Following is a talk I gave to the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Conference on 17 October 2019 at the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, CT:

Part One

Samuel Clemens drew upon a wealth of personal experience in his work; and in his later years, he made the remark: “I could never tell a lie that anybody would doubt, nor a truth that anybody would believe.” Imagine old Sam on his porch out there and Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, laughing along with him. And Oxford reminding him what Touchstone said in As You Like It: “The truest poetry is the most feigning” – in other words, pretending — telling truth by allegory and a “second intention.” Both men knew that more truth can be told and believed when dressed as fiction, whether it’s Huckleberry Finn or Hamlet. And, of course, both men wrote under pen names.

(Dedication of “Venus and Adonis” in 1593 to Southampton with first printing of the Shakespeare name)

I want to talk first about the launch of the pen name “Shakespeare” in 1593, on the dedication of Venus and Adonis to Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, asking, “Who Knew What and When?” – or – “What Did They Know and When Did They Know It?” The question is posed in relation to five individuals.

Queen Elizabeth – Did her Majesty see the letter to her from early reader William Reynolds, saying she was the subject of a crude parody in the character of Venus? Did she know who had written this scandalous, instant bestseller? If she did know, when did she know it?

William Cecil Lord Burghley – Reynolds also wrote to the chief minister, saying he was offended by this portrait of Elizabeth as a “lusty old” queen. Meanwhile, Burghley was Southampton’s legal guardian and still pressuring him to marry his granddaughter, Elizabeth Vere (who may or may not have been the natural daughter of Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford). Therefore anything involving Southampton would be of great interest to Burghley and his rapidly rising son Robert Cecil.

After the death in 1590 of Francis Walsingham, head of the secret service, William and Robert Cecil had taken over the crown’s network of spies and informants. They made it their business to know everything; and now they were gearing up for the inevitable power struggle to control the succession upon Elizabeth’s death.

The queen refused to name her successor, even though she was turning sixty and could die any moment. The Cecils were preparing for the fight with Robert Devereuex, second Earl of Essex, with whom Southampton was closely allied. Could they allow this “Shakespeare” to dedicate to Southampton such a popular, scandalous work and not know the author? What did Burghley know and when did he know it?

Henry Wriothesley Lord Southampton, nineteen, whom we can imagine arriving at the royal court, where folks had their copies of Venus and Adonis with its dedication to him. Might they be curious about “William Shakespeare”? And about his relationship to Southampton? What did the earl know and when did he know it?

John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, who issued the publishing license in his own hand. He had a large staff for that purpose and normally delegated readings of manuscripts and signings-off on licenses, but now he took it upon himself. This strict archbishop was in charge of all government censorship. Why would he give his personal approval of such salacious poetry? Why would he allow this possibly dangerous political allegory into the market? Would he have done so without prior authorization from the queen and Burghley?

Whitgift had been appointed archbishop in 1583 and had gained her Majesty’s full trust and admiration. In 1586 he was given the authority to peruse and license all manuscripts and the power to destroy the press of any printer. He suppressed the Puritans so harshly that in 1588 they began to publish pamphlets against him, led by a writer using the pen name “Martin Marprelate” (who was “marring the prelates”). The archbishop responded with a ruthless campaign of retaliation, using pamphlets turned out by members of Oxford’s writing circle such as Tom Nashe and John Lyly. Apparently, the earl himself wrote against “Marprelate” under the pen name “Pasquil Cavaliero.” (One pen name battling another!)

At the end of the 1590s, the archbishop will issue a decree ordering the burning of a long list of books, among them several based on works of Ovid. The condemned books will be publicly burned in the infamous Bishops’ Bonfire of 1599, but none will include works attributed to “Shakespeare” — not even Venus and Adonis or Lucrece, both based on Ovid. (“Shakespeare” never got into trouble for his writing.) Now in 1593, Whitgift personally authorizes Venus and Adonis for publication by Field.

Richard Field, Publisher-Printer, who entered Venus and Adonis at the Stationer’s Register in April 1593.

