Waiting for the arrival of my copy of the new Edmondson-Wells book about Shakespeare’s sonnets, I already know what to expect.

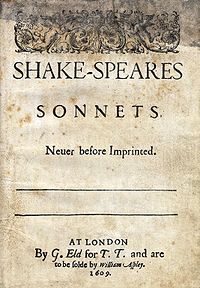

All the Sonnets of Shakespeare will further spread the falsity that SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS, the one hundred and fifty-four consecutively numbered sonnets printed in 1609, can be manipulated at will. It will present the carefully constructed sequence as an ever-expanding dreamscape of Stratfordian faith, much like the mythological Hydra that grows two heads for each one lost.

Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson will also offer the mistaken notion that the Sonnets are only love poems, even though the heart of the sequence contains dozens of references to law, politics, government, state power, trials, prison, crime, revolt and death.

The Shakespearean sonnets may be filled with romantic and sexually erotic words or phrases, but those other, far more important terms are also right there on the printed page; for example: “Sessions, summon, ransom, fault, trespass, adverse party, advocate, liberty, offenders, defendant, plea deny, verdict, locked up, lawful reasons, guard, allege, bloody, offense, up-locked, imprisoned, absence of your liberty, pardon, crime, gates of steel, suspect, fell arrest, bail, dead, knife, attaint, confine, releasing, misprision, judgment, attainted, defense, purposed overthrow, term of life, revolt…”

Those words, too, are on the surface, but our gentlemen scholars of unbounded fancy must view them as “metaphors” when, in fact, they can be related to recorded events from the Essex Rebellion of 1601 to the end of the Tudor Dynasty in 1603. The hundred sonnets between nos. 27 and 126 can be placed as stencils over the lives of Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford, Henry Wriothesley Earl of Southampton and Queen Elizabeth of England during that period, resulting in a true story or “living record” of the younger earl preserved for posterity:

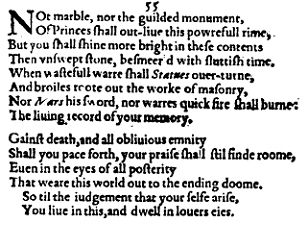

When wasteful war shall Statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword nor war’s quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory. (55, 5-8)

Here are two samples of what appears to be sexually charged writing in the sonnets that can be looked at from more than one perspective:

(1) Sonnets 151 and 152 to the Dark Lady

During a recent interview with Wells, preserved on You Tube, the former president of the Birthplace Trust mentions lines of Sonnet 151:

For thou betraying me, I do betray

My nobler parts to my gross body’s treason;

My soul doth tell my body that he may

Triumph in love; flesh stays no farther reason,

But rising at thy name doth point out thee,

As his triumphant prize; proud of this pride,

He is contented thy poor drudge to be,

To stand in thy affairs, fall by thy side.

No want of conscience hold it that I call

Her love, for whose dear love I rise and fall.

Without any subtext, these lines are graphically sexual. They occur near the end of the Dark Lady series, which Wells and Edmondson have tossed to the wayside; nonetheless, those two gentlemen are correct to see them as filled with blatant sexual imagery. For example, the word “pride” – indicating the author’s penis, rising and falling before the beloved, who has betrayed him. Oxfordians can agree with this obvious expression of “triumph” and betrayal in the myriad ways of love and physical attraction. Given such happy harmony between Stratfordians and Oxfordians, the authorship question is almost forgotten.

In this case, however, if an Elizabethan courtier is writing the above couplet, he cannot help but also think of lines written by Edmund Spenser in Mother Hubbard’s Tale:

Save that which common is, and known to all,

That Courtiers as the tide do rise and fall. (614)

Courtiers of Elizabeth undoubtedly joked that way about themselves. Seeking the patronage of their Sovereign Mistress, that radiant, sexually flirtatious female monarch, they approached her as [literally] servants rising and falling in supplication. They must have joked ruefully about their virtual helplessness as they waited upon her absolute royal power to raise or lower them with a flick of her long, slender finger.

Such was also the case with Edward de Vere in relation to his Queen in Sonnet 151, and, too, as he concludes the Dark Lady series in Sonnet 152, telling her:

And all my honest faith in thee is lost.

For I have sworn deep oaths of thy deep kindness,

Oaths of thy love, thy truth, thy constancy,

And to enlighten thee gave eyes to blindness,

Or made them swear against the thing they see.

For I have sworn thee fair: more perjured eye,

To swear against the truth so foul a lie. (152, 7-14)

I look forward to seeing how Wells and Edmondson deal with those lines in terms of the Stratfordian imagination, but it seems clear the Poet (Oxford) is expressing a deeply heartbreaking and bitter loss of “faith” in this woman for whom he has sworn falsely, perjuring himself and betraying his own knowledge of the “truth” by lying for her.

This is a far cry from the spirited, idealistic young courtier, writing as “Earle of Oxenforde” in his early “Shakespearean” sonnet about the Queen, asking himself:

Above the rest in Court who gave thee grace?

Who made thee strive in honor to be best?

In constant truth to bide so firm and sure,

To scorn the world regarding but thy friends?

With patient mind each passion to endure,

In one desire to settle to the end?

Elizabeth was the one who made him “strive in honor to be best.” She was the only woman “above the rest in Court” who could have compelled him to serve her with “constant truth,” regardless of the consequences. In the early 1570s, when that sonnet was written, did Oxford have a sexual relationship with the Queen? If so, was he still suffering the consequences as expressed decades later in Sonnet 152?

(2) Sonnet 52 to the Fair Youth

This verse to the Earl of Southampton can be viewed entirely in terms of its possible sexual imagery, leading up to “pride” again, for penis, followed by the image of him being “had” by the Poet (with some words emphasized, for reasons to become clear):

So am I as the rich, whose blessed key

Can bring him to his sweet up-locked treasure,

The which he will not every hour survey,

For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure.

Therefore are feasts so solemn and so rare,

Since seldom coming in the long year set,

Like stones of worth they thinly placed are,

Or captain jewels in the carcanet.

So is the time that keeps you as my chest,

Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide,

To make some special instant special blest

By new unfolding his imprisoned pride.

Blessed are you, whose worthiness gives scope,

Being had, to triumph, being lacked, to hope.

We can readily interpret the imagery as sexual. Now, also, let’s look at part of a speech by the King in 1 Henry IV, addressing his son Harry, or Prince Hal, the future Henry V. In this case, certain words or forms of words – keep, robe, seldom, feast, rareness, solemnity – are used within an entirely different context, that is, in this history play the father is speaking to his royal son, explaining how he gained his subjects’ adoration by limiting his public appearances:

Thus did I keep my person fresh and new,

My presence, like a robe pontifical,

Ne’er seen but wondered at; and so my state,

Seldom but sumptuous, showed like a feast,

And won by rareness such solemnity. (3.2.53-59)

Those words of Henry IV need no other context than that of this play of royal history; the same words within the sonnet, however, are delivered without any such frame of reference. The sexual context may appear obvious, but Wells and Edmondson want us to believe it’s the only context.

Might Edward de Vere have written the entire numerical sequence of the Sonnets within another, much more important framework as well? One worthy to outlive “marble” and “the gilded monument(s) of Princes”? If he also wrote those lines to record the historical circumstances and events of political power and danger that both he and Henry Wriothesley faced, the Oxfordian case will prevail just as soon as readers are able to see it — regardless of any and all Stratfordian fantasies.