of literature and drama, of romance and adventure, of invention and exploration, of curiosity and experimentation, of the Renaissance itself.

And, too, Southampton had become a kind of father figure to the sons of Oxford and Essex and Willoughby – the new generation of those “gallant spirits that aimed at the Public Liberty more than their own interest” and who “supported the old English honor and would not let it fall to the ground.”

How these men must have shared a love for “Shakespeare” and his stirring words! How they must have loved speeches such as the one spoken by the Bastard at the close of King John:

This England never did, nor never shall,

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror

But when it first did help to wound itself.

Now these her princes are come home again,

Come the three corners of the world in arms,

And we shall shock them. Nought shall make us rue

If England to itself do rest but true!

POSTSCRIPT

Oxfordian researcher and author Robert Brazil wrote the following on this topic in his book The True Story of the Shake-speare Publications: Edward de Vere and the Shakespeare Printers:

“In the 1600s Oxford’s son Henry became a very close friend to Henry Wriothesley. They shared a passion for politics, theater, and military adventure. The image of the Two Henries, which dates from 1624 or later, shows the earls of Oxford and Southampton riding horseback together in their co-command of the 6000 English troops in Holland that had joined with the Dutch forces in countering the continued attacks by Spain. The picture serves as a reminder that a close relationship between the Vere family and Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, lasted for decades, and that Southampton CAN be linked historically to the author Shake-speare, provided that said author was really Edward de Vere.”

Published in:

on March 1, 2014 at 11:00 pm

Comments (5)

Tags: Anonymous, authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, Henry de Vere, henry wriothesley, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: Anonymous, authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, Henry de Vere, henry wriothesley, The Monument, tower of london, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

A Paper on the “Rival Poet” of the Sonnets as Oxford’s Pen Name or Persona: “Shakespeare”

Following is the text of a 4,000-word paper on “The Rival Poet” of the Sonnets, which I delivered at the Shakespeare Authorship Studies Conference last week at Concordia University in Portland, Oregon — the point being that the Earl of Oxford’s own rival in relation to Southampton was “Shakespeare,” his own pen name or persona:

I realize the phrase “paradigm shift” is a cliché – but the fact is that we are involved in what Looney in 1920 called a difficult, but necessary, “mental revolution”. Part of it is a rejection of the Stratford conception, but the real fun begins with a compelling replacement. Oxford is such a good fit that we keep finding new evidence in support, and new explanations for things that have been problematic.

The works themselves never change; what does change, through an Oxfordian lens, is our perception of them – and often the picture is turned upside down in quite unexpected ways.With Oxford as the model, it’s as if a light is turned on, and we’re exploring in ways that can’t even occur to someone still looking from the same old angle. It’s as if we’re putting on new eyeglasses that allow us to “see” differently.

So we face the need for many other mental revolutions, spinning off from the main one. And in the process, we still have to shake off some of that old baggage, in the form of deeply ingrained assumptions, based on the old model. But it’s not easy. It’s our nature to hold on to previous assumptions and viewpoints and beliefs as long as possible. Which brings me to my topic – the so-called Rival Poet series of the Sonnets – generally viewed as numbers 78 to 86.

The Stratfordian model forced us to see this series in just one way – namely that other writers or poets, but mainly one particular poet who towers above all the others, is stealing the attentions and affections of the fair youth. When Looney expressed his agreement that the younger man was the Earl of Southampton, he quoted from the rival series itself – from Sonnet 81, about “your name” achieving immortal life – and from what he called the companion sonnet, 82, in which Oxford refers to his own “dedicated words” or public dedications to Southampton.

Stratfordians have postulated many rivals – Barnes, Chapman, Chaucer, Daniel, Davies, Davison, Drayton, Florio, Golding, Greene, Griffin, Harvey, Jonson, Kyd, Lyly, Markham, Marlowe, Martston, Nashe, Peele, Spenser, the Italian Tasso, Watson. Oxfordians have come up with some overlaps, such as Chapman and Marlowe … but adding the likes of Raleigh and the Earl of Essex. The senior Ogburns thought it was both Chapman and Marlowe. Ogburn Jr. took no position. He referred to the rival as “one other poet, whose identity I must leave to the contention of more confident minds.” The late Peter Moore made a well-researched and detailed case for Essex.

Unfortunately, as the Stratfordians have taught us, all the best scholarship in the world is of utterly no help if our basic premises are incorrect.