Field will print Love’s Martyr in 1601 with The Phoenix and Turtle as by “William Shake-speare” — hyphenated, as if to confirm that it’s a pen name. (Presumably he was the son of Henry Field, a tanner in Stratford-upon-Avon; but modern researchers are finding it difficult to verify that presumption.) Regardless of his background, by age seventeen in 1579 he was in London. He apprenticed for several years under the esteemed printer and French refugee Thomas Vautrollier, who died in 1587. A year later Field married Vautrollier’s widow and, at twenty-six, he took over the publishing business.

He was a dedicated Protestant, committed to the policies of Queen Elizabeth. It’s been said Field was “Burghley’s publisher.” Later he would issue Protestant books in Spanish, for sale in Catholic Spain, under “Ricardo del Campo” – another pen name.

In 1589 Field published The Arte of English Poesie, by a deeply knowledgeable writer choosing not to identify himself. Along with Richard Waugaman and others, I hold the view that The Arte was written (wholly or in part) by Oxford, whose own verse is cited for description and instruction, not to mention that he himself is fulsomely praised as chief poet of the Elizabethan court.

The anonymous author of The Arte addresses his entire tract to Elizabeth – with distinct echoes of Oxford’s own praise of the queen in his elegant Courtier preface of 1572. The invisible author also uses the kind of alliteration Oxford so enjoyed; for example, he tells her Majesty:

“You, Madam, my most Honored and Gracious, if I should seem to offer you this my desire for a discipline and not a delight … By your princely purse, favours and countenance, making in manner what ye list, the poor man rich, the lewd well learned, the coward courageous, and the vile both noble and valiant: then for imitation no less, your person as a most cunning counterfeit lively representing Venus…”

(Here is Richard Field, who will publish Venus and Adonis four years later, issuing an anonymous book in which the author likens Queen Elizabeth to Venus.)

“Venus and Adonis” by Titian, the painting that “Shakespeare” must have seen in Venice (showing Adonis wearing his bonnet)

There is strong evidence that Oxford wrote the first version of Venus and Adonis in the latter 1570s after returning from Italy, where he had made his home base in Venice. For example, the poem contains a lifelike portrait-in-words of Venus trying to seduce young Adonis, who, significantly, is wearing his bonnet. Without question this section of the narrative poem is a vivid description of the painting in Venice at Titian’s own house, which Oxford must have visited (as most traveling nobles did) – because in that house was Titian’s only painting of Venus and Adonis (among his many others of the same subject) in which the young god is wearing his bonnet.

It may also be that Oxford was creating an allegory of his own experience as a young man pursued by Elizabeth. Adonis is killed by the spear of a wild boar — perhaps the same boar of Oxford’s earldom, as though his own identity is officially killed by the spear of “Shakespeare,” his new pen name. From the blood of Adonis, a purple flower springs up, and Venus tells it: “Thou art next of blood and ‘tis thy right.” Then the lustful goddess flies off to Paphus, the city in Cyprus sacred to Venus, to hide from the world. Her silver doves are mounted through the empty skies, pulling her light chariot and “holding their course to Paphus, where their Queen means to immure herself and not be seen.”

Oxford had an extensive personal history of publicly likening Queen Elizabeth to Venus. In Euphues and his England, the novel of 1580 dedicated to the earl, she is portrayed as both the Queen of Love and Beauty and the Queen of Chastity: “Oh, fortunate England that hath such a Queen! … adorned with singular beauty and chastity, excelling in the one Venus, in the other Vesta ….” — the sexual goddess and the virginal goddess, both at once.

In the Paradise of Dainty Devices (1576), the scholar Steven May writes, Oxford definitely likens Elizabeth to Venus: “But who can leave to look on Venus’ face?” the poet asks, referring to “her alone, who yet on th’earth doth reign.”

