A coat-of arms used by Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford – with his motto “Vero Nihil Verius” or Nothing Truer than Truth

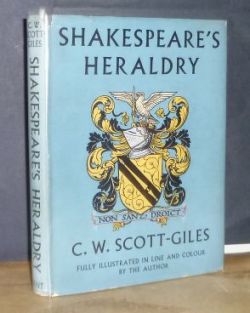

At least three books are devoted entirely to Shakespeare’s knowledge and treatment of heraldry. Two of them are The Heraldry of Shakespeare: A Commentary with Annotations (1930) by Guy Cadogan Rothery and Shakespeare’s Heraldry (1950) by Charles Wilfred Scott-Giles; and on this basis alone, the bard must know a great deal about coats of arms, blazons, charges, fields, escutcheons (shields), crests, badges, hatchments (panels), gules (red markings or tinctures) and much more.

But it’s not simply that Shakespeare has considerable knowledge about heraldry; in fact, it’s part of his thought process. He uses heraldic terms in spontaneous, natural, unforced ways, often metaphorically, making his descriptions more vivid while stirring and enriching our emotions.

Take, for example, the word badge, which in heraldry is an emblem indicating allegiance to some family or property. Shakespeare uses it literally, of course, but also metaphorically: Falstaff in Henry IV Part Two speaks of “the badge of pusillanimity and cowardice”; Ferdinand in Love’s Labour’s Lost cries out, “Black is the badge of hell”; Lysander in in A Midsummer Night’s Dream talks about “bearing the badge of faith”; Tamora in Titus Andronicus declares, “Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge”; and, using his own voice, the poet refers in Sonnet 44 to “heavy tears, badges of either’s woe.”

Surely this great author was “one of the wolfish earls,” as Walt Whitman so readily perceived – a proud nobleman for whom hereditary titles, shields and symbols were everyday aspects of his environment. From early boyhood, Edward de Vere the seventeenth Earl of Oxford had been steeped in the history of his line dating back five hundred years to William the Conqueror; the heraldry of his ancestors, as well as that of other noble families, became interwoven with his vocabulary.

[Need I add that this is not reported out of snobbery or some kind of preference for the upper class? Having begun my professional life as a journalist, I can state that everything in this blog comes from an attempt to look at the evidence — as opposed to the myth — and to write what I see.]

Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream extends the metaphor of two bodies sharing the same heart by presenting the image of a husband-and-wife’s impaled arms: “So, with two seeming bodies, but one heart; two of the first, like coats in heraldry, due but to one and crowned with one crest.”

An example of “Shakespeare” thinking and writing in heraldic terms occurs in the opening scene of Henry VI Part Two, upon the funeral of Henry the Fifth at Westminster Abbey. A messenger warns the English against taking recent victories for granted by describing setbacks in France as the cropping (cutting-out) of the French quarters in the royal arms of England: “Awake, awake, English nobility! Let not sloth dim your honors new-begot: cropped are the flower-de-luces in your arms! Of England’s coat one half is cut away!”

(England’s coat of arms presented flower-de-luces or fleur-de-lis, the emblem of French royalty, quartered with Britain’s symbolic lions. Cropping the two French quarters would cut away half the English arms – a vivid description of England’s losses in France.)

“The Vere arms changed repeatedly over many generations,” the late Oxfordian researcher Robert Brazil noted, adding that details of Edward de Vere’s arms had “numerous documented precedents.”

Such documentation consisted not only of drawings but also the “blazonry” or descriptions of shields in precise heraldic language, using only words. “Through the science of blazon,” Brazil wrote, “infinitely complex visual material is described in such a precise way that one can accurately reproduce full color arms with dozens of complex coats, based on the words of the blazon alone.”