Using the Stratfordian model, the rival must be some other individual who wrote poetry and who publicly used Southampton’s name:

“Knowing a better spirit doth use your name” – 80

My argument here is that the Oxfordian model opens the way to an entirely new way of looking at the same series – a view of the rival as NONE of those individuals and who is not actually a person but, instead, a persona. In this paper I hope to show that the rival series contains Oxford’s own testimony about the authorship – a grand, poetic, profoundly emotional statement of his dying to the world, and also of his resurrection as a spirit breathing life into the poetical and dramatic luminary known as Shakespeare.

The Stratfordian view gave no reason to look for any kind of authorship statement anywhere, much less in the so-called rival series. The Stratfordian view precluded any authorship question or solution. But Oxfordians contend precisely that Oxford has split himself into two separate entities – on the one hand, he’s Edward de Vere, writing privately in the sonnets; on the other hand, he’s “Shakespeare,” the name on the page and the mythic figure of a Super Poet shaking the spear of his pen.

At the outset we picture Oxford living a double life. We picture the blotting-out or expunging of his true identity and its replacement by a rival identity. We were led to take it for granted that the rival must be some real individual; but from Looney onward we have understood Oxford as having created his own rival – initially in the form of a pen name or pseudonym, which then takes the form of a supposedly real character or player on the world stage.

A good question is: If not for the Stratfordian baggage, would we have postulated a rival in the first place? I think we would have known automatically that Oxford is referring to his alter ego … the other aspect of himself … whom he had named William Shakespeare. It’s “Shakespeare” who signs the dedications to Southampton that continue to appear in new editions. It’s “Shakespeare” who gets all the credit.

But there’s much more to it than that. The clear testimony of the sonnets is that Oxford is fading away … becoming invisible. And that he is making a Christ-like sacrifice to redeem Southampton’s sins or crimes, by taking them upon his own shoulders – offering his own identity as ransom, so the younger man may survive and live for as long as men can breathe or eyes can see.

So shall those blots that do with me remain

Without thy help be borne by me alone. (36)

To guard the lawful reasons on thy part (49)

I (my sovereign) watch the clock for you (57)

In Sonnets 78 to 86 he’s talking about other writers who have dedicated works to Southampton, and praised him, but he means writers in general, whereas he is also and primarily speaking of his own invention or creation, which he inhabits as a spirit. By the end of this series, he will consider himself dead to the world and his ghost, his spirit, now lives within the assumed persona of Shakespeare. He leads up to the sequence by making clear that his coming death to the world revolves around Henry Wriothesley – his need to help and protect him. He’s not dying in a vacuum, but in relation to Southampton:

When I perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse. – 71

After my death, dear love, forget me quite. -72

My name be buried where my body is,

And live no more to shame nor me nor you. – 72

Each line of Oxford’s obliteration is linked to concern for Southampton.

The rival series begins with 78:

As EVERY Alien pen hath got my use,

And under thee their posey doth disperse – 78

“Every Alien Pen” refers to other poets, but it’s mainly E. Ver’s pen name, Shakespeare, which is alien — not his real identity.

But now my gracious numbers are decayed,

And my sick Muse doth give an other place – 79

“I yield to Shakespeare … I step aside and let him take my place, as I decay and disappear.”

O how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame – 80

This is not hyperbole. His fainting is an act of losing consciousness or the ability to speak or write. He also faints by feinting, or deceiving – like the feint of a skilled fencer – by assuming an appearance or making a feint to conceal his real identity. He faints by becoming weaker, feebler … less visible. But in the first line of Sonnet 80 Oxford is crying out to say, directly: “I am the one who is writing to you and using your name. “I am fainting in the process because, while I write of you, I am vanishing into the confines of my creation or invention. I am undergoing a metamorphosis. I am doing this to myself, feeding my spirit to Shakespeare, so the more I write through him, the more I lose my identity … and the faster I die to the world. It is through my own spirit that Shakespeare uses your name, and it’s because of his power – ironically the power I give to him — that I am tongue-tied, silent, and no longer able to write publicly about you.”

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame – 80

And art made tongue-tied by authority – 66

And strength by limping sway disabled – 66

Back in Sonnet 66, his art was made tongue-tied “by authority.” And that’s very specific – he or his art is censored, suppressed; and the force keeping him silent is authority or officialdom, the government. (In King John he writes “Your sovereign greatness and authority,” speaking of the monarch.) So “Shakespeare” the pen name is the agent of authority.

