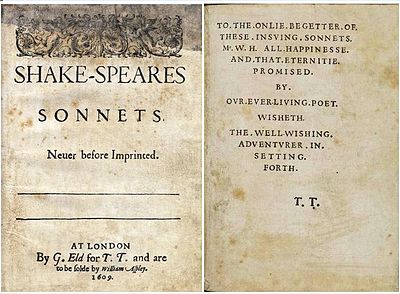

Edward de Vere was in the best position of anyone in England to be the author of the sequence of 154 consecutively numbered sonnets published in 1609 as Shake-speares Sonnets. The known facts about Oxford’s childhood, upbringing, education, and family all interconnect with the sonnets’ language and imagery.

Oxford was nephew to Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1517-1547), who, with Sir Thomas Wyatt, wrote the first English sonnets in the form to be used later by Shakespeare. Oxford himself wrote an early sonnet in that form; entitled Love Thy Choice, it expressed his devotion to Queen Elizabeth with the same themes of “constancy” and “truth” that “Shakespeare” would express in the same words:

“In constant truth to bide so firm and sure” – Oxford’s sonnet to Queen Elizabeth

“Oaths of thy love, thy truth, thy constancy” – Sonnet 152 to the “Dark Lady”

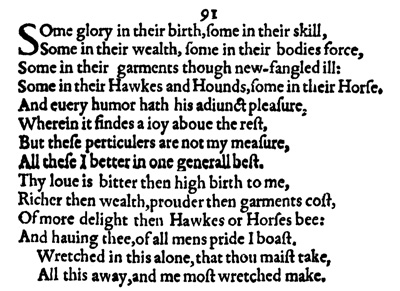

The Shakespeare sonnets are plainly autobiographical, the author using the personal pronoun “I” to refer to himself, telling his own story in his own voice; so it’s only natural that he expresses himself with references to the life he experienced since childhood. Much of that experience is captured in Sonnet 91:

Some glory in their birth, some in their skill,

Some in their wealth, some in their body’s force,

Some in their garments, though new-fangled ill,

Some in their Hawks and Hounds, some in their Horse…

Oxford was born into England’s highest-ranking earldom, inheriting vast wealth in the form of many estates. He was a skilled horseman and champion of two great jousting tournaments at the Whitehall tiltyard. He was the “Italianate Englishman” who wore new-fangled clothing from the Continent. An expert falconer, he wrote poetry comparing women to hawks “that fly from man to man.”

And every humor hath his adjunct pleasure,

Wherein it finds a joy above the rest,

But these particulars are not my measure,

All these I better in one general best.

Thy love is better than high birth to me …

Only someone who already had high birth, and was willing to give it up, could make such a declaration to another nobleman of high birth and make it meaningful; if written to the Earl of Southampton by a man who was not high-born, the statement would be an insulting joke.

Richer than wealth, prouder than garments’ cost,

Of more delight than Hawks or Hounds be,

And having thee, of all men’s pride I boast.

Wretched in this alone, that thou mayst take

All this away, and me most wretched make.

Oxford also left his footprints throughout:

(2) “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow” – He was forty in 1590, when most commentators feel the opening sonnets were written.

(8) “Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly … Mark how one string, sweet husband to another” – He was an accomplished musician, writing for the lute, and patronized the composer John Farmer, who dedicated two songbooks to him, praising his musical knowledge and skill.

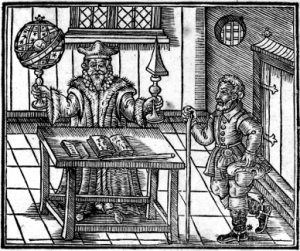

(14) “And yet methinks I have astronomy” – He was well acquainted with the “astronomy,” or astrology, of Dr. John Dee and was praised for his knowledge of the subject.

(23) “As an imperfect actor on the stage” – He patronized two acting companies, performed in “enterludes” at court and was well known for his “comedies” or stage plays.

(33) “Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy” – He studied with Dee, who experimented with alchemy, and both men invested in the Frobisher voyages.

(49) “To guard the lawful reasons on thy part” – He studied law at Gray’s Inn and served as a judge at the treason trials of Norfolk and Mary Stuart and later at the treason trial of Essex and Southampton; his personal letters are filled with intimate knowledge of the law.

(59) “O that record could with a backward look,/ Even of five hundred courses of the Sunne” – His earldom extended back 500 years to the time of William the Conqueror.

(72) “My name be buried where my body is” – In his early poetry he wrote, “The only loss of my good name is of these griefs the ground.”

(89) “Speak of my lameness, and I straight will halt” – He was lamed by a sword during a street fight in 1582.

(96) “As on the finger of a a throned Queen, / The basest Jewel will be well esteemed” – He gave the Queen “a fair jewel of gold” with diamonds in 1580.

(98) “Of different flowers in odor and in hue” – He was raised amid the great gardens of William Cecil, who imported flowers never seen in England, something that accounts for Shakespeare’s vast knowledge of plants.

(107) “And thou in this shalt find thy monument” – He wrote to Thomas Bedingfield in 1573 that “I shall erect you such a monument…”

(109) “Myself bring water for my stain” – He was “water-bearer to the monarch” at the coronation of James on 25 July 1603, in his capacity as Lord Great Chamberlain.

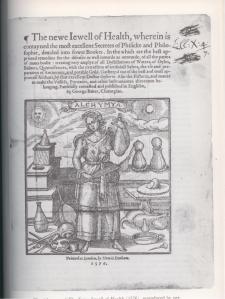

Title page of The New Jewell of Health (1576) by Dr. George Baker, dedicated to Oxford’s wife Anne Cecil, Countess of Oxford

(111) “Potions of Eisel ‘gainst my strong infection” – His surgeon was Dr. George Baker, who dedicated three books to the earl or his wife.

(114) “And to his palate doth prepare the cup” – His ceremonial role as Lord Great Chamberlain included bringing the “tasting cup” to the monarch.

(116) “O no, it is an ever-fixed mark/ That looks on tempests and his never shaken … If this be error and upon me proved,/ I never writ nor no man ever loved” – He wrote: “Who was the first that gave the wound whose fear I wear for ever? Vere.” (Emphasis added)

(121) “No, I am that I am…” – He wrote to Burghley using the same words in the same tone (the words of God to Moses in the Bible) to protest his spying on him.

(125) “Were’t aught to me I bore the canopy” – He was reported to have been one of the six nobles bearing a “golden canopy” over the queen in the procession on 24 November 1588 celebrating England’s recent victory over the Spanish Armada. (But Sonnet 125, I believe, refers to the canopy held over Elizabeth’s effigy and coffin in the funeral procession on 28 April 1603.)

(128) “Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds”– He was an intimate favorite of the queen, who frequently played music on the virginals.

(153) “I sick withal the help of bath desired” – He accompanied Elizabeth and her court during her three-day visit in August 1574 to the City of Bath, the only royal visit to that city; and “Shakespeare” is said to write about this visit in the so-called Bath Sonnets 153-154.

The Sonnets of Shakespeare amount to the autobiographical diary of de Vere. The allusions to his life as a high-born nobleman and courtier, appearing throughout the sequence, come forth naturally and spontaneously. In effect, he left his signature for all to see.

[This post, with significant help from editor Alex McNeil, is now Reason 52 in 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford.]