At the Vere seat of Castle Hedingham in Essex, the young Earl of Oxford necessarily studied the seals and tombs of his ancestors. He, after all, was a member of the old feudal aristocracy; he would inherit the title of Lord Great Chamberlain of England, raising him to become the highest-ranking earl of the realm. To assert the rights and rankings of his Vere identity, he needed exact knowledge of his family’s heraldry and to “blazon” or describe it in words through the five centuries of its history.

“Shakespeare” uses “blazon” just as we might expect it to be employed by Edward de Vere, that is, as a natural enrichment of language. Mistress Quickly in The Merry Wives of Windsor, near the end of the play, employs the word in a burst of heraldic imagery: “About, about; search Windsor Castle, elves, within and out … Each fair installment, coat, and several crest, with loyal blazon, evermore be blest!”

[Oxford knew Windsor Castle well; he is recorded as staying there several times; and at age nineteen, he lodged in a hired room in the town of Windsor while recovering from illness.]

Mistress Quickly refers to each “installment” in the castle, that is, each place where an individual knight is installed; the knight’s “coat” was on a stall-plate nailed to the back of the stall; and the “crest” was a figure or device originally borne by a knight on his helmet.

From the same pen we find “blazon” in a variety of metaphorical contexts: “I’faith, lady, I think your blazon to be true” – Much Ado About Nothing; “Thy tongue, thy face, thy limbs, actions and spirit do give thee five-fold blazon” – Twelfth Night; “But this eternal blazon must not be to ears of flesh and blood” – Hamlet; and in Sonnet 106 to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton he uses “blazon” in the context of accounts of medieval chivalry, writing of “beauty making beautiful old rhyme / In praise of ladies dead and lovely knights,” followed by: “Then in the blazon of sweet beauty’s best,/ Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow,/ I see their antique pen would have expressed/ Even such a beauty as you master now.”

In Hamlet the prince tells the players that a speech he “chiefly loved” was the one that Virgil’s Aeneas delivers to Dido, Queen of Carthage, about the fall of Troy. Before the first player can begin to recite it, however, Hamlet delivers thirteen lines from memory. In these lines he describes how Pyrrhus, son of the Greek hero Achilles, had black arms while hiding inside the Trojan horse; but then his arms became drenched in the red blood of whole families that were slaughtered. (Such was the origin of “Pyrrhic victory” to describe a success at too great a cost. – NOT! SEE CORRECTION IN COMMENTS SECTION FROM EARL SHOWERMAN.)

But the story had even greater impact upon members of the audience who knew that the bloody tale was being told in the context of heraldic terms – such as sable arms (the black device displayed on Pyrrhus’ shield); gules (red); and tricked (decorated), not to mention that Pryrrhus’ arms covered with red blood are “smeared with heraldry”:

The rugged Pyrrhus, he whose sable arms,

Black as his purpose, did the night resemble

When he lay couched in the ominous horse,

Hath now this dread and black complexion smeared

With heraldry more dismal. Head to foot

Now is he total gules, horridly tricked

With blood of fathers, mothers, daughters, sons…

Even the narrative poem Lucrece (1594), the second publication as by “Shakespeare,” is filled with heraldic imagery:

But Beauty, in that white entitled

From Venus’ doves, doth challenge that fair field…

This heraldry in Lucrece’s face was seen… (Stanzas 9 & 10)

(Challenge: lay claim to; field: the surface of a heraldic shield on which figures or colors are displayed, but also evoking a battlefield; from world’s minority: from the beginning of time)

Robert Brazil noted that previous earls of Oxford had employed a special greyhound as a heraldic symbol, but that Edward, the seventeenth earl, had stopped using it; and that in the opening scene of The Merry Wives of Windsor (which begins and ends with humorous dialogue involving heraldry) there’s a line, unrelated to anything else, about a “fallow” or no-longer-used greyhound:

Robert Brazil noted that previous earls of Oxford had employed a special greyhound as a heraldic symbol, but that Edward, the seventeenth earl, had stopped using it; and that in the opening scene of The Merry Wives of Windsor (which begins and ends with humorous dialogue involving heraldry) there’s a line, unrelated to anything else, about a “fallow” or no-longer-used greyhound:

PAGE: I am glad to see you, good Master Slender.