And here the door starts opening to a larger and more important story than merely Oxford disappearing for no reason. The government – in the person of the limping, swaying Robert Cecil – is using Oxford’s own persona of Shakespeare as a weapon against him. Oxford’s own better spirit is making him tongue-tied when it comes to “speaking of your fame” – which again refers to the dedications by Shakespeare, included in every new edition of the narrative poems. “Shakespeare” is the agent of Oxford’s death “to all the world” and “Shakespeare” is also the agent of Southampton’s eternal life.

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth willfully appear – 80

Steven Booth writes that willfully “may have been chosen for its pun on the poet’s name: the saucy bark is full of Will.” I would suggest it’s a pun on the poet’s pen name.

Now in 81 come two famous lines for Oxfordians – because they really sum up the authorship question and provide the answer:

Your name from hence immortal life shall have

Though I (once gone) to all the world must die – 81

Given the argument here, it’s no accident – no coincidence – that these lines of 81 appear in the so-called rival sequence. Southampton’s name from this time forward, from here on, will achieve immortal life, but not necessarily because of these sonnets. (His name never appears directly in the sonnets — although it appears indirectly, such as the constant plays upon his motto ‘One for All, All for One”.) From now on, because of “Shakespeare,” Southampton’s name will achieve immortal life; and also because of “Shakespeare,” my identity will disappear from the world. And it’s in the very next sonnet where we find Oxford referring to his own public dedications to Southampton:

I grant thou wert not married to my Muse,

And therefore mayst without attaint o’erlook

The dedicated words which writers use

Of their fair subject, blessing every book – 82

(The dedications which I write through Shakespeare/ About the fair youth, Southampton, consecrating E.Ver’s books of Venus and Adonis and Lucrece)

Later in this very same sonnet, number 82, is a remarkable pair of lines from Oxford’s private self, as if still insisting upon his own identity before it disappears:

Thou truly fair wert truly sympathized

In true-plain words by thy true-telling friend. – 82

And he’s confirming that the “fair subject” of the dedications is Southampton, whom he now calls “truly fair.” Oxford is “dumb” or silent, unable to speak in public, and as “mute,” which is quite the same, unable to speak.

Which shall be most my glory, being dumb,

For I impair not beauty, being mute – 83

There lives more life in one of your fair eyes

Than both your poets can in praise devise.- 83

(Both Oxford and “Shakespeare”)

Let him but copy what in you is writ,

Not making worse what nature made so clear,

And such a counterpart shall fame his wit,

Making his style admired everywhere – 84

So here we have Oxford giving instructions to his alter-ego: “Hold the mirror up to Southampton’s nature and you will be admired everywhere.”

My tongue-tied Muse…

Then others, for the breath of words respect,

Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect – 85

Here again, he and his Muse are tongue-tied while others can speak out: “Respect me for my silent thoughts and for my actions in your behalf.”

The final verse of the series is Sonnet 86, which by itself tells the story:

Was it the proud full sail of his great verse,

Bound for the prize of (all too precious) you,

That did my ripe thoughts in my brain inhearse,

Making their tomb the womb wherein they grew?- 86

There is only one super poet who can force Oxford’s thoughts into a tomb in his brain, which is also the tomb of these sonnets – as in 17, “Heaven knows it is but as a tomb which hides your life and shows not half your parts” – and the womb of these sonnets wherein Southampton can grow – as in 115, “To give full life to that which still doth grow.”

Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write

Above a mortal pitch, that struck me dead?

No, neither he, nor his compeers by night

Giving him aid, my verse astonished. – 86

It is Oxford’s own spirit, or spirits, teaching his public persona to write with the power of Shakespeare. No other writer, past or present, has struck Oxford dead – but there it is, this is the last sonnet of the sequence. Oxford – in terms of his identity – has been killed.

He, nor that affable familiar ghost

Which nightly gulls him with intelligence,

As victors of my silence cannot boast;

I was not sick of any fear from thence. – 86

The affable familiar ghost – as opposed to an alien ghost – is once again Oxford’s own spirit, which nightly or secretly crams Shakespeare with his substance … or literally with intelligence, that is, secret information that Oxford is inserting within the lines of his plays. To “gull” is to cram full, but also to play a trick on … and of course “Shakespeare” the pen name or persona is totally dependent upon Oxford and therefore unaware of what mischief his spirit is up to.

But when your countenance filled up his line,

Then lacked I matter, that enfeebled mine.

And this final couplet is another direct statement of the authorship problem – As Shakespeare rises in connection with Southampton, so Oxford fades away – as Touchstone in As You Like It tells William the country fellow: “Drink, being poured out of a cup into a glass, by filling the one doth empty the other.”

