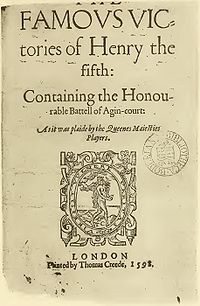

The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth, although not printed until 1598, was part of the wartime repertoire of the Queen’s Men in the 1580’s. Written by an obviously youthful (and anonymous) dramatist, the play also serves as a template or blueprint for the later Shakespearean trilogy 1 Henry IV, 2 Henry IV and Henry V.

Virtually everything in Famous Victories is repeated, in a refined and expanded form, in the Shakespeare plays printed in the latter 1590s. From that, traditional scholars conclude that Shakespeare was a shameless plagiarist. But isn’t it far more likely that the real “Shakespeare” wrote Famous Victories at a younger age, later re-working it to create his Henry trilogy?

Virtually everything in Famous Victories is repeated, in a refined and expanded form, in the Shakespeare plays printed in the latter 1590s. From that, traditional scholars conclude that Shakespeare was a shameless plagiarist. But isn’t it far more likely that the real “Shakespeare” wrote Famous Victories at a younger age, later re-working it to create his Henry trilogy?

Dr. Seymour Pitcher, a Stratfordian professor of English literature at the State University of New York, published a book in 1961 entitled The Case for Shakespeare’s Authorship of “The Famous Victories,” declaring that this youthful work “is not at all unworthy of Shakespeare as a spirited and genial apprentice dramatist.”

The play is “a clatter of events, its quick narrative interspersed with light and raucous comedy. Comical-historical it surely is, but, in its hybrid form, sufficiently self-consistent in tone. Sketchy and sometimes banal, it is gusty and flaunting. At best, it has poignancy in characterization and phrase. How else should we expect Shakespeare to have begun?”

The play is “a clatter of events, its quick narrative interspersed with light and raucous comedy. Comical-historical it surely is, but, in its hybrid form, sufficiently self-consistent in tone. Sketchy and sometimes banal, it is gusty and flaunting. At best, it has poignancy in characterization and phrase. How else should we expect Shakespeare to have begun?”

Dr. Pitcher suggests this must have been the Bard’s first play, written during his early twenties. Many Oxfordians would agree, although Ramon Jiminez has concluded that Edward de Vere may have written Famous Victories even earlier, in his teens.

Whatever the case, there is no evidence that Shakspere of Stratford could have penned Famous Victories in his twenties (or at any other time); but the young Earl of Oxford was uniquely qualified to have written it.

B.M. Ward concludes that Oxford wrote Famous Victories at age twenty-four in 1574. One reason is that the play comically refers to the involvement of Prince Hal (the future Henry V) in a robbery on Gad’s Hill, just a year after Oxford’s own men had been involved in such a robbery (or prank) in the very same place. Ward believes that the earl presented the play at court before Queen Elizabeth during the Christmas season of 1574.

“One can scarcely read The Famous Victories and not see in the skimpy little prose-play an early, comparatively amateurish exercise on the themes that would later come to magnificent flower in the Shakespearean dramas,” Charlton Ogburn Jr. writes, citing a speech in Famous Victories by the newly crowned Henry the Fifth in response to the belittling gift from the French Dauphin of tennis balls:

“One can scarcely read The Famous Victories and not see in the skimpy little prose-play an early, comparatively amateurish exercise on the themes that would later come to magnificent flower in the Shakespearean dramas,” Charlton Ogburn Jr. writes, citing a speech in Famous Victories by the newly crowned Henry the Fifth in response to the belittling gift from the French Dauphin of tennis balls:

“My Lord Prince Dauphin is very pleasant with me! But tell him instead of balls of leather we will toss him balls of brass and iron – yea, such balls as never were tossed in France…”

This same early material, reworked in the Shakespearean play Henry V, becomes a masterful speech by the king that begins:

We are glad the Dauphin is so pleasant with us:

His present and your pains we thank you for:

When we have match’d our rackets to these balls,

We will, in France, by God’s grace, play a set

Shall strike his father’s crown into the hazard… (1.2)

A prominent character in Famous Victories is Richard de Vere, 11th Earl of Oxford (1385-1417), but in 1 & 2 Henry IV and Henry V by “Shakespeare” that same earl disappears. Ogburn Jr. notes that this “initial inflation and later eradication of Oxford’s part” in the play is a telltale sign of something important. Once the author is viewed as de Vere, the explanation for Richard de Vere’s disappearance from the play is clear: to continue to give such prominence to an ancestor would jeopardize Edward de Vere’s anonymity.

Note: This Reason is now No. 40 in 100 Reasons Shake-speare was the Earl of Oxford, as edited by Alex McNeil.