SLENDER: How does your fallow greyhound, sir?

In this otherwise meaningless “throwaway” exchange, is there a little wink from Edward de Vere, pointing to his own heraldic history?

Whittemore, there was a boar in Oxford’s coat. Do you think that boar is the same of “Venus and Adonis”? Maybe you don’t know, but in 1611 was published a version of “The Faerie Queen” by Edmund Spenser. I believe in Ricardo Mena when he says that John Donne used Spenser as a pseudonym and was an apprentice of Oxford. I saw in the 1611 edition of “The Faerie Queen” a man and a woman next to title, whom clothes may indicate and aristocrate position of both. under the title, we have and ilustration: we have a boar next to a rosebush and in this same rosebuch an Latin phrase saying “NON TIBI SPIRO” (something like “I smell not for thee”?). According to Mena, Prince Arthur isn’t Leicester like critics say but Oxford. Then, the man and woman of the title, to me, are Oxford and Elizabeth as well the boar and the rosebuch are reference to them (Oxford’s coat and Elizabeth’s Tudor Rose). Curiously, there is another boar in this same edition above the title. I want to ask you’re opinion about this if you can answered.

Francisco, I believe the boar in Venus and Adonis, although in the original Ovid story, represents Oxford, who was Adonis as well. In effect Oxford writes of his own “death” in relation to the birth of the little purple or royal flower, Southampton. He kills himself as Oxford was doing by taking the pen name Shakespeare at this time for the “first heir” of his invented name. The first heir is the poem itself and, as well, his royal son. The poem represents the birth of the purple flower; its publication represents the public birth, so to speak, of Southampton.

I don’t know about the boar in the Spenser edition. Mena is right that the Fairie Queen was the work of someone other than Spenser in Ireland. He may be right about John Donne, but overall I would think that Oxford must have been involved in this creation of Gloriana.

Well, he and Donne could have wrote together “The Faerie Queen”. I have already read that Oxford could have been both Nashe and Spenser (I saw this in some coments by Ricardo Mena). Then, he said that John Donne was the perfect candidate to Nashe’s and Spenser’s authorship. Though he was very young when this poets appeared, Donne had a very good education and like aristocrats youths, he started to write very good and erotic poetry and prose very young. After all, his uncle (whom name I can’t remeber) called him “my Wonderkid” because of his inteligence. I had already read that Bacon himself was the author of Thomas Nashe’s and Edmund Spenser’s work and a co-author with Oxford in Shakespeare’s plays.

If Donne really know Oxford and he was somekind of master or secret protector to him, then maybe Donne knew his darkest secrets. “The Choice of Valentine” by Nashe have a sonnet dedicating the poem to “Lord S.” (very probably Southampton). The sonnet’s first two verses says “Pardon, sweet flower of matchless poetry/And fairest bud that the red rose ever bare”. Donne used Oxford’s double image here. The “flower of matchless poetry” is Southampton, that is son (“flower”) of Oxford-Shakespeare (“matchless poetry”, the poem was ended in 1593, when Shakespeare appeared and get his fame as a very good erotica poet with “Venus and Adonis”). “Fairest bud that the red rose ever bare” indicates Southampton’s royal blood, Elizabeth as the “Rose” and Edward de Vere have his last name in the anagram “ever”.

Then, Donne knew certainly the secret of Southampton’s royal blood and maybe he didn’t need Oxford’s help to represent Elizabeth as Gloriana, who is always protected by Prince Arthur-Oxford, in “The Faerie Queen”.

The source of of the term ‘pyrrhic victory’ is historical not mythopoetic. King Pyrrhus of Epirus defeated the Romans at Heraclea in 280 BC, but the victory cost him so dearly he had to withdraw his invasion of Italy because the Romans were quickly resupplied with fresh troops. Pyrrhus in Homer is of the same nature, to be sure, and his sin of slaughtering Priam at the family shrine was the primary cause of the difficulties incurred by all the Greeks in getting home from Troy.