In the final chapter of Arte, the author apologizes to the queen for this “tedious trifle” and fears she will think of him as “the Philosopher in Plato who failed to occupy his brain in matters of more consequence than poetry,” adding, “But when I consider how everything hath his estimation by opportunity, and that it was but the study of my younger years in which vanity reigned…”

(“When I consider how everything” will be echoed in sonnet 15, which begins, “When I consider everything…”)

The anonymous author tells Elizabeth that “experience” has taught him that “many times idleness is less harmful than profitable occupation.” He refers sarcastically, sounding like Hamlet, to “these great aspiring minds and ambitious heads of the world seriously searching to deal in matters of state” who become “so busy and earnest that they were better be occupied and peradventure altogether idle.”

(Who else would dare to write that description to her Majesty about members of her own government? Oxford had written similar thoughts in his own poetry such as, “Than never am less idle, lo, than when I am alone.” At the same time, he pledges his “service” to her, according to his “loyal and good intent always endeavoring to do your Majesty the best and greatest of those services I can.” Oxford always talks about serving the queen, as he wrote to Burghley, “I serve her Majesty, and I am that I am.”)

Richard Field publishes this work of 1589, written by an anonymous author sounding much like Oxford, and containing some of the earl’s own work, praising him to the skies – and then Field dedicates it to Burghley. “This book,” he tells the most powerful man in England, “coming to my hands with his bare title, without any Author’s name or any other ordinary address, I doubted how well it might become me to make you a present thereof.”

He was surprised and mystified to see this manuscript just flying over the transom into his hands; however, seeing that the book is written to “our Sovereign lady the Queen, for her recreation and service,” Field publishes the work and even dedicates it to Burghley. In his dedication, he also sounds as if Oxford helped him, as when he writes alliteratively of “your Lordship being learned and a lover of learning … and myself a printer always ready and desirous to be at your Honorable commandment.”

Four years later Field publishes Venus and Adonis dedicated to Southampton, whom Burghley, with the queen’s blessing, hopes to gather into his own family. Even orthodox commentators recognize that the high quality of the printing suggests Shakespeare’s direct involvement, as Frank Halliday writes in A Shakespeare Companion: “The two early poems, Venus and Adonis and Lucrece, both carefully printed by Field, are probably the only works the publication of which Shakespeare personally supervised.” (Imagine the Earl of Oxford working side by side with Richard Field at his shop in Blackfriars, to fine-tune the printing!) Now the manuscript goes to Whitgift, chief censor for everything published in England, and he signs off in his own hand – a fact that Field quickly advertises in the Stationers Register.

The question is posed in relation to Publisher Richard Field, Archbishop John Whitgift, Queen Elizabeth, Lord Burghley and the Earl of Southampton: Who knew what and when? What did they know and when did they know it?

My answer is that they all knew about the launch of Oxford’s new pen name and knew it before this work was published. They each knew who “Shakespeare” was and they allowed the earl to publish it and dedicate it to Southampton. The very individuals who were most closely involved, with the most at stake, and could make such decisions, must have worked directly, or indirectly, with each other – and with the author himself – to launch the famous pen name.

Part Two

There is another dimension to the pseudonym that I would like to describe. It begins back in 1583, when Protestant England and Catholic Spain were definitely at war; and gearing up to defend against this mighty enemy was the queen’s great Puritan spymaster, Francis Walsingham, who quickly organized a new company of players. The Puritans generally hated the public theater, but Walsingham knew its value in terms of propaganda.

The new company, approved by Burghley and patronized by Elizabeth, was called the Queen’s Men. It was comprised of two separate troupes touring the country to rouse patriotic fervor and unity. All existing companies – including Oxford’s — contributed their best actors – and de Vere collected his expanding group of writers at a mansion in London (nicknamed Fisher’s Folly) for scribes such as Nashe, Lyly, Watson, Greene, Munday, Churchyard, Lodge and many others.

(Imagine Michelangelo’s studio filled with artists working together under a single guiding hand.)

In the 1580s these writers turned out dozens, even hundreds of history plays. Among them were Oxford’s own early versions of Shakespeare histories, anonymous plays such as The Troublesome Reign of King John, The True Tragedy of Richard Third, The True Chronicle History of King Leir and The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth, the latter containing the entire framework for Henry Fourth Parts One and Two and Henry the Fifth as by Shakespeare.

