Two books devoted entirely to Shakespeare’s knowledge and treatment of heraldry are The Heraldry of Shakespeare: A Commentary with Annotations (1930) by Guy Cadogan Rothery and Shakespeare’s Heraldry (1950) by Charles Wilfred Scott-Giles. They show that the Bard knew a great deal about coats of arms, blazons, charges, fields, escutcheons (shields), crests, badges, hatchments (panels), gules (red markings or tinctures) and much more.

But it’s not simply that Shakespeare has considerable knowledge about heraldry; it’s that such knowledge is an integral part of his thought process. He uses heraldic terms in spontaneous, natural ways, often metaphorically, making his descriptions more vivid while stirring and enriching our emotions.

Take, for example, the word badge, which in heraldry is an emblem indicating allegiance to some family or property. Shakespeare uses it literally, of course, but also metaphorically: Falstaff in 2 Henry IV speaks of “the badge of pusillanimity and cowardice” (4.3); Ferdinand in Love’s Labour’s Lost cries out, “Black is the badge of hell” (4.3); Lysander in in A Midsummer Night’s Dream talks about “bearing the badge of faith” (3.2); Tamora in Titus Andronicus declares, “Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge” (1.1); and in Sonnet 44 the poet refers to “heavy tears, badges of either’s woe.”

Surely this author was “one of the wolfish earls,” as Walt Whitman perceived, a proud nobleman for whom hereditary titles, shields and symbols were everyday aspects of his environment. From early boyhood, Edward de Vere had been steeped in the history of his line dating back five hundred years to William the Conqueror; the heraldry of his ancestors, as well as that of other noble families, became interwoven with his vocabulary.

Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream extends the metaphor of two bodies sharing the same heart by presenting the image of a husband and wife’s impaled arms: “So, with two seeming bodies, but one heart; two of the first, like coats in heraldry, due but to one and crowned with one crest” (3.2)

Another example of “Shakespeare” thinking and writing in heraldic terms occurs in the opening scene of 1 Henry VI, at the funeral of Henry V at Westminster Abbey. A messenger warns the English against taking recent victories for granted by describing setbacks in France as the cropping (cutting-out) of the French quarters in the royal arms of England:

“Awake, awake, English nobility! Let not sloth dim your honors new-begot: cropped are the flower-de-luces in your arms! Of England’s coat one half is cut away!”

England’s coat of arms presented flower-de-luces or fleur-de-lis, the emblem of French royalty, quartered with Britain’s symbolic lions. Cropping the two French quarters would cut away half the English arms – a vivid description of England’s losses in France.

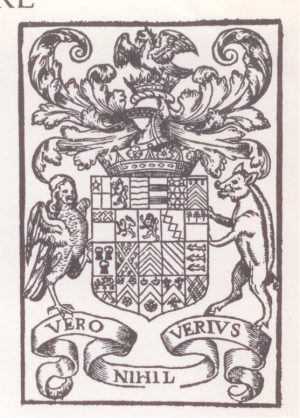

“The Vere arms changed repeatedly over many generations,” the late researcher Robert Brazil noted, adding that details of Oxford’s arms had “numerous documented precedents” consisting not only of drawings but also the “blazonry” or descriptions of shields in precise heraldic language, using only words. “Through the science of blazon, infinitely complex visual material is described in such a precise way that one can accurately reproduce full color arms with dozens of complex coats, based on the words of the blazon alone.”

At the Vere seat of Castle Hedingham, the young earl necessarily studied the seals and tombs of his ancestors. He, after all, was a child of the waning feudal aristocracy, set to inherit the title of Lord Great Chamberlain of England. To assert the rights and rankings of his Vere identity, he needed exact knowledge of his family’s heraldry and to “blazon” or describe it in words through the five centuries of its history.

“Shakespeare” uses “blazon” just as we might expect it to be employed by de Vere, that is, as a natural enrichment of language. Mistress Quickly in The Merry Wives of Windsor employs the word in a burst of heraldic imagery:

“About, about; search Windsor Castle, elves, within and out … Each fair installment, coat, and several crest, with loyal blazon, evermore be blest!” (5.5)

Oxford knew Windsor Castle well; he is recorded as staying there several times. At nineteen he lodged in a hired room in the town of Windsor while recovering from illness.