Ha! And I thought I was being so smart! So smart that I didn’t even have to look it up!:-) Thank you, Earl!

Hi Hank,

as far as i can remember there was a kind person commenting one of your reasons, who made a remark on the french translation of ‘ere long’. As in this above mentioned sonnet’s last line there is ‘ere long’, it might be deliberate, don’t you think so? I think you were really enthusiastic about that remark, I reckon it was rather important, something about de Vere / Oxford.

Double-thinking it, it’s really interesting. It was something like de Vere’s name or motto in french. And if it should be so, then the last line, which is this:

‘And better lines ere long shall honour thee’

should read:

‘And better lines de Vere shall honour thee’

Well, I’m just curious what your opinion is 🙂

Hi Sandy. I believe I was talking about the final line of 73 – “To love that well which thou must leave ere long,” with “leave ere” giving the sound of “l’hiver,” the French for winter (appropriately enough) and plays upon the name Ver or Vere. It’s an amazing combination of winter, to which the sonnet is leading, and his identification of himself. It makes me think of “The Winter’s Tale,” which I think, in the French translation, would include ‘l’hiver’ and so give us The Vere Story.

You identify two words “ere long,” in which other sonnet?

Thanks for brining it up, because for the first time I realize that “leave ere” also = “leave heir”

Curious. It’s just not “winter” in french that might indicate Oxford as Shakespeare. Oxford was influent in Latin, too. “Ver” in Latin means “Spring”. Is there some Shakespeare’s quote about spring that could indicating somekind of pun?

In sonnet 82, which is the “rival” series, and I believe in reference to his pen name, and elaborately writing in 1601 about his deal to bury his name behind the mask of Shakespeare, he writes:

The dedicated words which writers use

Of their fair subject, blessing every book

“The dedications that ‘Shakespeare’ used

About the fair youth, Southampton, blessing E.Ver’s two books”

In Love’s Labour’s Lost at the end we have “Ver, begin.”

Hi Hank,

maybe I wasn’t clear: ‘ere long’ can be found in the last line of the ‘Lord S.’ sonnet:

‘And better lines ere long shall honour thee.’

Ricardo Mena has a very good take on Choice of Valentines.

Shakespeare uses “ere long” fourteen times in the works.

What do we know of Nashe for sure?

Could “ere long” be a favorite phrase of the author, a conscious or unconscious signature?

To the right honourable, the Lord S.

Pardon, sweet flower of matchless poetry,

And fairest bud the red rose ever bare,

Although my muse, divorced from deeper care,

Presents thee with a wanton elegy;

Ne blame my verse of loose unchastity

For painting forth the things that hidden are,

Since all men act what I in speech declare,

Only induced by variety.

Complaints and praises every one can write,

And passion out their pangs in stately rhymes,

But of love’s pleasures none did ever write

That hath succeeded in these latter times.

Accept of it, dear Lord, in gentle gree,

And better lines ere long shall honour thee.

“But of love’s pleasures none did ever write

That hath succeeded in these latter times.”

Well, if it was written around 1593, when Oxford succeeded the first time, then it’ true that:

Ever (Vere) write that hath succeeded in these latter times.

Hm?

I think it’s a reference to “Venus and Adonis”. It was a best-seller in 1953, the same year when “Choices of Valentine” was finished and began circulating as manuscripts. Donne as Nashe wasn’t refering to himself in this sonnet nor in that two verses. He was refering to the same man he honoured later in his “Faerie Queene”, Edward de Vere, the earl of Oxford. He was refering to his “master” as Shakespeare by speaking of his “Venus and Adonis”, an (almost) epic and erotic poem that debates on love and lust. “The Choices of Valentine” is only about a youth who wants to lose is sexual purity and repents of it when he almost get the orgasm. Leaving the prostitute that was paid to give him pleasure, she mocks with men by calling them “fickle” and comparing them to a dildo. Nashe-Donne’s poem it’s too much erotic and lustfull to be “love’s pleasures (…) write” tough not such is “Venus and Adonis”.

