“It is almost certain that William Shakespeare modeled the character of Prospero in The Tempest on the career of John Dee, the Elizabethan magus.” – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

“Queen Elizabeth’s philosopher, the white magician Doctor Dee, is defended in Prospero, the good and learned conjurer, who had managed to transport his valuable library to the island.” – Frances Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age

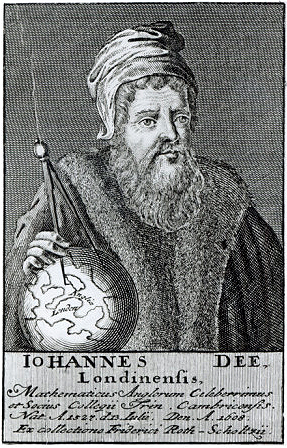

The mathematician and astrologer Dr. John Dee was enlisted by Elizabeth Tudor to name a day and time for her coronation when the stars would be favorable (15 January 1558/59 was the selected date), after which he became a scientific and medical adviser to the queen. A natural philosopher and student of the occult, his name is also associated with astronomy, alchemy and other forms of “secret” experimentation. He became a celebrated leader of the Elizabethan renaissance, helping to expand the boundaries of knowledge on all fronts. With degrees from Cambridge and studies under the top cartographers in Europe, Dee led the navigational planning for several English voyages of exploration.

Defending against charges of witchcraft and sorcery, he listed many who had helped him, citing in particular “the honorable the Earl of Oxford, his favorable letters, anno 1570,” when twenty-year-old de Vere Lord Oxford was about to become the highest-ranking earl at the court of Elizabeth, who would quickly elevate him to the status of royal favorite.

“We may conjecture that it was in 1570 that Oxford studied astrology under Dr. Dee,” B.M. Ward writes. “We shall meet these two [Dee and Oxford] again later, working together as ‘adventurers’ or speculators in Martin Frobisher’s attempts to find a North-West Passage to China and the East Indies.”

Oxford’s links to Dr. Dee, along with his deep interest in all aspects of the astrologer’s work, are yet another piece of evidence pointing to his authorship of the works attributed to William Shakespeare.

In 1584 a Frenchman and member of Oxford’s household, John Soowthern, dedicated to the earl a pamphlet of poems entitled Pandora. His tribute asserted that Oxford’s knowledge of the “seven turning flames of the sky” (the sun, moon and the visible planets, through astrology) was unrivaled; that his reading of “the antique” (a noun referring to classical and ancient history) was unsurpassed; that he had “greater knowledge” of “the tongues” (languages) than anyone; and that his understanding of “sounds” that helped lead students to the love of music was “sooner” (quicker) than anyone else’s:

For who marketh better than he

The seven turning flames of the sky?

Or hath read more of the antique;

Hath greater knowledge of the tongues?

Or understandeth sooner the sounds

Of the learner to love music?

This might as well be a description of the man who wrote The Tempest! It’s a description of an extraordinarily knowledgeable man, which fits “Shakespeare” perfectly; it’s no coincidence that scholars have not only seen Prospero as based on Dee, but, also, viewed Prospero as the dramatist’s self-portrait. Once that window opens, however, the evidence leads to Prospero and “Shakespeare” in the person of Edward de Vere.

Oxford’s familiarity with “planetary influences” is “probably attributable to acquaintance with Dee,” writes Ogburn Jr., “as is likewise the knowledge of astronomy claimed by the poet of The Sonnets.” In regard to the latter, here are some examples of the poet’s easy, personal identification with both astronomy and alchemy:

Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck,

And yet methinks I have Astronomy – Sonnet 14

Or whether shall I say mine eye saith true,

And that your love taught it this Alchemy? – Sonnet 114

Dr. Dee got into trouble when his delving into the supernatural led to necromancy, the magic or “black art” practiced by witches or sorcerers who allegedly communicated with the dead by conjuring their spirits. Stratfordian scholar Alan Nelson, in his deliberately negative biography of Oxford, Monstrous Adversary, includes an entire chapter titled “Necromancer” detailing charges by the earl’s enemies that he had engaged in various conjurations, such as that he had “copulation with a female spirit in Sir George Howard’s house at Greenwich.”

The irony of Nelson’s charge is that it not only serves to portray Oxford as similar to both John Dee and Prospero, but aligns him with the authors of what Nelson himself calls “a long string of necromantic stage-plays” starting in the 1570s. One such play was John a Kent by Anthony Munday, who was Oxford’s servant; another was Friar Bacon and Friar Bungary by Robert Greene, who dedicated Greene’s Card of Fancy in 1584 to Oxford, calling him “a worthy favorer and fosterer of learning” who had “forced many through your excellent virtue to offer the first fruits of their study at the shrine of your Lordship’s courtesy.”

In 1577 both Oxford and Dr. Dee became “adventurers” or financiers of Martin Frobisher’s third expedition to find a sea route along the northern coast of America to Cathay (China) – the fabled Northwest Passage. In fact Oxford was the largest single investor, sinking three thousand pounds, only to lose it all, which may explain Prince Hamlet’s metaphor: “I am but mad north-north-west: when the wind is southerly I know a hawk from a handsaw,” i.e., he’s mad only on certain occasions, the way he was when he invested so much in that expedition to the Northwest.

A play before the queen by the Paul’s Boys on 9 December 1577 appears to have been a version of Pericles, Prince of Tyre, in which the character of Lord Cerimon seems to be a blend of Oxford (one who prefers honor and wisdom to his noble rank and wealth) and Dee (whose “secret arts” included alleged knowledge of properties within metals and stones):

‘Tis known I ever

Have studied physic, through which secret art

By turning o’er authorities, I have,

Together with my practice, made familiar

To me and to my aid the blest infusions

That dwells in vegetives, in metals, stones…(3.2)

Through an Oxfordian lens, The Tempest probably originated in the bleak period between Christmas 1580 and June 1583, when the queen had banished Oxford from court, in effect exiling him (unfairly, just as Prospero, rightful Duke of Milan, suffers in the play). But Oxford would have revised and added scenes over the next two decades, especially near the end of his life in 1604, when the greatest writer of the English language makes his final exit through Prospero — begging us to forgive him for his faults, to pray for him and to set him free from the prison of his coming oblivion:

Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have’s mine own…

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands:

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardon’d be,

Let your indulgence set me free. (Epilogue)

Note: This updated version appears as No. 81 (“The Tempest”) in 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford, edited by Alex McNeil with other editorial assistance by Brian Bechtold.