Mistress Quickly refers to each “installment” in the castle, that is, each place where an individual knight is installed. The knight’s “coat” was on a stall-plate nailed to the back of the stall and the “crest” was a figure or device originally borne by a knight on his helmet.

From the same pen we find “blazon” in a variety of metaphorical contexts:

“I’faith, lady, I think your blazon to be true” – Much Ado About Nothing (2.1)

“Thy tongue, thy face, thy limbs, actions and spirit do give thee five-fold blazon” – Twelfth Night (1.5)

“But this eternal blazon must not be to ears of flesh and blood” – Hamlet (1.5)

In Sonnet 106 the poet uses “blazon” in the context of accounts of medieval chivalry, writing of “beauty making beautiful old rhyme / In praise of Ladies dead and lovely Knights,” followed by: “Then in the blazon of sweet beauty’s best,/ Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow,/ I see their antique Pen would have expressed/ Even such a beauty as you master now.”

In Hamlet the prince tells the players that a speech he “chiefly loved” was the one that Virgil’s Aeneas delivers to Dido, Queen of Carthage, about the fall of Troy. Before the first player can begin to recite it, however, Hamlet delivers thirteen lines from memory — describing how Pyrrhus, son of the Greek hero Achilles, had black arms while hiding inside the Trojan horse; but then his arms became drenched in the red blood of whole families that were slaughtered.

The story had even greater impact upon aristocratic members of the audience who knew the bloody tale was being told in the context of heraldic terms, such as “sable arms” (the black device displayed on Pyrrhus’ shield); “gules” (red); and “tricked” (decorated), not to mention that Pryrrhus’ arms, covered with red blood, are “smeared with heraldry”: (+see below)

The rugged Pyrrhus, he whose sable arms,

Black as his purpose, did the night resemble

When he lay couched in the ominous horse,

Hath now this dread and black complexion smeared

With heraldry more dismal. Head to foot

Now is he total gules, horridly tricked

With blood of fathers, mothers, daughters, sons…(Hamlet, 2.2)

Even Lucrece (1594), the second publication as by “Shakespeare,” is filled with heraldic imagery:

But Beauty, in that white entitled

From Venus’ doves, doth challenge that fair field...

This heraldry in Lucrece’s face was seen… (Stanzas 9 & 10, emphases added)

(“Challenge”: lay claim to; “field”: the surface of a heraldic shield on which figures or colors are displayed, but also evoking a battlefield)

Brazil notes that previous earls of Oxford had employed a special greyhound as a heraldic symbol, but that Edward had stopped using it; in the opening scene of Merry Wives, which begins and ends with humorous dialogue involving heraldry, there’s a line (unrelated to anything else) about a “fallow” greyhound, one that is no longer used:

Brazil notes that previous earls of Oxford had employed a special greyhound as a heraldic symbol, but that Edward had stopped using it; in the opening scene of Merry Wives, which begins and ends with humorous dialogue involving heraldry, there’s a line (unrelated to anything else) about a “fallow” greyhound, one that is no longer used:

Page: I am glad to see you, good Master Slender.

Slender: How does your fallow greyhound, sir?

In this “throwaway” exchange, is de Vere, pointing to his own heraldic history?

+ Earl Showerman writes: “The source of of the term ‘pyrrhic victory’ is historical not mythopoetic. King Pyrrhus of Epirus defeated the Romans at Heraclea in 280 BC, but the victory cost him so dearly he had to withdraw his invasion of Italy because the Romans were quickly resupplied with fresh troops. Pyrrhus in Homer is of the same nature, to be sure, and his sin of slaughtering Priam at the family shrine was the primary cause of the difficulties incurred by all the Greeks in getting home from Troy.”

(This post is now No. 64 of 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford, as edited by Alex McNeil with other editorial help from Brian Bechtold.)