Whittemore, you’re right. “this side, VER, the Spring”. It’s a pun with english and latin words that in portuguese is “Primavera” ;). Can Spring and Winter speaking be Oxford and Elizabeth?

Hi Hank,

this is just a play, but why not? You asked: ‘ere long’ could be a signature of Oxford? Well, I’ve found a meaning of it, which I’ll never prove, but between ourselves it might be interesting 🙂

‘Ere’ more than probably refers to Vere, that’s not new.

Long – it might be considered as an abbreviation. The following part-sentence can be found in The Arte of English Poesie (1589):

‘…, of which number is first that noble Gentleman, Edward Earle of Oxford’

LONG: Lord Oxford, Noble Gentleman

Hi Sandy,

I think thats important. Now we can read the verse “And better lines ere long shall honour thee” like “And better verses [Shakespeare’s] [Edward de] Vere, Lord Oxford [a] Noble Gentleman, shall honour you [Sothampton, his son].

If Donne knew is “master’s” tricks and puns to make “ere long” as “Vere, Lord Oxford Noble Gentleman”, could Oxford used this kind of acronym to Southampton in Sonnet 20?

“A man in HEWS and all HEWS in his controlling”

The word “hews” make not very sense so critics and students have used “hues” to substituted “hews”. But if we follow that Donne was using Oxford’s puns (wich inclued making commun words acronyms), then maybe HEWS in Sonnet 20 makes sense if we see it as an acronym of “Henry Earl Wriothesley Southampton”. It’s just my opinion…

It may also well be important. Just one remark: in the Quarto the first one is just hew, with ‘normal’ letters. The second one is capitalized Hews, and in italic.

An error of mine, Sandy :P. But the first “hew” of the verse doesn’t have the H capitalized as the second “Hews” have. And yes, in 1609 Quarto, “Hews” is in italic. Words capitalized and italicized in 1609 Quarto indicates a second meaning, like in Sonnet 1 “Beauty’s Rose”. The H capitalized in the italicized “Hews” may indicates a proper name like “Henry” or “Harry”.

Surely the Hews = Henry Wriothseley Southampton as you both say. Also I believe the “Mr. W.H.” of the dedication is not only a reversal of Southampton’s title (Lord) and name or initials (H.W.), but also a signal guiding us to the fact that the heart of the Sonnets monument is the prison time (1601-1603) of Southampton in the Tower, when he had been reduced to Mr. Henry Wriothesley or the “late” earl. Oxford probably composed the dedication himself, possibly while Southampton was still in the Tower, so that the “Mr.” was not a lie or a slander but a fact of Southampton’s existence at that time. In any case it’s a guide to the important story told by the sonnets.

It now occurs to me, for the first time, that Oxford’s salute in Sonnet 26 to “Lord of My Love” is not only the beginning of the epistle or end-stop for Sonnets 1-26 but intended to signal Southampton’s high stature by blood, i.e., Oxford’s liege-lord, ruler, to emphasize the dramatic fall in Sonnet 27 to begin the prison series, when he is an earl or lord or lord-liege no longer. (Instead he becomes a “jewel hung in ghastly night,” an incredible image.)

If we follow your logic that Oxford use many words with double meaning in the Sonnets, then “Lord of my Love” would be also like “Possessor of my blood”, shortly, “My son/My king”. In Sonnet 26, “Lord of my Love, to whom in vassalage/Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit” is “My son/My king, because I serve you, your true right to be king is bond to my pen-name (Shake-Speare; because, through this pseudonym, Edward had the duty to reveal Southampton’s royal blood).