Their weapons were not swords or guns or ships, but words, giving birth to an inspiring new English language and vision of national identity – a powerful weapon that de Vere was creating and guiding as well as helping to finance. And in 1586 the queen rewarded him with an extraordinary annual allowance of a thousand pounds, paid according to the same formula used to finance Walsingham for his wartime secret service. When the Spanish invasion by Armada arrived in 1588, volunteers from all parts of England responded – Protestants, Puritans, Catholics, speaking different dialects and often needing to be translated, all joining in the face of a common enemy.

Once the Great Enterprise of King Philip had been turned back, however, that same government had no more use for the writers. Having harnessed their talent and work to touch the minds and hearts of the queen’s subjects, the government now became wary of them, perhaps afraid of their freedom of expression and power to influence her Majesty’s subjects.

After defeating the enemy without, the government now focused upon its real or potential enemies within. The end game of internal power struggles was just beginning. Who would gain control of the inevitable succession to Elizabeth? Oxford had been the central sun from which the writers had drawn their light, and around which they had revolved; but now he was deliberately squeezed with old debts and could no longer support them, so they began to fly out of orbit and disappear.

By 1590, the year Walsingham died, Oxford’s secretary and stage manager John Lyly was out of a job; in 1591, Thomas Lodge escaped poverty by sailing to South America; in September 1592, Thomas Watson died and so did Robert Greene (if, in fact, Greene was a real person and not another pen name); on 30 May 1593, Christopher Marlowe was stabbed to death; later that year, Thomas Kyd was tortured on the rack, leading to his death.

Lyly, Lodge, Watson, Greene, Marlowe, Kyd: all gone. They disappeared in a kind of bloodbath, into a metaphorical graveyard of writers; and Oxford himself disappeared. He withdrew from court and vanished from London. He remarried (his first wife, Anne Cecil, had died in 1588) and became something of a recluse at Hackney – undoubtedly revising his previous plays.

As far as the general public knew, Oxford no longer existed; some people even thought he was dead; but in the spring of 1593, just when Marlowe was being murdered, something else was afoot. From below the graveyard of writers, without any paper trail or personal history, the heretofore unknown “William Shakespeare” – a disembodied pen name — suddenly rose in defiance, shaking the spear of his pen and asserting his power in the Latin epigraph from Ovid on the title page of Venus and Adonis, translated as: “Let the mob admire base things! May Golden Apollo serve me full goblets from the Castilian Spring!” Who is this Shakespeare? And which side is he on?

The sudden appearance of this name was not on the title page, but, rather, inside the book, and linked (directly, and uniquely) to nineteen-year-old Southampton. And in the very next year, 1594, the poet made himself even clearer, dedicating Lucrece to Southampton: “The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end … What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours, being all I have, devoted yours.” All that the pen name has is a multitude of written works to be published under that name – the two poems, plus any other writings that will use “Shakespeare” in the future.

A metamorphosis has taken place. In this second dedication, the pen name is speaking for itself and not, in the first place, for the Earl of Oxford, who has disappeared; the pen name is saying to young Lord Southampton: “ALL I HAVE – ANYTHING WRITTEN UNDER THIS NAME — IS NOW AND FOREVER DEVOTED TO YOU. THEY ARE YOURS, TO DO WITH WHAT YOU WILL.” It is all “YOURS … YOURS … YOURS.”

The disembodied pen name has declared itself on the side of the young nobility, in favor of the Essex faction of which Southampton is a prominent member. Soon that young earl firmly and finally rejects Burghley’s marriage plans for him. Essex has been in secret communication with James in Scotland – pledging his support for the King, in return for the promise of James’ help against Burghley and his son Robert Cecil.

So long as Elizabeth remains alive, she can still name her successor; meanwhile, a main goal of Essex and Southampton is to keep the Cecils from assuming even more power after she dies. We are now in the very short period spanning 1595 to 1600 – six years – in which the great issuance of Shakespeare plays occurs: earlier plays that are now revised for the printing press and the public playhouse.