The so-called rival series is the equivalent of a “movement” of a musical composition, a symphony. It’s a separate piece within a larger structure. Its message can be expressed in a line or two, but Oxford wants a string or sequence of lines. The sequence is one long continuous wail of eloquent mourning. But in fact the actual mourning begins much earlier, with many of the preceding sonnets, which are preoccupied with dying.

Death is necessary if there is going to be a Resurrection. So there is a religious, spiritual aspect, mirroring the sacrifice of Christ. In fact it goes all the way back to Sonnet 27 where Southampton is “a jewel hung in ghastly night” – the image of a man in prison awaiting execution or, if you will, of a man hanging from the cross. In Christian terms there is a father and a son who are separate individuals and yet they are also inseparable. He writes in number 27: “For thee, and for myself, no quiet find.” And in 42: “My friend and I are one.”

There is a long, long preparation for the so-called rival series – These are genuinely religious … spiritual …. And devastating … This is heavy, profound, sorrowful and deeply emotional – what we might expect from a man sacrificing his identity.

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee (27)

Clouds do blot the heaven (28)

Look upon myself and curse my fate (29)

Precious friends hid in death’s dateless night (30)

How many a holy and obsequious tear

Hath dear religious love stolen from mine eye …

Thou art the grave where buried love doth live (31)

When that churl death my bones with dust shall cover (32)

Anon permit the basest clouds to ride

With ugly rack on his celestial face … (33)

Though thou repent, yet I have still the loss;

The offender’s sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offence’s cross (34)

So shall those blots that do with me remain

Without thy help, by me be borne alone (36)

Lay on me this cross (42)

To guard the lawful reasons on thy part (49)

‘Gainst death and all oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth …

So till the judgment that yourself arise (55)

I (my sovereign) watch the clock for you (57)

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned,

Crooked eclipses ‘gainst his glory fight (60)

To play the watchman ever for thy sake (61)

O fearful meditation! (65)

For restful death I cry … (66)

In him those holy antique hours are seen (68)

All tongues, the voice of souls, give thee that due (69)

No longer mourn for me when I am dead (71)

In me thou seest the twilight of such day,

As after Sun-set fadeth in the West (73)

When that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away (74)

Why is my verse so barren of new pride (76)

And here, finally, his verse is like a barren womb, empty of child.

And now we have Sonnet 77, which has been seen as a dedicatory verse – with Oxford speaking at first of “this book” and then, to Southampton at the end, calling it “thy book.”

This is the real opening of the so-called rival series – ten consecutive sonnets from 77 to 86:

And of this book this learning mayst thou taste…

These offices, so oft as thou wilt look,

Shall profit thee, and much enrich thy book. (77)

Yet be most proud of that which I compile,

Whose influence is thine, and born of thee (78)

And in 78, even while “every alien pen hath got my use,” he nonetheless tells Southampton to be “most proud” of these sonnets which he is compiling – or arranging, and he identifies them as having been influenced or inspired by Southampton, and “born” of him, thereby identifying Henry Wriothesley as the “only begetter” of the sonnets, Mr. W.H., the commoner in prison, referred to in the dedication.

Meanwhile the nautical imagery began earlier, for example:

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage on the kingdom of the shore …

When I have seen such interchange of state

Or state itself confounded to decay… (64)

“’Ocean’ or ‘sea’ as a figure for ‘king’ is often found in Shakespeare and his fellow-writers.” (Leslie Hotson)

The hungry Ocean indicates the royal blood of King James advancing upon England, the kingdom of the shore, and the coming of the inevitable interchange of state or royal succession.

But since your worth (wide as the Ocean is)

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear… (80)

The nautical imagery is based now on Southampton’s worth as wide as the Ocean, referring to his royal worth. Southampton’s ocean of blood, his kingly identity, holds up all boats.

I came to this view of the so-called rival by a long indirect route — hypothesizing that the fair youth sonnets ARE in chronological order, and that they lead up to, and away from, Sonnet 107, when Southampton is released from the Tower in April 1603 after being “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom.” That’s a very serious sonnet. It has to do not only with Southampton but with the death of Elizabeth, the succession of James and the end of the Tudor dynasty. If the other sonnets have no relationship to that political subject matter, then Sonnet 107 is one huge anomaly.