The same does happen in Sonnet 20. “Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their pleasure” is “You have my blood/You are my son and the use you give of such royal blood [inherit Elizabeth’s throne or give continuation to Tudor Dinasty?] be their fate”.

But yet, Whittemore, I need your help to make an analysis to Sonnet 20. Can you help me?

I love English-majors, but they have a distressing tendency to read modern times into historic works. In modern times heraldic enthusiasts come in basically three flavors: hobbyists, titled nobleman, and hobbyists claiming to be titled nobleman.

In Shakespeare’s day everybody would have been familiar with heraldry. Literally everybody. Just as modern Americans (who don’t know what a Canton is) know the symbol of the their country has 50 stars on the Canton for the 50 states, and that the fly has 13 stripes for the 13 colonies; anyone in Elizabethan England could have told you the symbol of their country was the ancient arms of England quartered with France.

Heck, many families that we would consider moderately successful small businessman today adopted their own coats of arms. The Heraldic Visitations took place from 1530-1688, and were intended to force people to officially register such coats of arms.

Shakespeare’s family would actually have been eligible for arms, because his father was an Alderman. Even if his father refused to teach young William much things on principle, the fact that Shakespeare was an artist pretty much required him to learn about blazons. The way you made money as an artist of those days was selling to nobleman.

Thanks. All true. I still feel that “Shakespeare” uses heraldic terms as if they are an integral part of his vocabulary, and that this is more likely to come from the earl rather than from Shaksper of Stratford — but I can’t prove that and appreciate your comments here.

Neither all the aristocrats of the time were sufficiently versed in the heraldic lore (it is enough to recall the poor Earl of Surrey easily fooled by the fabricated heraldry-related charge), nor the artists and other servants were ignorant as to the “noble science” (even if not armigers themselves, they often offered various services, including the heraldry-related ones, to the armigers). The paper is absolutely unconvincing. Even more, it shows how the witty, enthusiastically life-exploring brand-new armiger W’m Shakespeare was gladly playing with the newly achieved pieces of knowledge.

True enough. See my reply to Nick Benjamin below. Again, the comment is much appreciated.

Interesting take on Surrey. I guess he put up a pretty weak defense against the fabricated charge, eh? Was it really fabricated?

I recall reading B.M. Ward’s 1928 documentary biography of Oxford and finding, near the end, Oxford’s formal request to serve at James’ coronation. He drew upon all the rights and privileges of his ancestors. Having been raised as Catholic, I felt a real similarity to religious rites. Clearly this stuff was sacred to him. I just looked it up. It’s very meticulous, and: “He also asks that he should have the same privileges as his ancestors who from time immemorial served the noble progenitors of our Lord the King with water before and after eating the day of the Coronation, and had as their right the basins and towels and a tasting cup, with which the said progenitors were served on the day of their Coronation…”

It recalled to me the ceremonies and sacraments of Baptism, and Communion etc. Not to use this as an argument against your comment, just to further explain my take on it. Again, thanks.

Hi Hank,

I’ve been reading through and through sonnet 125. As that is virtually the last ‘real’ one before the envoi, I think it has a great relevance. Somehow I can’t imagine that it’s no ABOUT Southampton, not TO Southampton. In my eyes it’s against Oxford’s nature to deal at this very place with the evil Cecil or even the almost-killer Elizabeth in this very last farewell sonnet. And I’ve found a biblical reference, which is at least interesting. It’s Ezekiel prophet:

“The spirit of the living creature was in the wheels.” – That is, the wheels were instinct with a vital spirit; the wheels were alive, they also were animals, or endued with animal life, as the creatures were that stood upon them. Here then is the chariot of Jehovah. There are four wheels, on each of which one of the compound animals stands; the four compound animals form the body of the chariot, their wings spread horizontally above, forming the canopy or covering of this chariot; on the top of which, or upon the extended wings of the four living creatures, was the throne, on which was the appearance of a man, ver. 26. ”

So in this part there’s canopy, and ‘compound’ – both can be found in sonnet 125. And there’s a reference to verse 26 (the magical sonnet-number), where:

“The pure oriental sapphire, a large well cut specimen of which is now before me, is one of the most beautiful and resplendent blues that can be conceived. I have sometimes seen the heavens assume this illustrious hue. The human form above this canopy is supposed to represent Him who, in the fullness of time, was manifested in the flesh. ”

So above the canopy is He, who’s adored, who’s manifested. Wouldn’t it be a great thing to bore the canopy? Not for the Queen, but for HIM.