Robert Cecil becomes Principle Secretary in 1596; in the following year, he tries to have all public playhouses shut down and nearly succeeds; in fact, he does succeed in destroying the Swan Playhouse as a venue for plays.

And upon the death of his father, Burghley, in August 1598, Secretary Cecil begins to gain the full trust of Her Majesty and the power to control her mind, emotions and decisions. Now the gloves come off and “Shakespeare” suddenly – for the first time — makes its appearance on printed plays. Over the next three years comes the historic rush of quartos. In 1598 and 1599, four plays are printed with “Shake-speare” hyphenated, emphasizing it’s a pen name: Love’s Labour’s Lost, Richard III, Richard II and 1 Henry IV. The playwright had “newly corrected” two of these plays, quite obviously having written them their first versions much earlier.

Four more plays are published in 1600, all using the pen name without any hyphen: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2 Henry IV, The Merchant of Venice and Much Ado About Nothing. And three others also appear in that time frame, but still anonymous: Romeo and Juliet, 3 Henry VI, and Henry V. Many of these plays – especially the histories – deal with issues of kingship, of what kind of monarch should or should not rule, the right and wrong ways to choose a successor, the consequences of deposing a rightful king. These issues are swirling on and off the stage, in allegory and in real life, all around the aging queen, who refuses to make a choice while she still has the strength to do so.

Edward, Earl of Oxford was summoned as a judge to the 1601 trial of Essex and Southampton — the same Southampton to whom “Shakespeare” had pledged his “love … without end.”

Southampton takes charge of planning an assault on Whitehall Palace, aiming to remove Cecil and confront Elizabeth without interference. If they gain entrance to her presence, they will beg the queen to fulfill her responsibility by choosing a successor.

Members of the Essex faction meet with the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, Shakespeare’s company, paying the actors to give a special performance of Richard II at their own playhouse, the Globe, on Sunday 7 February 1601. Southampton is in charge of the Shakespeare plays and, most likely, he himself pays for the performance – with its deposition scene of King Richard handing over his crown to Bolinbroke, who becomes Henry IV.

(The play is instructional. It’s also a cautionary tale: Richard is murdered in prison by Pierce of Exton, who mistakenly believes he’s carrying out the king’s wishes.)

Cecil uses this performance to summon Essex that night and trigger the chaotic events of the following day. By midnight of the Eighth of February, Essex and Southampton are both arrested and taken by river through Traitors Gate into the Tower, facing charges of high treason and almost certain execution. Of course, this play of royal history is another allegory, and Elizabeth will famously cry out six months later, “I am Richard the Second, know ye not that?”

So long as Southampton is in the prison, there will be no authorized printings of new Shakespeare plays. In effect, the pen name goes silent. The actors of Shakespeare’s company are summoned for questioning, but never the author … but why not? Well, he can’t be summoned, can he? He has no flesh and blood, because “Shakespeare” — after all – is but a pen name.

Postscript

While Southampton languishes in prison, another metamorphosis takes place, as recorded by Oxford in the Sonnets. First, his disappearance: “My name be buried where my body is” (72); and “I, once gone, to all the world must die” (81). Then his sacrifice to the pen name, in a sequence that traditional critics call the Rival Poet series. The true “rival,” however, is not a flesh-and-blood person; rather, it is Oxford’s own pseudonym on the printed page.

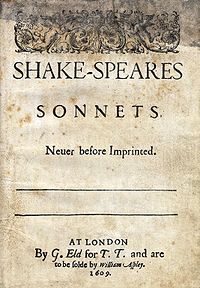

Oxford understood that “Shakespeare” would remain attached to Southampton, even as he himself, the true author, faded from the world’s view. The Sonnets would be suppressed upon their publication in 1609, and the quarto would remain underground for more than a century until it reappeared in 1711, like a message in a bottle, carrying Oxford’s true account for posterity. The story — of how Oxford sacrificed himself to save Southampton’s life and gain his freedom — remains within the “monument” of the Sonnets:

“Your monument shall be my gentle verse,/ Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read” (81); “And thou in this shalt find thy monument,/ When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent” (107).