A simple question became obvious: Given that Shakespeare is a master storyteller, and given that the high point of this story is Southampton getting OUT of the Tower, it stands to reason that he must have marked the time when Southampton went IN to the Tower back in February of 1601. Otherwise there’s no story at all, no suspense, and his liberation from prison comes out of the blue, apropos of nothing. I came to Sonnet 27 as marking that time with Southampton in the Tower expecting execution and pictured as a Jewel hung in ghastly night. I tracked sonnets reflecting those crucial days after the failed Essex rebellion until the moment of Southampton’s reprieve from execution in March 1601. And in that context it appears that Oxford had made a “deal” involving a complete severance of the relationship between himself and Southampton:

I may not evermore acknowledge thee (36)

This is a crucial part of the story of Oxford sacrificing himself for Southampton, his dying to the world and his undergoing a resurrection as Shakespeare

In Sonnet 84 of the rival series, Oxford refers to Southampton being in confinement and immured within the walls of the prison:

“That you alone are you, in whose confine immured is the store” (84)

The idea of having or lacking PRIDE is important. So at the very end of the previous 10-sonnet sequence, number 76, his private verse was “barren” of such pride:

“Why is my verse so barren of new pride?” (76)

By the end of the rival series, with Sonnet 86, “Shakespeare” has inherited that pride – with the “proud full sail of his great verse” riding on that great ocean of Southampton’s identity as a king.

“Was it the proud full sail of his great verse?” (86)

Oxford’s own private verse is like a barren womb, but now Shakespeare’s public verse is fully pregnant. The end of one chapter was a death; the end of the rival chapter is new life. And Shakespeare is full-bellied riding on the sea of Southampton’s tide of kingship:

“Why is my verse so barren of new pride?” – 76

“Was it the proud full sail of his great verse” – 86

“The sails conceive, and grow big-bellied with the wanton wind” (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

The Prince (now King): “The tide of blood in me … shall mingle with the state of floods and flow henceforth in formal majesty” (2 Henry IV)

And after the rival series ends with Sonnet 86, the very first word of Sonnet 87 is “farewell”:

Farwell, thou art too dear for my possessing …

My bonds in thee are all determinate (87)

Our connection to each other is hereby severed. The deal is done.

Adopting the pen name in 1593 had been Oxford’s means of supporting Southampton through his creation of Shakespeare; but now in 1601, to save Southampton’s life and gain his eventual freedom, he agreed to make it permanent. From now on, even after his death, the rest is silence.

The enormity of Oxford’s sacrifice – completely severing his relationship with Southampton, losing his identity as the great writer – the dashing of his hopes involving succession to Elizabeth and the future of England – his death to the world and resurrection as Shakespeare to save Southampton and redeem his sins and ensure his life in posterity – the enormity of this sacrifice demands a use of words that, in most any other scenario, would seem to be sheer hyperbole, nothing more than “a poet’s rage and stretched meter of an antique song.”

“My gracious numbers are decayed … my sick muse … O how I faint …. Being wracked, I am a worthless boat … the earth can yield me but a common grave … most my glory, being dumb … being mute … my tongue-tied muse … my dumb thoughts.”

This is, in fact, a poet’s rage – but my argument here is that, when it’s viewed within the right context, as part of the correctly perceived picture, the rage is no longer fatuous or “over the top”; instead, it’s honest and real and so, too, are the words expressing it.

For the rival poet series, it’s time for a mental revolution.

—

Published in:

on April 18, 2013 at 11:02 am

Comments (12)

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, rival poet, shakespeare authorship, shakespeare's sonnets, southampton, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

Tags: authorship, Earl of Essex, earl of oxford, edward de vere, henry wriothesley, rival poet, shakespeare authorship, shakespeare's sonnets, southampton, The Monument, whittemore, who wrote shakespeare

“Last Will. & Testament” to be Launched in the United Kingdom

First Folio Pictures has announced that the Shakespeare authorship documentary Last Will. & Testament is scheduled to air in the United Kingdom on Saturday 21 April 2012 at 8:00pm on Sky Arts 2 HD. Congratulations, folks! Special hoorays for producer-directors Lisa Wilson and Laura Wilson Matthias … and Aaron Boyd!

Here’s some of the promotional copy:

Was Will Shakspere, the grain dealer from Stratford, really the literary icon we celebrate today?

The traditional story of a Stratford merchant writing for the London stage has held sway for centuries, but questions over the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays and poems have persisted.

Why is there no definitive evidence of authorship that dates from his lifetime? And why are there discrepancies between the alleged author’s life and the content of his work?