Has this all any interest in it?

Thanks, Sandy. Not enough time to write now, except to say that since The Monument was published I have concluded that the “suborn’d informer” is Time itself — that which is all that is left for him to fight against — as in 123 — and in 124 he says Southampton or his royal blood is not subject to time — and here Time is accused of being a false accuser in future history — time is no longer the life of the queen, which has ended — and Southampton is the “true soul” — son of Oxford, Nothing truer than truth, and a soul or spirit. Time can no longer control him.

Thank you! It makes sense, really. But by all these you make it even stronger in my view that the canopy would be not above the Queen. Now I don’t have more time, either…

You have a good point, since the funeral is not just that of the Queen but also of the Tudor dynasty, which Southampton represents, so it is really a burial of his blood. Wow.

But Gentlemen, could Time in sonnets like 123-125 be Robert Cecil and no longer Elizabeth?

Yes, in this way: first, in 123 he very specifically tells Time: “Thy registers and thee I both defy,/ Not wond’ring at the present, nor the past,/ For thy records and what we see doth lie…”

So now with the passing of the Tudor dynasty, Time represents THE HISTORY OF THESE DAYS THAT IS NOW BEING WRITTEN AND THAT WILL BE WRITTEN IN THE FUTURE — and sure enough, Cecil is the chief writer of that [false or incomplete] history. So there is a combination.

In The Monument I have it that the Suborned Informer is Southampton, who will be forced to bear false witness against his own royal claim. But I think it’s Time and, yes, Cecil.

Thanks.

Why was the guy from Avon – the wool merchant chosen to represent Edward de Vere???

I’ve read your books and I’m thoroughly convinced that de Vere is the real author, BUT, now I want to know WHY the guy from Stratford was elected to represent such great works in literature???

Well, this is a very good question. First, there is some division over whether Oxford took his pen name from Pallas Athena, and the spear-shaking imagery, or from the Stratford man. I do not subscribe to the latter. I cannot even say that Shakspere of Stratford was a working actor and/or a Globe shareholder. I think not, but that’s my opinion. I believe there would have been some records at his family home in Stratford, or some kind of documentary information from London, other than the use of “Shakespeare” on cast lists and shareholder documents themselves. I believe that after the succession of James and the increased power of Robert Cecil, there began a process of trying to establish “Shakespeare” the author as an actor — to get him (in the public mind) out of the court, out of the nobility, and to remove his association with Southampton. They surely knew of Shakspere, of his similar (but hardly identical) name, and perhaps he was paid to stay dumb. In any case, his death in 1616 passed unnoticed. And in 1623, the folio, he is portrayed as an actor who wrote these plays — no poems, no sonnets, no Southampton. And even then the tilt to Stratford was so obscure that I can’t think too many readers if any would have had any idea of him. So the answer to your question, from my end, is that he was chose for the likeness of his name and also for his utter obscurity (and possible illiteracy as far as writing). It was in 1640, three years after Ben Jonson died, that Ben’s posthumous publisher John Benson (!) issued the Poems by Will Shakespeare Gent with the mixed-up sonnets and indicated, with the title of a separate poem, that Shakespeare died Anno 1616. If this was the plan, to unfold the legend in small increments over many years, it surely worked. But I hardly see Shaksper parading around as actor, much less as writer. Bottom line is that he was chosen precisely because he was such an unlikely candidate 🙂